ogc163

Superstar

A guest post by Adam Ozimek

I’ve written — and I still believe — that the rise of remote work triggered by the Covid pandemic will end up changing the way we produce things in the modern world. It has the potential to do for white-collar industries what electricity did for factory jobs — to distribute production to less costly places and allow more flexibility in job tasks. But for any of this to happen, remote work has to actually live up to the hype in terms of adoption.

So I asked my friend Adam Ozimek to write about the future of remote work, since he’s done plenty of research on the subject. Adam is the chief economist at the Economic Innovation group (a think tank whose founder I interviewed a year ago). Before that, he was an economist at Moody’s Analytics. He also co-wrote the popular econ blog Modeled Behavior, with Karl Smith. He tweets at @modeledbehavior.

The debate over remote work is evolving. We have gone from arguing about whether a significant level of remote working will be a permanent feature of the labor market to a greater focus on what the implications of that will be. Yet throughout this 2+ year debate, I think we have been consistently too pessimistic.

There are two reasons for more optimism. First, the thinking about who remote work is “leaving behind.” is far too narrow. Second, remote work opens up new frontiers for innovation and improved economic geography, and should spur bigger thinking by policymakers, pundits, and businesses, and more.

Before I begin making the case for why we should be more optimistic about remote work, we must first dig into what exactly it seems that remote work is doing so far.

In short, those with less education have less access to remote work jobs. The ability to work remotely is valued highly by some, with more than half of workers both saying that they place monetary value on it and also threatening to quit if forced back in the office. For those who value this way of working, working remotely represents a new direct benefit to higher skilled workers. Of course, for others who prefer to be in the office but are in an occupation where being fully remote proves optimal for firms, this will be a cost. But as a first approximation, I think this aspect of remote work does by itself increase inequality of outcomes.

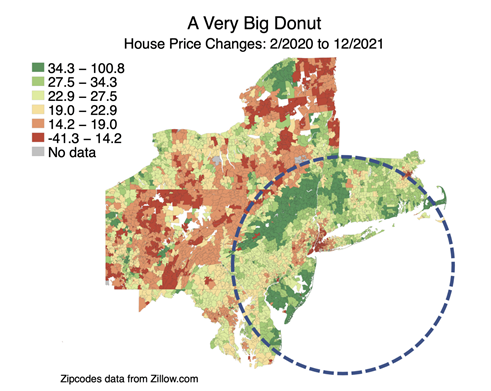

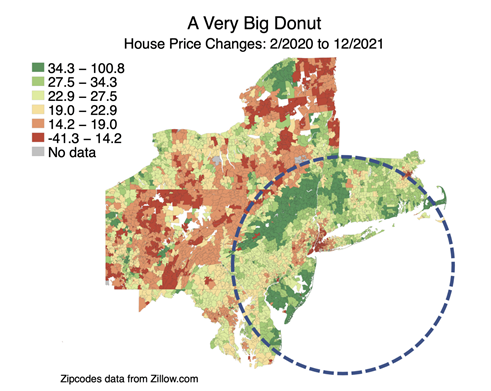

First, remote work pushed people out of city centers into nearby suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas within the same metro area. This is what Bloom and Ramani call “the donut effect, and quite a few papers have shown evidence of it at this point. For example Gupta, Mittal, and Peeters use Zip Code level data to show that being farther from a city center has become less negative for prices and rents post pandemic (shown below).

