88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

The U.S. Is Still a Long Way From Eliminating Food Insecurity

New data highlights the need to strenghten policies that ease access to a basic necessity.

Working-age people now make up the majority in U.S. households that rely on food stamps, a switch from a few years ago when children and the elderly were the main recipients. (AP Photo/Tamir Kalifa)

Food insecurity in America is an issue that can be hard to see. It is not synonymous with poverty: two-thirds of food-insecure households have incomes above the national poverty level, according to new data from The Hamilton Project. The same report also demonstrates that the way food insecurity is measured often masks the extent of the problem. Instances of food insecurity often arise suddenly and temporarily, and as a result are difficult to track from year to year.

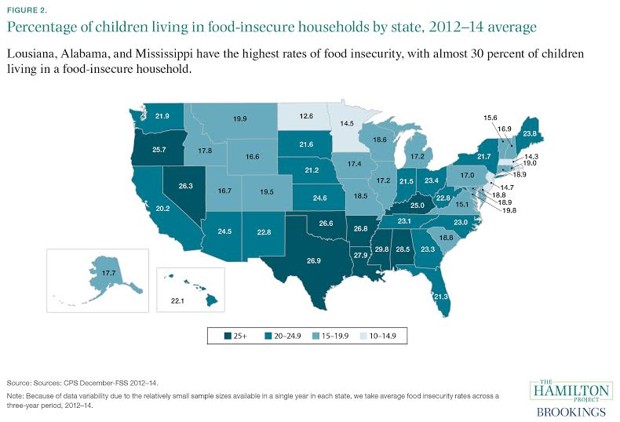

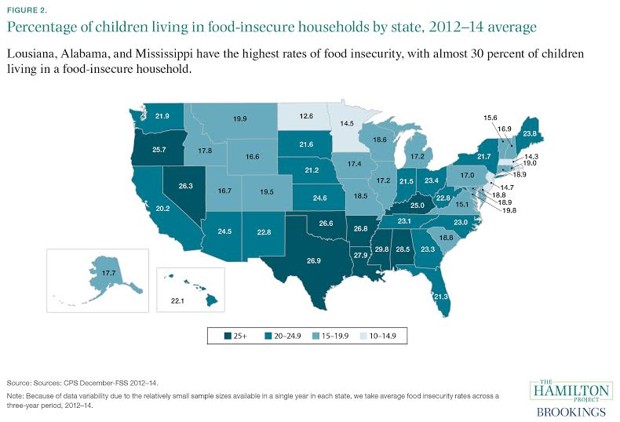

The share of children living in food-insecure households has not recovered since the recession, according to this infographic. (Courtesy of The Hamilton Project)

The report illustrates how rates of food insecurity increased across the U.S. after the recession in 2007, and have yet to come back down. This is especially obvious in households with at least one child. From 1998 to 2007, an average of 15.7 percent of households with children reported food insecurity. That number increased roughly four percentage points in 2008, and has maintained since. Employment rates have been on the rise in recent years, but the report concludes that there’s still a lag in economic stability. While 85 percent of food-insecure households with children are headed by at least one parent who works, the report explains:

Employment provides many benefits to households and children, yet working necessarily reduces the amount of time that an earner has available to do other tasks, including shopping for and preparing food. This time constraint may increase the monetary cost of food and, in turn, increase the likelihood that a family experiences food insecurity.

Since employment doesn’t always completely alleviate food insecurity, the report emphasizes the need for safety-net measures like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to be strengthened, and for outdated policies to be reassessed. An April 21st forum hosted by The Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution brought the U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack in conversation with Robert Greenstein, the president of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, to discuss potential policy solutions to food insecurity—and how to address the Surgeon General’s increasingly unlikely-seeming goal of eliminating food insecurity in children by the year 2020.

