States With Large Black Populations Are Stingier With Government Benefits

States With Large Black Populations Are Stingier With Government Benefits

Research suggests that states with homogenous populations are more willing to spend on the safety net than those with higher shares of minorities.

Lyndon B. Johnson visits Tom Fletcher in Kentucky, as captured by a photographer from Time Magazine. Bettman / Getty

Poverty, in the 1960s, did not just affect white Appalachians like Fletcher. As Johnson himself wrote in his memoirs, the poor “were black and they were white, of every religion and background and national origin. And they were 35 million strong.” But Johnson chose a white family to represent poverty to the American public. His legislative agenda would be contentious, and he needed as much support from Republicans and Democrats as he could get. It seems he made a calculation: Convincing elected officials, the majority of whom were white, to help poor people would be a lot easier if they thought of the poor as white people like them.

The example highlights a fact of life about welfare in America: People are more likely to support anti-poverty programs if they conceive of the poor as “like them,” especially when it comes to race. On a state-by-state basis, places with the most homogeneous populations tend to be the most generous. Oregon, for example, one of the whitest states in the union, has an extensive safety net, as I’ve written about before. Today, Oregon, where 84 percent of the population is white and 1.8 percent of the population is black, gives a single-parent family of three $506 a month through Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF), the modern-day welfare program. Mississippi, which is 60 percent white and 38 percent black, gives a single-parent family of three just $170 a month. Oregon also helps people get off welfare by linking them to employment and pays their wages for up to six months. Mississippi has a work requirement for people receiving welfare, but does little to help them get a job. “I think what you see in other states is you see this kind of partisan, ‘we are going to take it out on poor people,’ philosophy. You just haven't seen that here,” Tina Kotek, a Democratic legislator in Oregon, told me last year.

That states have so much leeway in how they administer benefits is one of the legacies of a massive overhaul of welfare programs in 1996. In those reforms, spearheaded by then-president Bill Clinton, the government changed cash assistance to a program called TANF, which was administered through what are known as “block grants” to states. States could decide what they did with TANF funds, and could set their own limits for how much cash families could receive and who could receive it. A new Urban Institute analysis finds that allowing states to decide how to spend TANF dollars has led to even more racial discrepancies in who receives benefits. The Urban Institute analyzed a federal database that tracks state policy decisions about TANF and found that the states whose populations are more heavily African American are now less generous, more restrictive, and provide TANF for a shorter period of time than whiter states.

“Whenever you find space for discretion in the South and West, you often get racial discrimination as a result.”

This has big implications in today’s political climate, as Republicans talk about consolidating federal anti-poverty programs such as Medicaid and food stamps and sending them to states through block grants. Block-granting other programs could cause similar racial disparities in who receives them. “TANF is a cautionary tale about what block grants can mean,” said Heather Hahn, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and one of the authors of the study. “When states have flexibility to set policies, the state philosophies will prevail in determining what those policies are.”