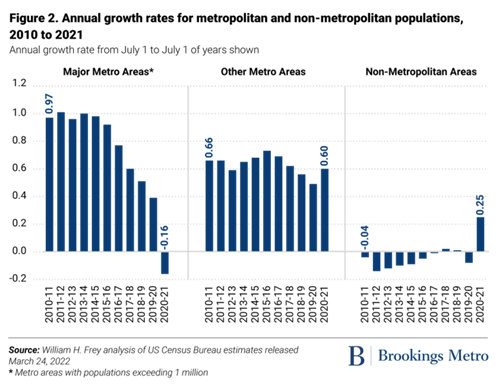

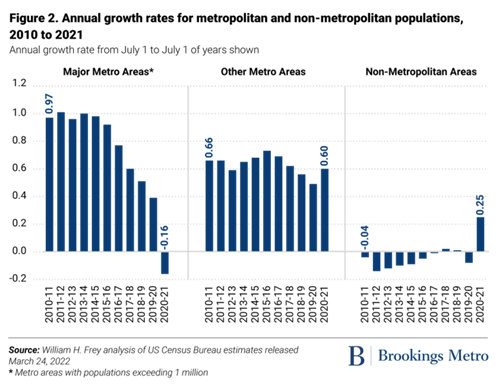

Second, it is not just that people are changing where they are living within MSAs, but also moving out of big expensive MSAs entirely. You can see this clearly below in house price data from Zillow at the zipcode level from a recent paper of mine, with a “donut effect” that extends not just within the NYC metro area, but well into northeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey. Looking at population data, Frey also showed that large urban metros have seen significant declines in population while non-metro areas have boomed.

So, yes, we have seen an urban exodus, both within metro areas and between them. But is remote work to blame? In a recent paper, I used regression analysis to see which factors best explain the change in county level population growth, comparing 2021 to pre-pandemic. I found bigger population losses in large urban areas with lots of occupations that could be done remotely, high housing costs, and where a large share of workers used to commute in. High housing costs and a supply of potential work-from-home jobs actually exacerbated each other, which is exactly what would be expected from remote work reducing the value of access to large, urban labor markets, and is consistent with remote work being an important demographic driver. (In technical terms, the interaction effect was significant, negative, and economically meaningful.)

This change should cause service workers to gradually follow the shifts in demand created by the new economic geography of remote work. One retort is that this will push lower skilled workers out of large urban areas, and this will be costly to them and leave them worse off. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that low-skilled workers in these places have been getting a bum deal over time anyway in terms of the economic return to living in superstar cities.

This story runs contrary to a lot of conventional wisdom, so it is worth digging into. It is true that one of the most important facts of economic geography used to be that lower skilled workers benefited from living in large urban areas where they could be surrounded by spillovers from more skilled workers. This theory was the crux of Moretti’s book The New Geography of Jobs. However, the evidence is accumulating that this spillover has changed over time.

Research from Autor first showed that while the high-skilled wage premium has continued to climb in more dense places, it has fallen for less skilled workers. This is what he calls “the falling ladder of urban opportunity.” But it’s even worse than it seems. Not only is the wage premium falling, but Card, Rothstein, and Yi argue that a significant share of the urban wage premium is due to those with unmeasured skills clustering there. So the wage premium is less than we thought, and it is also more due to worker sorting than actual increases in pay and productivity caused by the dense urban economy.

And folks, I hate to say it, but the story gets even worse from there. Because not only are low-skilled workers getting less of a pay bump than they used to, but urban NIMBYism means their housing expenses and cost of living have gone up significantly. Hoxie, Shoag, and Veuger go so far as to argue that once housing costs are taken into consideration, there is now an urban wage penalty for non-college workers. It’s not just housing either. Combining bank transaction data, scanner data, and much else, Moretti and Diamond look at broader consumption and find that expensive cities lead to less real consumption for less educated workers. While college-educated workers in expensive places earn a pay premium that is high enough to offset higher cost of living, the same is not true for low-skilled residents. Combining income and consumption effects, their results imply a high school dropout would experience a 26.9 percent increase in consumption from moving from the least to the most affordable commuting zone.

These stark results are a contrast to what was believed even a few years ago and also call into question whether consumer demand reallocation out of expensive cities is going to end up leaving workers worse off. In his work, Autor goes so far as to suggest exploring policies that “encouraging adults to seek work outside of those urban labor markets where the quality of jobs has not kept pace with the cost of living.” Remote work does exactly that, both for remote workers themselves but for those whose jobs their consumption supports.