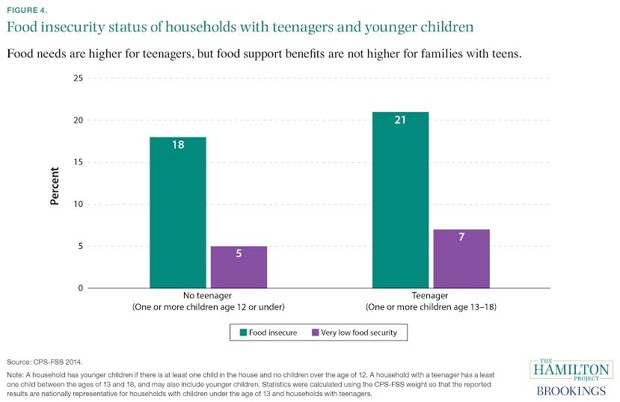

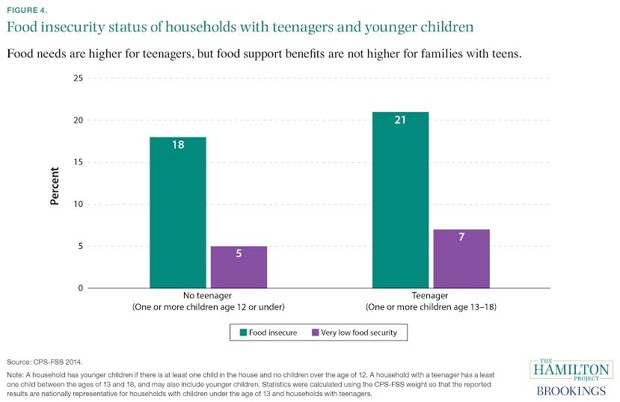

Food insecurity is highest among families with children, especially if those children are between the ages of 13 and 18. (Courtesy of The Hamilton Project)

Currently, the House of Representatives is moving to roll back the part of the Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act that provides universal free meals for schools with qualifyingly high rates of poverty. Called the Community Eligibility Provision, the 2010 policy goes a long way toward streamlining access to food and reducing stigma that affects young children and, disproportionately, teenagers, who are reliant on assistance programs. With the Reauthorization Act yet to be approved, the House is advocating to reduce the number of schools availing of the CEP by over 7,000—a move that, according to Vilsack, would harm a lot of low-income children and stagnate the elimination of food insecurity.

At the forum, Vilsack also spoke out against Paul Ryan’s proposal to administer SNAP and other benefits as part of block grants provided to states. This“Opportunity Grant” proposal, Vilsack said, offers no assurance that the money would be used to fight poverty and food insecurity over governors’ pet projects. That uncertainty, he said, is antithetical to the mission of SNAP, which is designed to be consistently available to those in need.

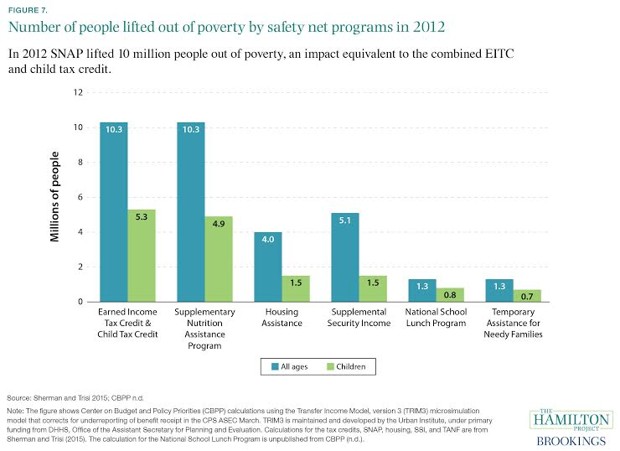

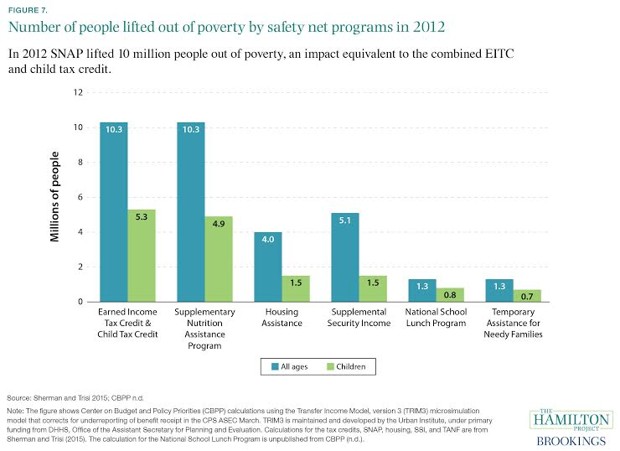

Among safety net programs, SNAP is one of the most effective in lifting people out of poverty. (Courtesy of The Hamilton Project)

Alongside the need to prevent these policy cuts, however, Greenstein asked a question: “What can we do to better communicate how much SNAP is improving people’s lives?” The Hamilton Project’s new data illustrates the efficacy of safety-net programs like SNAP in improving both individual lives and the economy overall. Still, a stigma against the program remains, despite the fact that 85 percent of beneficiaries are the elderly, people with permanent disabilities, children, and their parents. “Which one of those groups would you want to throw off the program?” Vilsack asked.

