Another new article:

http://kotaku.com/the-night-they-turned-on-the-first-nba-jam-machine-1797917964

The Night They Turned On The First NBA Jam Machine

Reyan Ali

Today 1:00pm

Filed to: NBA JAM

15.7K

357

Image:

VGMuseum

In this early excerpt from

NBA Jam, a book from Boss Fight Books and author

Reyan Ali coming in 2018, we learn about the night the development team from Midway let arcadegoers get their hands on their innovative, soon-to-be-legendary basketball game for the first time.

Boss Fight Books’ next “season” of

books about video games also features a

book about Final Fantasy V by Kotaku editor Chris Kohler, as well as volumes on the subjects of

Postal,

Knights of the Old Republic, and

Shovel Knight.

kotaku-bars");">

Somewhere along the maroon carpet, between the mirrored walls, among the rows of gleaming screens that lit the room, you could find it: a new arcade cabinet, debuting here tonight at Dennis’ Place For Games in Chicago, Illinois.

At six feet tall and 400 pounds, the device’s proportions resembled a big refrigerator. Its sides were emblazoned with a basketball’s pebbled orange pattern, the silhouetted logo of the National Basketball Association, and the word “Midway” in fire hydrant red italics. The cabinet housed coin slots, four control panels, speakers, and a 25-inch cathode ray tube monitor built to shine day and night. A marquee crowned the machine, announcing its title in all caps:

NBA JAM.

But on this early evening in late 1992, those letters sat unlit, the cabinet still unpowered. Customers entertained themselves with other attractions because the

Jam machine lacked an essential component: the memory chip containing the game’s code. That piece sat a few miles away at the offices of Williams Bally/Midway. A titan in coin-operated video and pinball, the company occupied a chunk of real estate on Chicago’s northwest side where it created its products from scratch, from the programming, marketing, and selling of the games to the construction and decoration of their metal-and-wood cases (or “cabinets”). Employees called the operation Williams. The world knew it as Midway.

After spending the past year programming and tweaking—

endlesslytweaking—their new take on the basketball video game, the

NBA Jam squad made extra last-minute adjustments. Once the code was good enough to go, they burned a fresh memory chip for the machine at Dennis’ Place.

Jam was about to move from the cloistered playground of development to the wilderness of public opinion.

When a coin-op game was almost complete, Midway sent a cabinet “on location” or “on test” to a local arcade to get an idea of how much it might make and how many cabinets it should assemble. Chicago had an abundance of spots for consumer feedback. Midway’s

Mortal Kombat had recently appeared at Times Square Arcade.

NBA Jam’s future lay in the hands of Dennis’ Place’s customers. All sorts came through the arcade doors: hardcore gamers and schoolchildren, teens and families, hipsters and gangsters alike.

Photo: leighty/

Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Tucked into a corner across the Belmont red line El stop, Dennis’ Place For Games boasted a large lightbulb-dotted sign. For its logo, a uniformed young man with a shock of neatly parted red hair stood stoically, probably posing for a military portrait. The visual was trustworthy and traditional—the kind of old-world insignia that could go on a bottle of aftershave or a jar of pasta sauce.

The man on the sign, in the name, and on its tokens was Dennis Georges. Born and raised in Greece, where he served in its navy, Georges dreamed of immigrating to America. He arrived in the 1960s and found his calling in the booming storefront video arcade business. In the late 1970s, he opened the first Dennis’ Place For Games in Chicago. He expanded it into multiple locations around the city, but this spot at 957 West Belmont Avenue was the

real one.

A black belt in karate and former pro boxer, the middle-aged Georges was friendly but no-nonsense when it came to the rules. His game room prohibited the following: smoking, drinking, eating, loitering, and wearing hats or head coverings. Because his arcade had been held up before, he suspended security cameras and mics from the ceiling. One time, Georges even kicked out

Defender creator Eugene Jarvis for banging on a game too hard.

Despite its touches of respectability, Dennis’ Place had a habit of being dirty. Its neighborhood was rough and heavily trafficked—once the center of a graffiti scene—but Dennis’ Place made a good spot for keeping kids off the streets as Chicago’s murder rate skyrocketed. Homeless youth would pack the room long past midnight, staying warm in the fluorescent glow.