In addition, the net costs to cities themselves should include positive impacts of greater competition. Many large cities have simply decided they don’t need to build enough housing, and have left affordability so poor and government services so unsatisfying that residents who no longer have to live there are rushing for the door. More competition is a good thing in the long-run, and residents and businesses feeling locked in by labor market access is not a recipe for good governance.

I’ve written — and I still believe — that the rise of remote work triggered by the Covid pandemic will end up changing the way we produce things in the modern world. It has the potential to do for white-collar industries what electricity did for factory jobs — to distribute production to less costly places and allow more flexibility in job tasks. But for any of this to happen, remote work has to actually live up to the hype in terms of adoption.

So I asked my friend Adam Ozimek to write about the future of remote work, since he’s done plenty of research on the subject. Adam is the chief economist at the Economic Innovation group (a think tank whose founder I interviewed a year ago). Before that, he was an economist at Moody’s Analytics. He also co-wrote the popular econ blog Modeled Behavior, with Karl Smith. He tweets at @modeledbehavior.

The debate over remote work is evolving. We have gone from arguing about whether a significant level of remote working will be a permanent feature of the labor market to a greater focus on what the implications of that will be. Yet throughout this 2+ year debate, I think we have been consistently too pessimistic.

There are two reasons for more optimism. First, the thinking about who remote work is “leaving behind.” is far too narrow. Second, remote work opens up new frontiers for innovation and improved economic geography, and should spur bigger thinking by policymakers, pundits, and businesses, and more.

Before I begin making the case for why we should be more optimistic about remote work, we must first dig into what exactly it seems that remote work is doing so far.

Remote work and inequality

Let’s start first with who remote work is directly benefiting, and who it is directly leaving behind. It is clear that not everyone can work remotely, and that working remotely is more common among the higher educated. Over the first year of the pandemic, 50 percent of those with a graduate degree were mostly working from home compared to only 10 percent of those with less with a high school degree. The education bias of remote work is consistent with pre-pandemic remote work patterns, and even which jobs can be done remotely in theory based on occupational characteristics.In short, those with less education have less access to remote work jobs. The ability to work remotely is valued highly by some, with more than half of workers both saying that they place monetary value on it and also threatening to quit if forced back in the office. For those who value this way of working, working remotely represents a new direct benefit to higher skilled workers. Of course, for others who prefer to be in the office but are in an occupation where being fully remote proves optimal for firms, this will be a cost. But as a first approximation, I think this aspect of remote work does by itself increase inequality of outcomes.

Spillovers from urban exodus

Another source of concern is that remote work has driven an exodus of people out of large urban areas, and this will leave urban service-sector workers worse off. It certainly seems true at this point that remote work has driven an exodus from large urban areas. There are really two reasons this is happening.First, remote work pushed people out of city centers into nearby suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas within the same metro area. This is what Bloom and Ramani call “the donut effect, and quite a few papers have shown evidence of it at this point. For example Gupta, Mittal, and Peeters use Zip Code level data to show that being farther from a city center has become less negative for prices and rents post pandemic (shown below).

Second, it is not just that people are changing where they are living within MSAs, but also moving out of big expensive MSAs entirely. You can see this clearly below in house price data from Zillow at the zipcode level from a recent paper of mine, with a “donut effect” that extends not just within the NYC metro area, but well into northeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey. Looking at population data, Frey also showed that large urban metros have seen significant declines in population while non-metro areas have boomed.