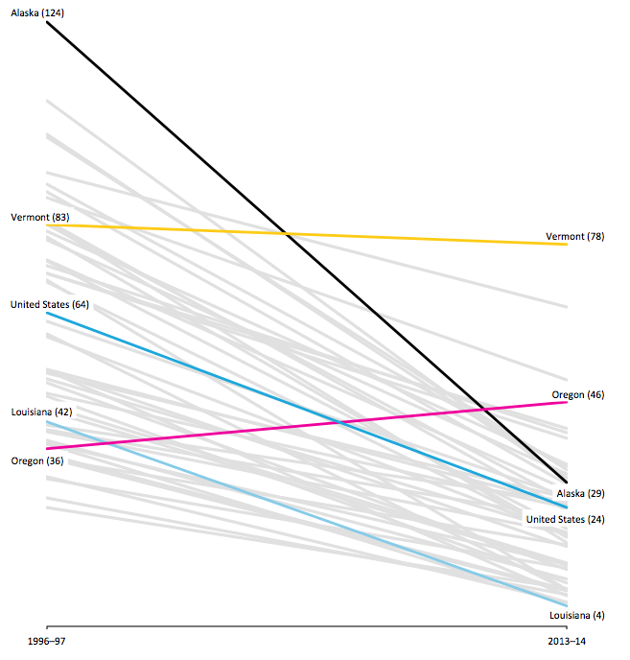

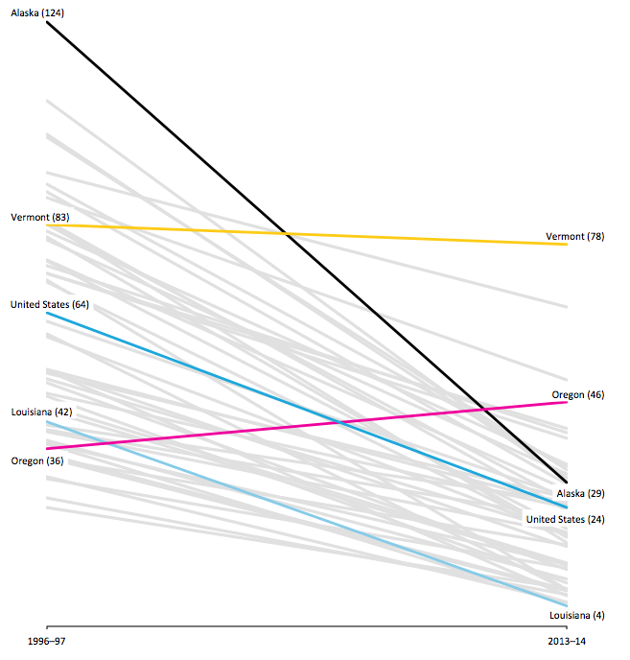

One way to track the generosity of state benefits is something called the TANF-to-poverty ratio. It measures how many families are receiving benefits for every 100 families living in poverty. The Urban Institute, using data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, found that the whitest states have the highest TANF-to-poverty ratio. They include Vermont, which gives TANF to 78 families for every 100 families in poverty, and Oregon, which gives TANF to 46 families for every 100 families living in poverty. States that have the lowest TANF-to-poverty ratio are those with high shares of African Americans, including Louisiana, which gives benefits to four families for every 100 living in poverty, and Arkansas, which gives benefits to seven families for every 100 living in poverty. (For more on Arkansas’ changes to welfare, read my story from 2016.) About 56 percent of the country’s African Americans live in the 25 states that rank lowest on the TANF-to-poverty ratio, the Urban Institute found, as opposed to 46 percent of white people.

A similar correlation was observed in measurements of the benefits’ generosity, according to the Urban Institute. A five-percentage-point increase in the African American share of the population was associated with an average decrease of $25 a month in the maximum monthly benefit available to families—$413 a month compared to $440 for the median state. States with higher shares of African Americans also have higher penalties when people don’t comply with a program’s rules, a policy known as “initial sanctions,” Hahn said. “When we look at some of these individual policies, we can see how having a higher share of African Americans in the population translate to a lower maximum benefit level, and harsher initial sanctions,” Hahn said. “When we put them all together and look across the board, we see this consistent pattern.”

It is not surprising that block-granting TANF has followed along racial divides: From the early history of the country’s welfare programs, allowing local discretion as to who can receive benefits has continually led to African American families receiving less or getting tossed off the rolls altogether. When mothers’ pensions, the precursor to welfare, were launched in the early 20th century, they mostly went to white women. Case workers had a fair amount of discretion in who received these pensions, and they believed African American women should work—something they tended to believe was beneath white women. They regularly denied African American women pensions, according to Jennifer Mittelstadt, a professor of history at Rutgers University.

When the Aid to Dependent Children program (which later became Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC) began in 1935, that discrimination persisted, according to Joe Soss, a professor at the University of Minnesota and the co-author of Disciplining the Poor: Neoliberal Paternalism and the Persistent Power of Race. Though ADC was a cash-assistance program for poor women, some states began disqualifying certain women from receiving it. In the South during harvest season, officials would shutter the welfare offices and require that African American women requesting ADC work in the fields, for instance. They’d enforce a series of rules designed to keep black women off welfare rolls, disqualifying women if they had a man living in their house who wasn’t their husband, or if their homes were deemed untidy by case workers, he said. “Whenever you find space for discretion in the South and West, you often get racial discrimination as a result,” Mittelstadt told me.

