ogc163

Superstar

Matthias Doepke, PhD’00, and coauthor Fabrizio Zilibotti’s book Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids (Princeton University Press, 2019) takes a global and historical perspective on how parenting has been transformed in an economically unequal world. (Illustration by George Peters/istock.com)

For some parents, life is a rat race they want their children to win. For others, it’s a race they’ve already lost. Why macroeconomics plays a role.

Families are private worlds, operating in ways that can be hard to understand from the outside (and, often, the inside). And yet, itʼs the sum of these many intimate, mysterious spheres that makes the world we know.

This was one of the lessons Matthias Doepke took from Gary Becker, AMʼ53, PhDʼ55, as a UChicago PhD student. Becker helped him see that “what families do really has important macroeconomic implications,” says Doepke, PhDʼ00, now a professor at Northwestern University. Todayʼs economy stems from many personal choices about when or if to marry, how many children to have, and where to raise them and send them to school. The influence runs the other way too: economic factors shape our individual choices about parenting.

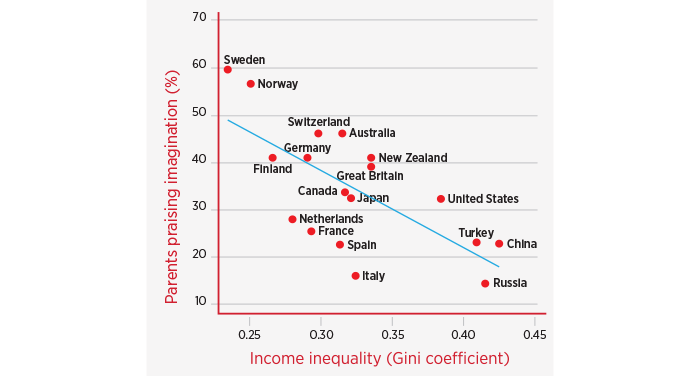

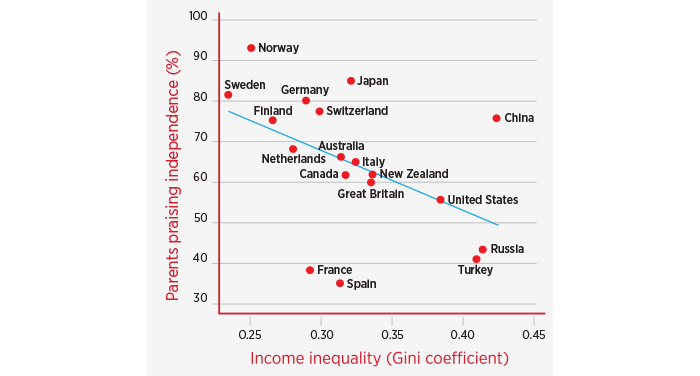

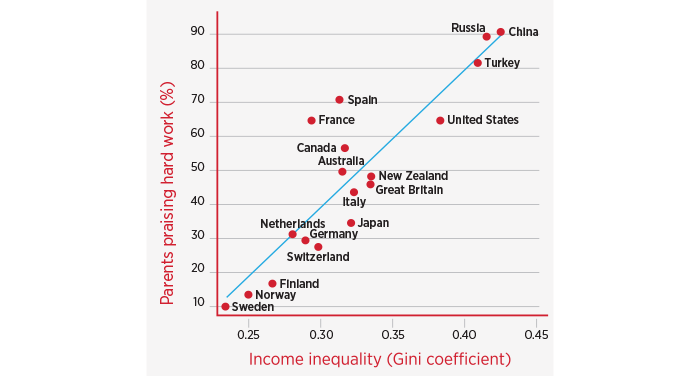

Thatʼs the argument of Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids (Princeton University Press, 2019), coauthored by Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti of Yale University. The book takes a global and historical perspective on how parenting has been transformed in an economically unequal world, where the divides are stark—both between wealthy and less wealthy nations, and within wealthy nations.

A central theme in Love, Money, and Parenting is the rise of so-called helicopter parenting in industrialized countries. Parents hover for a reason, Doepke and Zilibotti contend: in countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, and China, a comfortable life is increasingly hard to attain without a top-notch education, and even with one. While the turbocharged mode of parenting that has emerged in response is mostly the province of the middle class and up, it affects everyone fighting for a piece of the shrinking pie. Higher-income parents are anxious and lower-income parents are shut out.

Doepke and Zilibotti interweave quantitative data with their own experiences as children and parents. As Europeans now based in the United States (Doepke is German, and Zilibotti, who is Italian, has lived in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland), they have witnessed how child-rearing can differ over time and from place to place, a perspective that informs the book. Doepke considers himself a prime example of the changes he studies: despite loving his own low-key, unsupervised childhood, he has taken a far more hands-on approach to raising his three sons.

But he and Zilibotti see a common foundation underlying all parenting approaches, writing, “We believe that, broadly speaking, parents try their best to prepare their children for the society in which they will live.” In societies divided between haves and have-nots, using all the means they can to get ahead doesnʼt save some families from getting stranded.

“One thing thatʼs maybe both good and bad about economics ... is that we really like to generalize,” Doepke says, “because we have this view of people as being more or less all the same.”

When it comes to studying parenting, the economistʼs way of thinking has its pitfalls—clearly, there is no way to neatly classify the millions of daily interactions parents and children have, or to capture all the experiences that inform those interactions. But by generalizing, itʼs possible to compare times and places at scale, a practice of zooming out that “paints a clearer picture that is harder to see if you just focus on one particular time or place at a time,” Doepke argues.