The answers to those questions look very different, depending on whether you’re asking advocacy organizations like The Hamilton Project and the CBPP, or Congress. And it’s the latter, says Diane Schanzenbach, one of the authors on the report, that’s providing the most substantial roadblock to alleviating food insecurity. The forum left her with the impression that “we know what we need to do, we think we know how to do it, but we’re in a place where we can’t get it done, because of Congress,” she tells CityLab. And there’s the matter of the election, leaving very little room for productive policy discussions in Washington. Which is exactly what will be required, Schanzenbach says, to “address this serious problem in the nation.”

The U.S. Is Still a Long Way From Eliminating Food Insecurity

New data highlights the need to strenghten policies that ease access to a basic necessity.

- EILLIE ANZILOTTI

- @eillieanzi

- Apr 22, 2016

- 1 Comment

Working-age people now make up the majority in U.S. households that rely on food stamps, a switch from a few years ago when children and the elderly were the main recipients. (AP Photo/Tamir Kalifa)

Food insecurity in America is an issue that can be hard to see. It is not synonymous with poverty: two-thirds of food-insecure households have incomes above the national poverty level, according to new data from The Hamilton Project. The same report also demonstrates that the way food insecurity is measured often masks the extent of the problem. Instances of food insecurity often arise suddenly and temporarily, and as a result are difficult to track from year to year.

The share of children living in food-insecure households has not recovered since the recession, according to this infographic. (Courtesy of The Hamilton Project)

The report illustrates how rates of food insecurity increased across the U.S. after the recession in 2007, and have yet to come back down. This is especially obvious in households with at least one child. From 1998 to 2007, an average of 15.7 percent of households with children reported food insecurity. That number increased roughly four percentage points in 2008, and has maintained since. Employment rates have been on the rise in recent years, but the report concludes that there’s still a lag in economic stability. While 85 percent of food-insecure households with children are headed by at least one parent who works, the report explains:

Employment provides many benefits to households and children, yet working necessarily reduces the amount of time that an earner has available to do other tasks, including shopping for and preparing food. This time constraint may increase the monetary cost of food and, in turn, increase the likelihood that a family experiences food insecurity.

Since employment doesn’t always completely alleviate food insecurity, the report emphasizes the need for safety-net measures like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to be strengthened, and for outdated policies to be reassessed. An April 21st forum hosted by The Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution brought the U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack in conversation with Robert Greenstein, the president of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, to discuss potential policy solutions to food insecurity—and how to address the Surgeon General’s increasingly unlikely-seeming goal of eliminating food insecurity in children by the year 2020.

Food insecurity is highest among families with children, especially if those children are between the ages of 13 and 18. (Courtesy of The Hamilton Project)

Currently, the House of Representatives is moving to roll back the part of the Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act that provides universal free meals for schools with qualifyingly high rates of poverty. Called the Community Eligibility Provision, the 2010 policy goes a long way toward streamlining access to food and reducing stigma that affects young children and, disproportionately, teenagers, who are reliant on assistance programs. With the Reauthorization Act yet to be approved, the House is advocating to reduce the number of schools availing of the CEP by over 7,000—a move that, according to Vilsack, would harm a lot of low-income children and stagnate the elimination of food insecurity.

At the forum, Vilsack also spoke out against Paul Ryan’s proposal to administer SNAP and other benefits as part of block grants provided to states. This“Opportunity Grant” proposal, Vilsack said, offers no assurance that the money would be used to fight poverty and food insecurity over governors’ pet projects. That uncertainty, he said, is antithetical to the mission of SNAP, which is designed to be consistently available to those in need.

Among safety net programs, SNAP is one of the most effective in lifting people out of poverty. (Courtesy of The Hamilton Project)

Alongside the need to prevent these policy cuts, however, Greenstein asked a question: “What can we do to better communicate how much SNAP is improving people’s lives?” The Hamilton Project’s new data illustrates the efficacy of safety-net programs like SNAP in improving both individual lives and the economy overall. Still, a stigma against the program remains, despite the fact that 85 percent of beneficiaries are the elderly, people with permanent disabilities, children, and their parents. “Which one of those groups would you want to throw off the program?” Vilsack asked.

The answers to those questions look very different, depending on whether you’re asking advocacy organizations like The Hamilton Project and the CBPP, or Congress. And it’s the latter, says Diane Schanzenbach, one of the authors on the report, that’s providing the most substantial roadblock to alleviating food insecurity. The forum left her with the impression that “we know what we need to do, we think we know how to do it, but we’re in a place where we can’t get it done, because of Congress,” she tells CityLab. And there’s the matter of the election, leaving very little room for productive policy discussions in Washington. Which is exactly what will be required, Schanzenbach says, to “address this serious problem in the nation.”

The U.S. Is Still a Long Way From Eliminating Food Insecurity