But as African Americans moved north, they were more successful at accessing benefits, helped in part by a welfare-rights movement tied to the Civil Rights movement. In addition, when the federal government began administering anti-poverty programs in the 1960s in the wake of Johnson’s War on Poverty, it became harder for states to deny aid, and the federal government challenged states that were discriminating against certain races. As a result, the number of African Americans on the welfare rolls started to climb.

Having more minorities on the rolls in turn created a new problem for case workers, though, who worried there would be backlash against welfare because of the number of black families receiving benefits, according to Mittelstadt. The term “welfare” had a positive connotation among Americans before the 1960s, according to Soss, but as the program became more diverse, stereotypes about “freeloaders” started to emerge. When case workers brainstormed about how to defend the program, they decided they could pitch welfare as something that would be “rehabilitative” for black women, rather than just a free handout. They would “rehabilitate” black women by making them work in order to receive benefits. “It’s a subtle rethinking of the purpose of the program,” Mittelstadt said. “That rethinking paves the way for the much bolder changes that came in the ‘70s and ‘80s and ‘90s.”

Indeed, reforms in the 1980s and 1990s added some work requirements for people who wanted to receive cash assistance. Still, because AFDC was a federal program, states did not have that much discretion in how they distributed benefits. The big change came in 1996, when the federal government restricted the amount of time that people could receive benefits, and required a certain percentage of welfare recipients to be working. The reforms of 1996 wiped away the victories of the welfare-rights era, and essentially allowed states to make receiving benefits much more difficult, according to Soss. “We really returned to a situation in which, although the money is coming from the federal government, the states have a great deal of discretion at least in the direction of limiting aid to people,” Soss told me.

As a result, many states have made it much more difficult to receive benefits. Out of 11,717 people in Mississippi who applied to get TANF last year, just 167 were approved, according to ThinkProgress. A bill recently passed in Mississippi may make it even harder to get benefits—it essentially privatizes the agency that approves benefits and asks potential recipients to jump through more hoops to apply. One of the lawmakers behind the bill penned an op-ed alleging that Mississippi welfare recipients were “taking advantage” of the program by living in multiple states, and speculating that enrollees were using stolen identities, and that some welfare recipients had actually won money in the lottery.

State-by-State Changes in the TANF-to-Poverty Ratio, 1996-2014

Source: The Urban Institute, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Blaming welfare recipients is a common strategy in states where recipients are a different race from almost all lawmakers and the majority of voters. Attitudes towards welfare recipients often dictate state policy. “If voters or policymakers perceive people receiving welfare as different from themselves, they may believe that welfare dependency is caused more by personal shortcomings than by circumstances beyond one’s control,” Hahn and her co-authors write.

In reality, most welfare recipients are people who were born into poverty, and who are struggling to find work and support their families. Changes to welfare in states with a higher share of African Americans have made this proposition more difficult. One woman I interviewed in Arkansas was struggling to support her family after her husband got shot. She wanted to look for jobs that were commensurate with her experience, but because the state of Arkansas required her to spend a certain number of hours volunteering per week in order to receive welfare, she barely had time to look for another job, or go on interviews. “The program is designed to keep you in a rut,” the woman, Raquel Williams, told me. “It’s not built to empower anybody.”

That policies can differ so much among different states—and that such differences correspond so tightly with racial breakdowns—is the unfortunate lesson of welfare reform. Giving states leeway on how they treat their poor has always been a risky proposition, with states with high shares of minorities historically choosing to leave people out. It’s only when the federal government intervenes that a more egalitarian response is possible. That, however, may not be what Congress wants.

States With Large Black Populations Are Stingier With Government Benefits

Research suggests that states with homogenous populations are more willing to spend on the safety net than those with higher shares of minorities.

Lyndon B. Johnson visits Tom Fletcher in Kentucky, as captured by a photographer from Time Magazine. Bettman / Getty

- Alana Semuels

- Jun 6, 2017

Poverty, in the 1960s, did not just affect white Appalachians like Fletcher. As Johnson himself wrote in his memoirs, the poor “were black and they were white, of every religion and background and national origin. And they were 35 million strong.” But Johnson chose a white family to represent poverty to the American public. His legislative agenda would be contentious, and he needed as much support from Republicans and Democrats as he could get. It seems he made a calculation: Convincing elected officials, the majority of whom were white, to help poor people would be a lot easier if they thought of the poor as white people like them.

