The leading AI models are now very good historians

Three case studies with GPT-4o, o1, and Claude Sonnet 3.5, and what they mean

The leading AI models are now very good historians

Three case studies with GPT-4o, o1, and Claude Sonnet 3.5, and what they mean

Benjamin Breen

Jan 22, 2025

This is a post I began writing last year, but several things got in the way: above all, paternity leave. But also my own increasing dismay at the ways that LLMs were being used by students in the classroom. Ask anyone you know in education: ChatGPT has been a disaster when it comes to facilitating student cheating and — perhaps even more troubling — contributing to a general malaise among undergraduates. It’s not just that students are submitting entirely AI-written assignments. They are also (I suspect) relying on AI-generated answers far more comprehensively, not just in their homework but in their daily lives. This has a kind of flattening effect. I’m not alone in noticing the increasingly sameness of student responses to course material. LLMs, which are exquisitely well-tuned machines for finding the median viewpoint on a given issue, are surely contributing to it.

In other words, it’s clear that we will have a turbulent period of change as we figure out how to fit these new capabilities into our existing structures of education. For that reason, I’m not quite as optimistic about how this will go as I was when I wrote this back in fall of 2023:

How to use generative AI for historical research

Benjamin Breen

·

November 14, 2023

Last week, OpenAI announced what it calls “GPTs” — AI agents built on GPT-4 that can be given unique instructions and knowledge, allowing them to be customized for specific use cases.

Read full story

But that’s not the whole story. The headaches that LLMs have caused in the classroom are (I believe) more than counterbalanced by what they can offer as tools for research and self-directed learning. For this reason, I’m now even more optimistic about the long-term impact and utility of AI tools for historical research — and, by extension, for other forms of text or image-based research.

I’m told that OpenAI’s newish o1 model is genuinely helpful and creative when it comes to thinking through open problems in the sciences, especially fields like biology, physics, and medicine. It remains to be seen if it will facilitate any actual breakthroughs. But what’s clear to me is that both o1 and the older GPT-4o model are now almost shockingly good at several core historical skills, and that’s a good thing.

