mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

Bayard Rustin: The Panthers Couldn’t Save Us Then Either

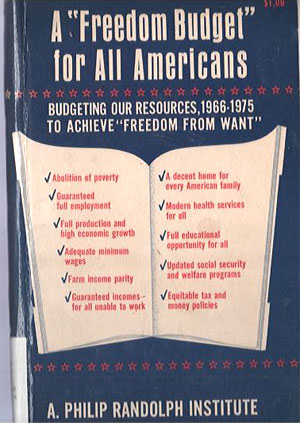

Rustin saw politics through a concrete, strategic lens, which provided a perspective that has become increasingly remote from both academic and activist experience. Indeed, as demonstrated in the essays selected here, he explicitly rejected the moralistic discourse that he saw undergirding much...

I think before I talk about the Freedom Budget it is necessary for us to make some analysis of where we are now, because everybody is writing great and long articles about prejudice and discrimination in the United States as if we were back in 1955 or ’56 or ’57 or ’50 or ’60 or ’62 or three or four. The fact is my friends—we are in a totally different period in the problem of civil rights than we have ever been in our history. And practically none of the experience of the past is particularly significant. …

Now I want you to know, in the present period we are dealing with practically no fundamental question in the minds of Negroes which are “Negro problems”—for what Negroes are interested in is decent housing, decent jobs, decent education and the right of participation in decision-making.

That perspective, which is attuned to concerns most black people experience as pressing in their daily lives and is sensitive to the significance of changing political environment, stands in sharp contrast to the race-reductionist tendency emerging then among militants within and on the fringes of the civil rights movement and certainly to Afropessimist and other contemporary race-reductionist twaddle now to the effect that black Americans—and, for Afropessimists, blacks all over the world and across time, always and forever—have faced most consequentially and been undone perpetually by an immutable, ethereal racism.4 Unlike Rustin’s matter-of-fact, real-time observation regarding the impact of the legislative victories, Black Power ideologues then and other race-reductionists since have rejected political analysis anchored by historical specificity in favor of an abstract idealism in which there is no meaningful or authentic political differentiation among black Americans, and race/racism exhausts the totality of black political life. Within that mindset, institutional politics—laws, Constitutional amendments, Supreme Court decisions, electoral successes, consolidation of power within national and local party apparatus, even a war to end slavery—is meaningless, only superficial window-dressing on the deeper Truth of eternal, indivisible black racial suffering. That is how, for example, Saidiya Hartman can dismiss Emancipation as a “nonevent.”5 And, as I and others have argued elsewhere, interpretive frames that homogenize black Americans’ political life into a singular, transhistorical struggle for an abstract racial justice—e.g., as a linear “black liberation struggle” or “black freedom movement”—drain actual politics from black political history and, most tellingly, obscure realities of conflict and interest differentiation among black people.

In fairness to Black Powerites, that race-reductionist viewpoint could seem more plausible on the cusp of the new political era than it should more than a half-century into its consolidation as normal life. The fact that race-first politics persists, and is arguably hegemonic, requires active denial of the realities of decades of history between then and now. After all, how do we account for all the black elected officials, upper-level public administrators, power brokers with and without portfolio, corporate executives, elite professors at elite universities, upper-class professionals, and truly rich (as opposed to that other kind of rich) black people and wannabes while contending that all black Americans suffer equally from racial oppression? Doing so requires the rhetorical equivalent of fastening hands over ears and bleating “Racial disparity! Racial disparity!” over and over as loudly as possible. William A. Darity, one of the most tireless proponents of reparations and racial wealth gap ideology, prefers focusing on the differences in mean “racial” wealth rather than differences in median “racial” wealth in part because the mean—the sum of all wealth held by people in each racial category divided by the number of wealth-holders in that category—yields a larger dollar figure as the measure of disparity. (Drawing from the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, Darity estimates the mean “racial” gap, between the supposedly average white and black household, as roughly $840,000; the median “racial” difference, the difference between the households at the mid-point of each racial distribution, was $164,100.) However, focus on the mean “racial” difference also obscures the possibly complicating fact that more than seventy percent of each “group’s” wealth is held by its richest ten percent.