The example highlights a fact of life about welfare in America: People are more likely to support anti-poverty programs if they conceive of the poor as “like them,” especially when it comes to race. On a state-by-state basis, places with the most homogeneous populations tend to be the most generous. Oregon, for example, one of the whitest states in the union, has an extensive safety net, as I’ve written about before. Today, Oregon, where 84 percent of the population is white and 1.8 percent of the population is black, gives a single-parent family of three $506 a month through Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF), the modern-day welfare program. Mississippi, which is 60 percent white and 38 percent black, gives a single-parent family of three just $170 a month. Oregon also helps people get off welfare by linking them to employment and pays their wages for up to six months. Mississippi has a work requirement for people receiving welfare, but does little to help them get a job. “I think what you see in other states is you see this kind of partisan, ‘we are going to take it out on poor people,’ philosophy. You just haven't seen that here,” Tina Kotek, a Democratic legislator in Oregon, told me last year.

That states have so much leeway in how they administer benefits is one of the legacies of a massive overhaul of welfare programs in 1996. In those reforms, spearheaded by then-president Bill Clinton, the government changed cash assistance to a program called TANF, which was administered through what are known as “block grants” to states. States could decide what they did with TANF funds, and could set their own limits for how much cash families could receive and who could receive it. A new Urban Institute analysis finds that allowing states to decide how to spend TANF dollars has led to even more racial discrepancies in who receives benefits. The Urban Institute analyzed a federal database that tracks state policy decisions about TANF and found that the states whose populations are more heavily African American are now less generous, more restrictive, and provide TANF for a shorter period of time than whiter states.

“Whenever you find space for discretion in the South and West, you often get racial discrimination as a result.”

This has big implications in today’s political climate, as Republicans talk about consolidating federal anti-poverty programs such as Medicaid and food stamps and sending them to states through block grants. Block-granting other programs could cause similar racial disparities in who receives them. “TANF is a cautionary tale about what block grants can mean,” said Heather Hahn, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and one of the authors of the study. “When states have flexibility to set policies, the state philosophies will prevail in determining what those policies are.”

One way to track the generosity of state benefits is something called the TANF-to-poverty ratio. It measures how many families are receiving benefits for every 100 families living in poverty. The Urban Institute, using data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, found that the whitest states have the highest TANF-to-poverty ratio. They include Vermont, which gives TANF to 78 families for every 100 families in poverty, and Oregon, which gives TANF to 46 families for every 100 families living in poverty. States that have the lowest TANF-to-poverty ratio are those with high shares of African Americans, including Louisiana, which gives benefits to four families for every 100 living in poverty, and Arkansas, which gives benefits to seven families for every 100 living in poverty. (For more on Arkansas’ changes to welfare, read my story from 2016.) About 56 percent of the country’s African Americans live in the 25 states that rank lowest on the TANF-to-poverty ratio, the Urban Institute found, as opposed to 46 percent of white people.

A similar correlation was observed in measurements of the benefits’ generosity, according to the Urban Institute. A five-percentage-point increase in the African American share of the population was associated with an average decrease of $25 a month in the maximum monthly benefit available to families—$413 a month compared to $440 for the median state. States with higher shares of African Americans also have higher penalties when people don’t comply with a program’s rules, a policy known as “initial sanctions,” Hahn said. “When we look at some of these individual policies, we can see how having a higher share of African Americans in the population translate to a lower maximum benefit level, and harsher initial sanctions,” Hahn said. “When we put them all together and look across the board, we see this consistent pattern.”

It is not surprising that block-granting TANF has followed along racial divides: From the early history of the country’s welfare programs, allowing local discretion as to who can receive benefits has continually led to African American families receiving less or getting tossed off the rolls altogether. When mothers’ pensions, the precursor to welfare, were launched in the early 20th century, they mostly went to white women. Case workers had a fair amount of discretion in who received these pensions, and they believed African American women should work—something they tended to believe was beneath white women. They regularly denied African American women pensions, according to Jennifer Mittelstadt, a professor of history at Rutgers University.

