JahFocus CS

Get It How You Get It

Full article

The Exotic Animal Traffickers of Ancient Rome

Thousands of bears, panthers, leopards, lions, and elephants were killed in the Colosseum—but how did they get there in the first place?

In what might be the world’s oldest recorded awkward situation, the Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero spent much of his term as Cilicia’s governor trying to ignore a very specific request from his former legal client Marcus Caelius Rufus. In several letters sent over the better part of a year, Caelius repeatedly begged Cicero to capture and send him a group of local leopards. He needed the animals, he explained, because he was trying to launch his political career—and nothing won over voters’ hearts better than live exotic animal hunts in the arena. Caelius’s opponent Curio had no trouble collecting exotic animals from his governor friends—why couldn’t Cicero spare a few of his local beasts?

As Cicero explained in a letter to another friend, Atticus, he simply wasn’t comfortable taking advantage of his position in this way: “I have said that it is inconsistent with my character that the people of Cibyra should hunt at the public expense while I am governor.”

Caelius wasn’t dissuaded, and his letters grew increasingly desperate. In one, he wrote, “It will be a disgrace to you if I have no Greek panthers.” In another, “In nearly every letter I have mentioned the subject of the panthers to you. It will be a disgrace to you that Patiscus has sent ten panthers to Curio, and that you should not send many times more.” These vague threats to his reputation clearly got under Cicero’s skin. His final response is cuttingly sarcastic.

About the leopards, the professional hunters are busy, acting on my orders. But there is an extraordinary scarcity of the beasts, and it is said that those leopards who are here complain bitterly that they are the only living creatures in my province against whom any harm is meditated.

Reluctant as Cicero was to round up wild beasts for Caelius’s benefit, bloody public spectacles featuring animals were already an important part of Roman culture. One type of wild animal show, known as damnatio ad bestias or execution by beasts, eventually became a trope of Christian martyr stories like that of Daniel and the lions.

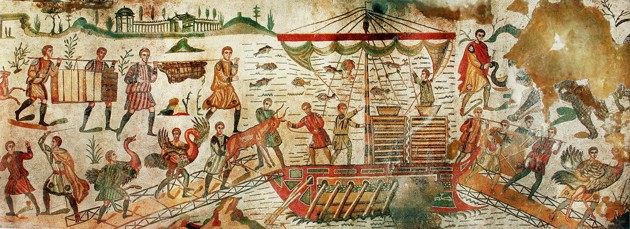

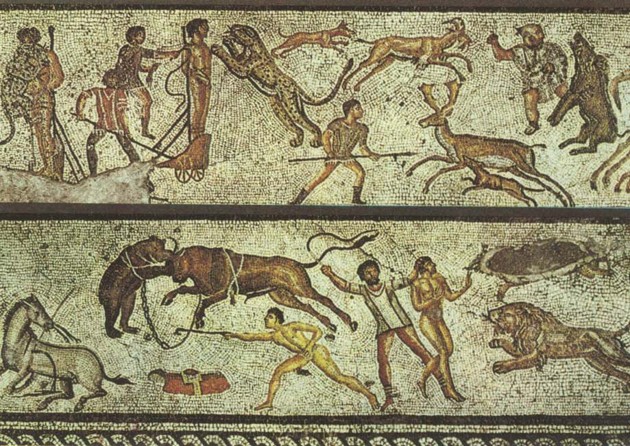

Tearing apart convicts made for quite a show, but it was not the only use Romans had for exotic animals. At least as popular were venationes, or “hunts,” a sport in which it was animals who were sentenced to death, whether at the hands of human hunters or in combat with other animals.

The venatio has survived into our day in the form of its direct descendant, Spanish bullfighting. Like modern bullfighting, the ancient venatio had its share of critics, including—not surprisingly given his reaction to the panther situation—Cicero, who thought the practice appealed to the worst parts of human nature. In a letter, the orator describes one venatio (organized by the famous general Pompey the Great) that was so brutal not even Rome’s typically bloodthirsty rabble could enjoy it.

The last day was that of the elephants, on which there was a great deal of astonishment on the part of the vulgar crowd, but no pleasure whatever. Nay, there was even a certain feeling of compassion aroused by it, and a kind of belief created that that animal has something in common with mankind.

The later writer Pliny the Elder describes the same sad spectacle.

When [the elephants] had lost all hope of escape, they tried to gain the compassion of the crowd by indescribable gestures of entreaty, deploring their fate with a sort of wailing, so much to the distress of the public that they forgot the general and his munificence carefully devised for their honour, and bursting into tears rose in a body and invoked curses on the head of Pompey.

Pompey’s elephant-hunt spectacle, which took place close to the end of the Roman Republic, provoked an emotional response from the crowds—but it by no means marked the end of venationes. In fact, over the course of the early Roman Empire, animal shows reached staggering new scales. In his autobiographical Res Gestae, Augustus claims that he had 3500 African animals killed in 26 venationesover the course of his reign. The better part of a century later, the emperor Titus inaugurated the Colosseum with a hundred days of spectacle in which 5000 wild beasts were killed. And in public games held from 108 to 109 C.E., the emperor Trajan arranged for 11,000 animals to fight in the arena.