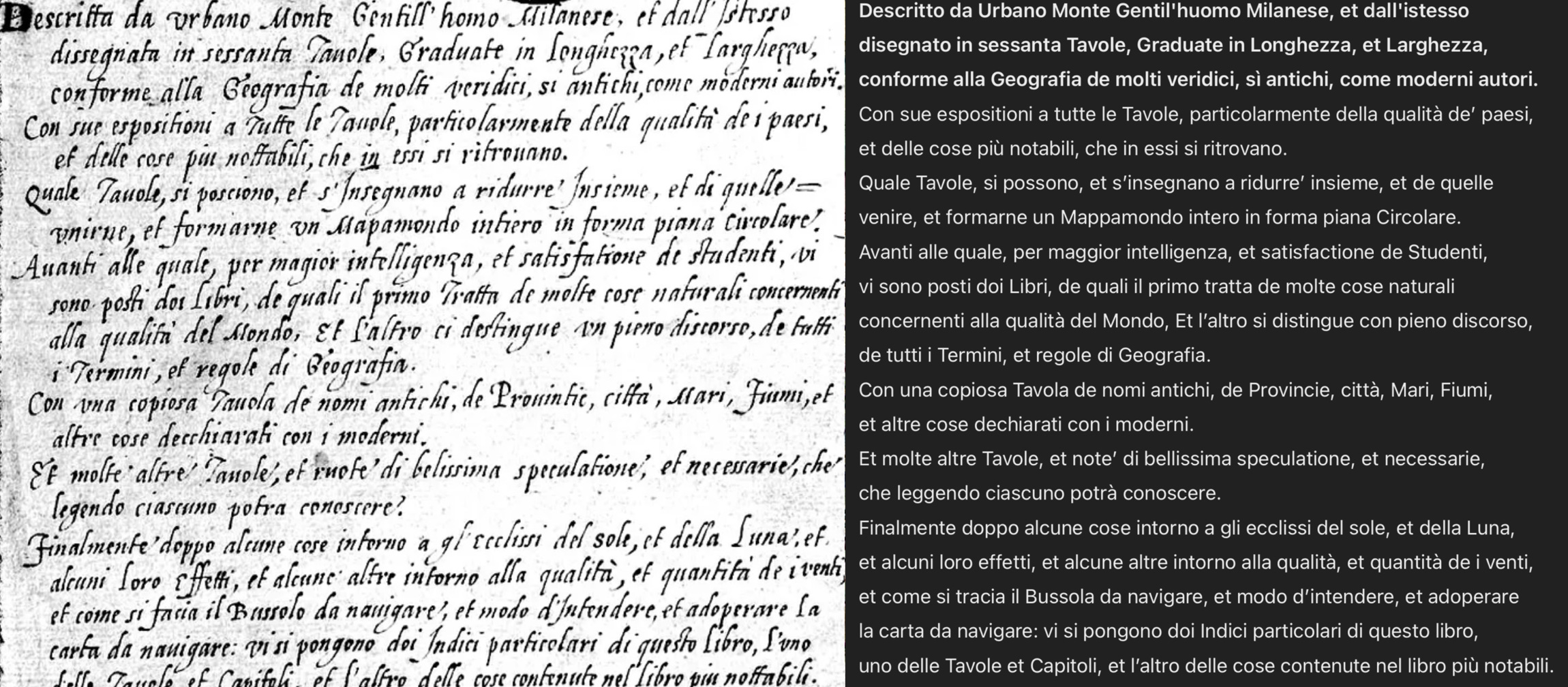

Case study #1: Transcribing and translating early modern Italian

Here, for instance, is how GPT-4o handles the task of transcribing this block of text from Urbano Monte’s world map, written in 16th century Italian cursive handwriting:

This is basically perfect, with the exception of a couple small errors (like “disegnato” instead of “dissegnata” in the second line).

Granted, Monte had unusually legible handwriting, but even “easy” early modern paleography like this is still the sort of thing that requires days or weeks of training to get the hang of.

Likewise, although my knowledge of Italian is not great, I can read it well enough to confirm that the translation it offers is good enough to use for research:

Described by Urbano Monte, a Milanese gentleman, and designed by himself

in sixty tables, graduated in length and width, according to the geography of many reliable authors, both ancient and modern.

With explanations for all the tables, particularly regarding the nature of the regions,

and the most notable things found within them. These tables can be combined and taught to form a complete world map in a circular flat form. Before these, for greater understanding and the satisfaction of students, there are two books: the first deals with many natural matters concerning the nature of the world, and the other is distinguished by a full discourse on all the terms and rules of geography.

It includes an extensive table of ancient names of provinces, cities, seas, rivers, and other elements clarified with their modern equivalents. And many other tables and notes of beautiful speculations and necessities, which anyone reading them will be able to understand. Finally, after some discussions on the eclipses of the sun and moon, and some of their effects, and other matters regarding the quality and quantity of the winds, as well as how to trace a navigational compass and how to understand and use a navigational chart, two detailed indices are provided in this book: one for the tables and chapters, and the other for the most notable contents of the book.

This was provided by a custom GPT I made, the Historian’s Friend, which is a variant of GPT-4o that has a system prompt with some specific directions relating to historical text transcription, analysis, etc. So when asked to provide “historical context” for a translation like this, it knows that it is supposed to cite only the most relevant academic sources.

An excerpt:

Early Modern Cartography and Cosmography

Themes: The creation of large-scale world maps in the early modern era reflects the integration of empirical observation, humanist scholarship, and the legacy of medieval cosmographical traditions. Urbano Monte’s emphasis on combining ancient and modern sources aligns with the Renaissance ideal of synthesizing classical wisdom with contemporary discoveries.

Notable Works for Context:

Brotton, Jerry. A History of the World in Twelve Maps (2012): Examines how maps from different periods reflect cultural and political ideologies.

Harley, J.B., and David Woodward. The History of Cartography (1987–2007): A multi-volume work exploring cartography’s development, including Renaissance mapmaking.

Renaissance Humanism and Classical Continuity

The text’s mention of “ancient and modern authors” reflects Renaissance humanism’s preoccupation with rediscovering and reconciling classical sources with contemporary knowledge.

Key Texts:

Grafton, Anthony. Defenders of the Text (1991): Investigates how Renaissance scholars revived classical knowledge through new methodologies.

Burke, Peter. The Renaissance Sense of the Past (1969): Examines how Renaissance scholars navigated the tension between reverence for antiquity and contemporary innovation.

… and so on.

The upshot: this is pretty much exactly what I would provide for a student trying to learn more on this topic, except it adds texts I should know about, but don’t (The Commerce of Cartography) and others which I hadn’t considered as being relevant to understanding a specific early modern map, but which, on reflection, actually are (the Peter Burke book on the Renaissance sense of the past).