When the Aid to Dependent Children program (which later became Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC) began in 1935, that discrimination persisted, according to Joe Soss, a professor at the University of Minnesota and the co-author of Disciplining the Poor: Neoliberal Paternalism and the Persistent Power of Race. Though ADC was a cash-assistance program for poor women, some states began disqualifying certain women from receiving it. In the South during harvest season, officials would shutter the welfare offices and require that African American women requesting ADC work in the fields, for instance. They’d enforce a series of rules designed to keep black women off welfare rolls, disqualifying women if they had a man living in their house who wasn’t their husband, or if their homes were deemed untidy by case workers, he said. “Whenever you find space for discretion in the South and West, you often get racial discrimination as a result,” Mittelstadt told me.

But as African Americans moved north, they were more successful at accessing benefits, helped in part by a welfare-rights movement tied to the Civil Rights movement. In addition, when the federal government began administering anti-poverty programs in the 1960s in the wake of Johnson’s War on Poverty, it became harder for states to deny aid, and the federal government challenged states that were discriminating against certain races. As a result, the number of African Americans on the welfare rolls started to climb.

Having more minorities on the rolls in turn created a new problem for case workers, though, who worried there would be backlash against welfare because of the number of black families receiving benefits, according to Mittelstadt. The term “welfare” had a positive connotation among Americans before the 1960s, according to Soss, but as the program became more diverse, stereotypes about “freeloaders” started to emerge. When case workers brainstormed about how to defend the program, they decided they could pitch welfare as something that would be “rehabilitative” for black women, rather than just a free handout. They would “rehabilitate” black women by making them work in order to receive benefits. “It’s a subtle rethinking of the purpose of the program,” Mittelstadt said. “That rethinking paves the way for the much bolder changes that came in the ‘70s and ‘80s and ‘90s.”

Indeed, reforms in the 1980s and 1990s added some work requirements for people who wanted to receive cash assistance. Still, because AFDC was a federal program, states did not have that much discretion in how they distributed benefits. The big change came in 1996, when the federal government restricted the amount of time that people could receive benefits, and required a certain percentage of welfare recipients to be working. The reforms of 1996 wiped away the victories of the welfare-rights era, and essentially allowed states to make receiving benefits much more difficult, according to Soss. “We really returned to a situation in which, although the money is coming from the federal government, the states have a great deal of discretion at least in the direction of limiting aid to people,” Soss told me.

As a result, many states have made it much more difficult to receive benefits. Out of 11,717 people in Mississippi who applied to get TANF last year, just 167 were approved, according to ThinkProgress. A bill recently passed in Mississippi may make it even harder to get benefits—it essentially privatizes the agency that approves benefits and asks potential recipients to jump through more hoops to apply. One of the lawmakers behind the bill penned an op-ed alleging that Mississippi welfare recipients were “taking advantage” of the program by living in multiple states, and speculating that enrollees were using stolen identities, and that some welfare recipients had actually won money in the lottery.

State-by-State Changes in the TANF-to-Poverty Ratio, 1996-2014

Source: The Urban Institute, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Blaming welfare recipients is a common strategy in states where recipients are a different race from almost all lawmakers and the majority of voters. Attitudes towards welfare recipients often dictate state policy. “If voters or policymakers perceive people receiving welfare as different from themselves, they may believe that welfare dependency is caused more by personal shortcomings than by circumstances beyond one’s control,” Hahn and her co-authors write.

In reality, most welfare recipients are people who were born into poverty, and who are struggling to find work and support their families. Changes to welfare in states with a higher share of African Americans have made this proposition more difficult. One woman I interviewed in Arkansas was struggling to support her family after her husband got shot. She wanted to look for jobs that were commensurate with her experience, but because the state of Arkansas required her to spend a certain number of hours volunteering per week in order to receive welfare, she barely had time to look for another job, or go on interviews. “The program is designed to keep you in a rut,” the woman, Raquel Williams, told me. “It’s not built to empower anybody.”

That policies can differ so much among different states—and that such differences correspond so tightly with racial breakdowns—is the unfortunate lesson of welfare reform. Giving states leeway on how they treat their poor has always been a risky proposition, with states with high shares of minorities historically choosing to leave people out. It’s only when the federal government intervenes that a more egalitarian response is possible. That, however, may not be what Congress wants.