VGMuseum

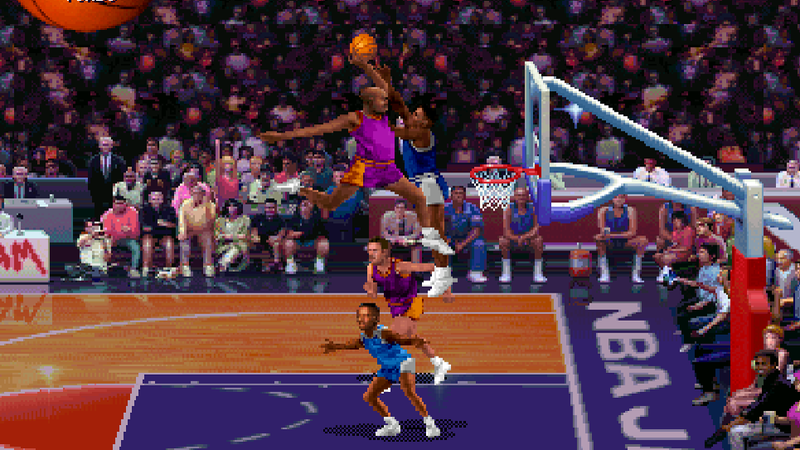

Before anyone could claim a turn, DiVita stood close so the machine could enter “attract mode.” A game’s attract mode was a polished demo sequence consisting of gameplay, high scores, character bios, logos, and other ephemera. When no one was paying to play, it became bait to catch passersby. Letting the attract mode run meant everyone at Dennis’ could get a first look at Midway’s handiwork together.

A virtual arena appeared, stuffed to the rafters with roaring fans. Two teams of two stood on the hardwood, ready to go. At center court, a referee blew his whistle and chucked a ball skyward. A disembodied voice piped up: “Here’s the tip!” Lifelike players galloped across the floor, passing, stealing, blocking, and trading points. The high-contrast colors of their jerseys popped like soda can labels.

VGMuseum

Shimmering atop the Greatest Players roster were the letters “MJT” for Mark Joseph Turmell. Six-foot-four and lanky, with long Robert Plant hair and a passion for mischief, the 29-year-old Turmell was

Jam’s mastermind. As a kid in suburban Michigan, he programmed Apple II games at home and mailed them off to a publisher in California. In return, he received $10,000 in monthly royalty checks before he was old enough to buy a pack of cigarettes.

After spending his twenties chasing fortune on the West Coast, he was back in the Midwest to work on the highest tech in video games: coin-op.

Smash T.V., his introduction to the arcade, performed well. Its semi-sequel,

Total Carnage, was a financial flop.

NBA Jam had not been without its troubles—the project almost never secured its crucial license—but Turmell believed he was onto something huge.

On the flickering screen, the attract mode ran a second roll call. This one was far more recognizable. Headshots and names of NBA stars flew by: Charles Barkley, Shawn Kemp, Hakeem Olajuwon, Scottie Pippen, Reggie Miller, Patrick Ewing, and dozens more. This was another revelation. No previous basketball video game had offered so many familiar NBA likenesses, especially ones that actually resembled the real deal.

VGMuseum

Hour after hour, crowds continued to huddle around

Jam. It would take a year for the team to understand just how massive of a phenomena they had birthed. Jurassic Park was 1993’s biggest movie, accumulating $346 million within a year. In that same timeframe,

NBA Jam tripled it to the tune of over $1 billion.

Gamers across the globe perfected

Jam techniques and mined for secrets. The game was splashed across magazine covers. It came to be adored by the public, the press, other developers, celebrities, and the real NBA players it sought to capture.

NBA Jam resulted in long-distance phone calls, short-distance road trips, and arguments over printer ink. Midway launched an entire division on its back.

When the game was adapted to home consoles—virtually every system available at the time—it blew up all over again. There were updates, sequels, spin-offs, and rip-offs.

NBA Jam commercials made it to TV and movie theater screens. A sprawling cast—politicians, musicians, sitcom stars, quarterbacks, sluggers, dinosaurs, and a parade of unknown programmers and executives—would be enshrined in those future incarnations. Its influence reverberated in hip-hop, fine art, sneakers, research papers, and real NBA games. It even led to bitter heartbreak for its creators who first witnessed it soar on Belmont Avenue.

But as the opening evenings on test wound down,

NBA Jam had not yet conquered the world. It was still a game with a broken feature that demanded an immediate fix.

After seeing the Stockton/Malone debacle, Turmell and DiVita left Dennis’ Place one night and circled back to work. Cutting past the dormant pinball tables and half-built arcade cabinets, they returned to their computers. Under the Utah Jazz’s player portraits on a menu screen, DiVita added tiny text and bars signifying attributes: “Speed,” “3 Ptrs,” “Dunks,” and “Def.” DiVita cranked up Malone’s dunking ability and rendered Stockton lightning fast. Now, they were a one-two punch, just like the real thing. The game’s sense of depth immediately increased.

This was a start. Within hours, it would be light again. Another full day at Midway lay ahead. They would be back in the arcade soon enough.

kotaku-bars");">

NBA Jam

will be available from Boss Fight Books in 2018. Y

MARK TURMELL

MARK TURMELL SAL DIVITA

SAL DIVITA MARK TURMELL

MARK TURMELL