Does this replace the actual reading required? Not at all. What it does is aggregate an expert-level knowledge of a topic. Even a year ago, when I requested further reading on a topic, ChatGPT would either invent fake sources or recommend terrible ones (like a History Channel website). That is no longer the case.

Case study #2: making sense of a strange 18th century medical text

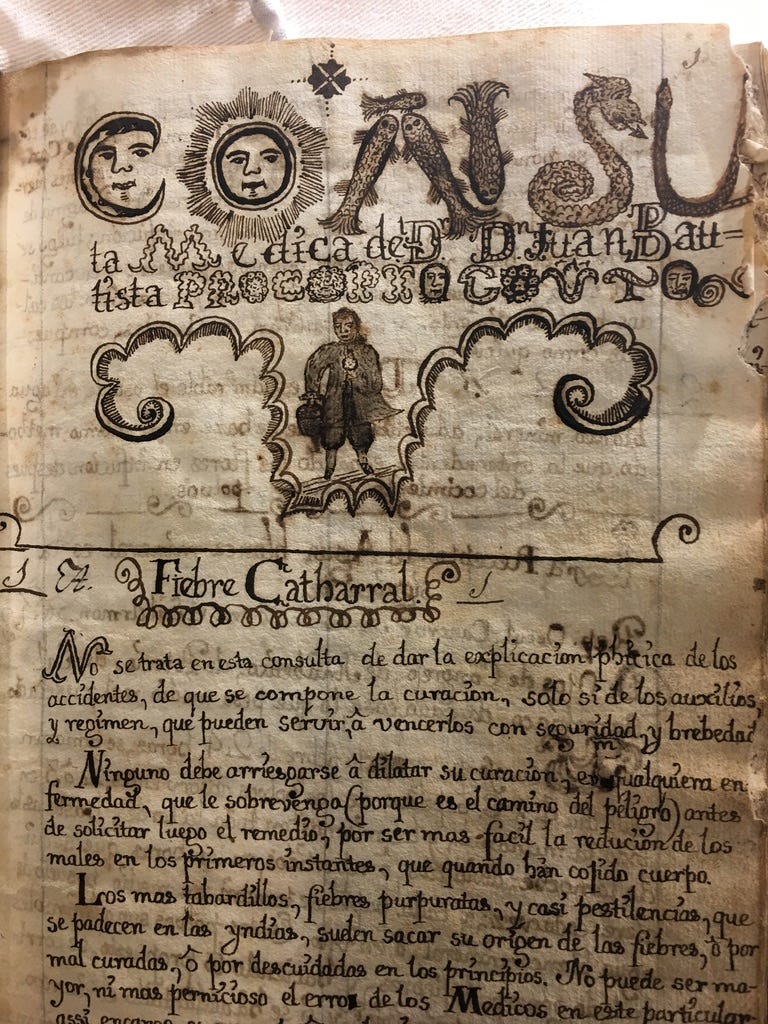

OpenAI’s o1 is the current reigning champ of AI models for reasoning and general-purpose thinking. In my testing, that has proven true when it comes to historical analysis, too. I picked a fairly readable but highly unusual historical source from 18th century Mexico to test it. The following image was provided with no context, just a request to transcribe, translate, and offer a detailed historical and iconographic analysis.

A page from an 18th century Mexican compendium of medical recipes. Credit: the Wellcome Library.

First off, how cool is this book? It’s a page from a manuscript of medical recipes written in 1770s Mexico and now held at the excellent Wellcome Library in London. This is my own photograph from a research trip, but the Wellcome has now fully digitized the book, which you can browse here.

Second, try reading the first lines. Can you make out the words?

o1 gave me the following as a transcription and translation:

Cons[ulta Médi]ca de D[on] Juan Batista Proco[p]io…

Section Title: “Fiebre Catharral”

No se trata en esta consulta de dar la explicación poética de los accidentes, de que se compone la curación, sólo sí de los auxilios, y régimen, que pueden servir a vencerlos con seguridad y brevedad. Ninguno debe arriesgarse a dilatar su curación, en cualquier enfermedad, que le sobrevenga (porque es el camino del peligro) antes de solicitar luego el remedio; por ser más fácil la reducción de los males en los primeros instantes, que cuando han cobrado cuerpo. Los más trabajadillos, fiebres purpurinas, y casi pestilenciales, que se padecen en las Yndias, suelen sacar su origen de las fiebres, y, por mal curadas, o por descuidadas en los principios. No puede ser mayor, ni más pernicioso el error de los Médicos en este particular …