To understand changes in parenting, Doepke and Zilibotti rely on the work of the late developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind, who in the 1960s developed an influential theory of parenting styles. These styles are defined by their levels of responsiveness (how communicative and attuned to their children they are) and demandingness (how much they monitor their children and set limits).

Authoritarian parents are characterized by high demandingness and low responsiveness (“eat your broccoli”), permissive parents by low demandingness and high responsiveness (“eat your broccoli if you want”), and authoritative parents by high demandingness and high responsiveness (“I want you to want to eat your broccoli”). Neglectful or uninvolved parents are neither responsive nor demanding. These styles differ in how much they ask of parents: Doepke and Zilibotti characterize authoritative and authoritarian parenting as more intensive, in that they require time, energy, and sustained focus.

Of course, parents arenʼt necessarily deliberate in their choices. “I donʼt think anybody, even economists, makes an Excel spreadsheet where they list the pros and cons of different parenting styles,” Doepke says. But, he argues, parents constantly if implicitly consider the future costs and benefits of their choices. Little Johnny may not want to study today, and you may not be in the mood to argue about it, but you believe heʼll suffer for not knowing his multiplication tables later. So, out come the flash cards.

Doepke uses his own case as an example: as a parent, he knows college admissions are important and competitive, and this ambient awareness makes him “a lot more anxious about academic outcomes than my own parents would have been.” As a result, heʼs become—without necessarily thinking about it—much more aware of and involved in his sonsʼ schoolwork than his parents were in his. An unconscious choice is still a choice.

For some parents, life is a rat race they want their children to win. For others, it’s a race they’ve already lost. Why macroeconomics plays a role.

Families are private worlds, operating in ways that can be hard to understand from the outside (and, often, the inside). And yet, itʼs the sum of these many intimate, mysterious spheres that makes the world we know.

This was one of the lessons Matthias Doepke took from Gary Becker, AMʼ53, PhDʼ55, as a UChicago PhD student. Becker helped him see that “what families do really has important macroeconomic implications,” says Doepke, PhDʼ00, now a professor at Northwestern University. Todayʼs economy stems from many personal choices about when or if to marry, how many children to have, and where to raise them and send them to school. The influence runs the other way too: economic factors shape our individual choices about parenting.

Thatʼs the argument of Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids (Princeton University Press, 2019), coauthored by Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti of Yale University. The book takes a global and historical perspective on how parenting has been transformed in an economically unequal world, where the divides are stark—both between wealthy and less wealthy nations, and within wealthy nations.

A central theme in Love, Money, and Parenting is the rise of so-called helicopter parenting in industrialized countries. Parents hover for a reason, Doepke and Zilibotti contend: in countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, and China, a comfortable life is increasingly hard to attain without a top-notch education, and even with one. While the turbocharged mode of parenting that has emerged in response is mostly the province of the middle class and up, it affects everyone fighting for a piece of the shrinking pie. Higher-income parents are anxious and lower-income parents are shut out.

Doepke and Zilibotti interweave quantitative data with their own experiences as children and parents. As Europeans now based in the United States (Doepke is German, and Zilibotti, who is Italian, has lived in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland), they have witnessed how child-rearing can differ over time and from place to place, a perspective that informs the book. Doepke considers himself a prime example of the changes he studies: despite loving his own low-key, unsupervised childhood, he has taken a far more hands-on approach to raising his three sons.

But he and Zilibotti see a common foundation underlying all parenting approaches, writing, “We believe that, broadly speaking, parents try their best to prepare their children for the society in which they will live.” In societies divided between haves and have-nots, using all the means they can to get ahead doesnʼt save some families from getting stranded.

“One thing thatʼs maybe both good and bad about economics ... is that we really like to generalize,” Doepke says, “because we have this view of people as being more or less all the same.”

When it comes to studying parenting, the economistʼs way of thinking has its pitfalls—clearly, there is no way to neatly classify the millions of daily interactions parents and children have, or to capture all the experiences that inform those interactions. But by generalizing, itʼs possible to compare times and places at scale, a practice of zooming out that “paints a clearer picture that is harder to see if you just focus on one particular time or place at a time,” Doepke argues.

To understand changes in parenting, Doepke and Zilibotti rely on the work of the late developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind, who in the 1960s developed an influential theory of parenting styles. These styles are defined by their levels of responsiveness (how communicative and attuned to their children they are) and demandingness (how much they monitor their children and set limits).

Authoritarian parents are characterized by high demandingness and low responsiveness (“eat your broccoli”), permissive parents by low demandingness and high responsiveness (“eat your broccoli if you want”), and authoritative parents by high demandingness and high responsiveness (“I want you to want to eat your broccoli”). Neglectful or uninvolved parents are neither responsive nor demanding. These styles differ in how much they ask of parents: Doepke and Zilibotti characterize authoritative and authoritarian parenting as more intensive, in that they require time, energy, and sustained focus.

Of course, parents arenʼt necessarily deliberate in their choices. “I donʼt think anybody, even economists, makes an Excel spreadsheet where they list the pros and cons of different parenting styles,” Doepke says. But, he argues, parents constantly if implicitly consider the future costs and benefits of their choices. Little Johnny may not want to study today, and you may not be in the mood to argue about it, but you believe heʼll suffer for not knowing his multiplication tables later. So, out come the flash cards.

Doepke uses his own case as an example: as a parent, he knows college admissions are important and competitive, and this ambient awareness makes him “a lot more anxious about academic outcomes than my own parents would have been.” As a result, heʼs become—without necessarily thinking about it—much more aware of and involved in his sonsʼ schoolwork than his parents were in his. An unconscious choice is still a choice.