So, yes, we have seen an urban exodus, both within metro areas and between them. But is remote work to blame? In a recent paper, I used regression analysis to see which factors best explain the change in county level population growth, comparing 2021 to pre-pandemic. I found bigger population losses in large urban areas with lots of occupations that could be done remotely, high housing costs, and where a large share of workers used to commute in. High housing costs and a supply of potential work-from-home jobs actually exacerbated each other, which is exactly what would be expected from remote work reducing the value of access to large, urban labor markets, and is consistent with remote work being an important demographic driver. (In technical terms, the interaction effect was significant, negative, and economically meaningful.)

Isn’t this bad news?

What does the urban exodus mean for those economies? Barrero, Bloom, and Davis estimate that workers spending less time at the office will reduce expenditures in major city centers by 5 to 10 percent. And that doesn’t even include the decline in spending from people moving away from urban areas. That combination sounds like it will be bad news for service-sector workers in those areas. When combined with the direct inequality of remote work opportunity, it is easy to paint a pessimistic picture altogether. However, we have to widen our lens and look more broadly.The declining value of big city living

Something that is missed in this debate is that when remote workers (and their spending) reallocate themselves out of large urban areas, that creates new demand and new opportunities for service-sector workers in the places they move to. There is no reason to think that total spending will go down from remote work. Money saved from fewer lunches near the office will be spent on lunches or groceries closer to home. Yes, we should see retail and service sector demand decrease in urban cores and large urban areas like San Francisco and New York, but expand elsewhere.This change should cause service workers to gradually follow the shifts in demand created by the new economic geography of remote work. One retort is that this will push lower skilled workers out of large urban areas, and this will be costly to them and leave them worse off. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that low-skilled workers in these places have been getting a bum deal over time anyway in terms of the economic return to living in superstar cities.

This story runs contrary to a lot of conventional wisdom, so it is worth digging into. It is true that one of the most important facts of economic geography used to be that lower skilled workers benefited from living in large urban areas where they could be surrounded by spillovers from more skilled workers. This theory was the crux of Moretti’s book The New Geography of Jobs. However, the evidence is accumulating that this spillover has changed over time.

Research from Autor first showed that while the high-skilled wage premium has continued to climb in more dense places, it has fallen for less skilled workers. This is what he calls “the falling ladder of urban opportunity.” But it’s even worse than it seems. Not only is the wage premium falling, but Card, Rothstein, and Yi argue that a significant share of the urban wage premium is due to those with unmeasured skills clustering there. So the wage premium is less than we thought, and it is also more due to worker sorting than actual increases in pay and productivity caused by the dense urban economy.

And folks, I hate to say it, but the story gets even worse from there. Because not only are low-skilled workers getting less of a pay bump than they used to, but urban NIMBYism means their housing expenses and cost of living have gone up significantly. Hoxie, Shoag, and Veuger go so far as to argue that once housing costs are taken into consideration, there is now an urban wage penalty for non-college workers. It’s not just housing either. Combining bank transaction data, scanner data, and much else, Moretti and Diamond look at broader consumption and find that expensive cities lead to less real consumption for less educated workers. While college-educated workers in expensive places earn a pay premium that is high enough to offset higher cost of living, the same is not true for low-skilled residents. Combining income and consumption effects, their results imply a high school dropout would experience a 26.9 percent increase in consumption from moving from the least to the most affordable commuting zone.

These stark results are a contrast to what was believed even a few years ago and also call into question whether consumer demand reallocation out of expensive cities is going to end up leaving workers worse off. In his work, Autor goes so far as to suggest exploring policies that “encouraging adults to seek work outside of those urban labor markets where the quality of jobs has not kept pace with the cost of living.” Remote work does exactly that, both for remote workers themselves but for those whose jobs their consumption supports.

In addition, the net costs to cities themselves should include positive impacts of greater competition. Many large cities have simply decided they don’t need to build enough housing, and have left affordability so poor and government services so unsatisfying that residents who no longer have to live there are rushing for the door. More competition is a good thing in the long-run, and residents and businesses feeling locked in by labor market access is not a recipe for good governance.

Curious where did you hear that?

Curious where did you hear that?