get these nets

Veteran

===============================

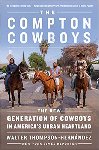

book is out now, based on the NYTimes article from 2018 and by the same author

(he is Blaxican)

=================================

For the Compton Cowboys, Horseback Riding Is a Legacy, and Protection

A group of childhood friends wants to create a safer community and challenge the notion that African-Americans can’t be cowboys.

Anthony Harris, 35, rides his horse through Compton, Calif.

By Walter Thompson-Hernández

- March 31, 2018

“They don’t pull us over or search us when we’re on the horses,” Mr. Harris said while riding a dark brown horse named Koda as two police cars slowly drove past him on a recent trip to the store. “They would have thought we were gangbangers and had guns or dope on us if we weren’t riding, but these horses protect us from all of that.”

The Compton Cowboys, composed of 10 friends who have known one another since childhood, but officially came together as a group in 2017, are on a mission to combat negative stereotypes about African-Americans and the city of Compton through horseback riding.

The tight-knit group first met more than 20 years ago as members of the Compton Jr. Posse, a nonprofit organization founded by Mayisha Akbar in Richland Farms, a semirural area in Compton that has been home to African-American horse riders since the mid-20th century. Like other nonprofits, the Compton Jr. Posse and the Compton Cowboys rely heavily on donations from alumni, government grants and local community support used to sustain the cost of the horses on the ranch.

Lamontre Hosley, 23, Leighton BeReal, 28, Randy Hook, 28, Kenneth Atkins, 26, and Carlton Hook, 28, at Richland Farms.

..

Most of the Compton Cowboys were first encouraged to join the organization by friends or relatives who believed horse riding would offer an alternative to gangs and violence prevalent throughout the city.

“When I was 11, I saw a black guy who was washing his horses outside of his home,” said Charles Harris, 29. “I walked up to him and started asking him questions about horses because I had only seen horses on TV before that.”

The man told him about the Compton Jr. Posse. The next day, Mr. Harris and his mother signed the papers and paid a fee to be a member.

Anthony Harris, 35, and Charles Harris, 29, practicing roping on the Richland Farms ranch.

For the Compton Cowboys, living in a community best known for the gangster rap group N.W.A. and high murder rates — 35 murders in 2016, with the crime index being nearly double the average in the United States, despite the fact that it has declined since 2002 — has been a motivating factor in their choices to ride horses.

“We’ve always wanted to give people a different side of Compton besides gangster rap and basketball,” said Leighton BeReal, 28, a member of the group who was born and raised in Compton.

Mr. BeReal, who like other members of the Compton Cowboys began riding in elementary school, found that using a horse as a method of transportation through Compton has also protected him from the threat of gang violence.

“If we’re walking on the street and a car drives past us that’s from a rival gang, they assume that we’re from a gang around here,” Mr. BeReal said, while riding alongside Mr. Harris and two other members of the group. “But if they see us on horses then they know we’re from Richland Farms and leave us alone.”

Mr. Harris tending to a horse at the ranch.

Maintaining the horses for casual riding and competitions at the Richland Farms property requires consistent maintenance and a collective effort from the Compton Cowboys. A typical workday for Anthony Harris — who is often joined by Mr. BeReal and Carlton Hook — begins at 5 a.m. with cleaning the stables and supplying the horses with fresh feed. Other members of the group like Roy-Keenan Abercrombia, 26, a full-time chef at a restaurant near Downtown Los Angeles, help at the ranch during their days off.

Carlton Hook, 28, on the Richland Farms property.

While work on the ranch may consist of strenuous physical labor, and occasional horse-related injuries, Anthony Harris uses his time working in the stables as an escape from the realities of a community that continues to struggle with gang violence.

“I was always around shootings and gangs, but none of that happens when I’m in the stables with the horses,” Mr. Harris said while restocking one of the stables with a fresh batch of hay. “There’s peace with the animals.”

(continued)