Staring down the wrecking ball, these Brooklyn grandmothers won’t be moved

A Crown Heights building in limbo could inspire more landlords to deregulate through demolition—or more tenants to fight to stay in their homes.

Staring down the wrecking ball, these Brooklyn grandmothers won’t be moved

A Crown Heights building in limbo could inspire more landlords to deregulate through demolition—or more tenants to fight to stay in their homes.

APR 10, 2024By Emma Whitford, City Limits

(Adi Talwar) Alema Finnigan, Pamela Hicken and Rosalee Frater stand outside the entrance of 285 Eastern Parkway in March 2024.

Rosalee Frater understands the economic forces she’s up against. The things she loves about her neighborhood, that the 61-year-old mother of five has known since she was a teenager, have helped solidify its status today as what she calls a “pot of gold.”

Frater’s rent stabilized apartment at 285 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights is half a block from the subway. The Brooklyn Museum and stately Central Library are a few blocks west, and she can easily walk to Prospect Park.

So when she and her family started receiving buyout offers from their landlord Renaissance Realty Group in late 2019, they declined. Frater’s mother Alema Finnigan, who lives downstairs, also refused to leave, as did two other senior women, Pamela Hicken and Jean Thompson. At the time, they had all been neighbors for over 40 years.

Today, their four-story building is nearly empty. Thompson moved out abruptly in January, leaving just three apartments rented. But by standing their ground, the remaining tenants are delaying their landlord’s application to knock the building down, along with adjoining 291 Eastern Parkway—a combined 33 apartments.

Renaissance has filed plans for an eight-story building on the site, with 76 units, a healthcare facility, and 40-car garage. They claim this would be a net gain for the neighborhood in the midst of a historic housing shortage. But pursuing demolition is also one of the few legal pathways to remove an entire building from rent regulation.

Now this familiar story—a tenant’s home is a landlord’s financial asset—has a new character. In 2015 Renaissance took out a $5.5 million mortgage from Signature Bank. After the bank collapsed spectacularly in 2023, the loan passed to a federally-backed joint venture with a mission to preserve affordable housing.

Homes and Community Renewal (HCR), the state agency that oversees regulated housing, has yet to say if Renaissance can proceed with evicting the remaining tenants at 285 Eastern Parkway, a prerequisite to demolition. If, or how, the new lender will exert pressure isn’t yet clear.

But Frater’s plan is. “My thing is stand firm, hold your ground, because that’s where you live at,” she told City Limits on a warm evening in October. “And if you don’t fight for you, who’s going to fight for you? No one. You got to stand up to the end.”

As news geared toward Black Americans shrinks, newsletters like this work to inform our community. If you think this work is important, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Sharing the newsletter with others helps it grow, too!

Subscribe

How to deregulate a building

Rent stabilization has allowed Frater and her neighbors to live affordably for decades, as their neighborhood has changed dramatically. Crown Heights North saw its Black population drop 20 percent over the decade ending in 2020, from a majority to a plurality, while its white population nearly doubled. Rents have soared.The neighborhood’s median asking rent was $3,000 in February, according to Streeteasy. The holdout 285 Eastern Parkway tenants, by contrast, pay between $516 and $810 a month, thanks to limited allowable rent increases. But even their own building has been in a state of transformation for years.

Before the 2019 passage of the state’s Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act (HSTPA), landlords could remove apartments from stabilization by churning through tenants. Vacancies came with a tantalizing 20 percent rent boost. By renovating, sometimes fudging the math, landlords could push them even higher.

Exactly when, and how, Renaissance deregulated most of 285 and 291 Eastern Parkway isn’t clear. In April 2022, tenants found a listing for one apartment touting a “Gorgeous NEW Kitchen.” Other empty units appear fresh and clean, even as issues in the occupied ones, like sagging floors and damaged ceilings, go unfixed.

But the building also underwent major renovations years ago. Lashawn Diallo, one of Frater’s daughters, recalls some tenants taking buyouts in the late aughts. The city approved renovation plans for 291 Eastern Parkway starting in 2006, and over half of 285 a few years later. A 2013 sales pitch called the property 75 percent “free market.”

(Adi Talwar) Rosalee Frater in her apartment at 285 Eastern Parkway in early October 2023.

By December 2019, when Renaissance agent Michael Schultz approached Frater and her husband with an initial $149,000 offer, stabilized tenants remained in just seven of the apartments on her side of the building. Two accepted buyouts by June 2022, and another tried to take over her late grandmother’s lease, only to be evicted last summer.

The trajectory on the other side of the building is more hazy, but Renaissance described it as entirely vacant in an October 2022 ledger. A few people appear to be living there today, though Frater, Hicken and Finnigan believe they are affiliated with the landlord.

Diallo, who is currently living in her parents’ apartment with her teenage daughter, believes that Renaissance never anticipated that a few tenants would refuse to move. “That was a wildcard,” she said.

Hicken says she had a clarifying experience in early 2021 when Schultz, of Renaissance, asked her to encourage others to take the money and leave.

“They probably figured with my mouth and my pull, I could talk to the other tenants,” she recalled. But she refused what she saw as a betrayal to her friends. Instead, she called local Assemblymember Phara Souffrant Forrest, who was a member of the Crown Heights Tenant Union before taking office.

Forrest says that she sees her role as helping tenants organize, as “that’s the source of our power.” Her staff began hosting meetings on the 285 side of the building in May 2021, with a mix of old-timers and newer tenants, even as it was emptying out. The latter, living in unregulated apartments, didn’t have any rights to a lease renewal.

The demolition factor

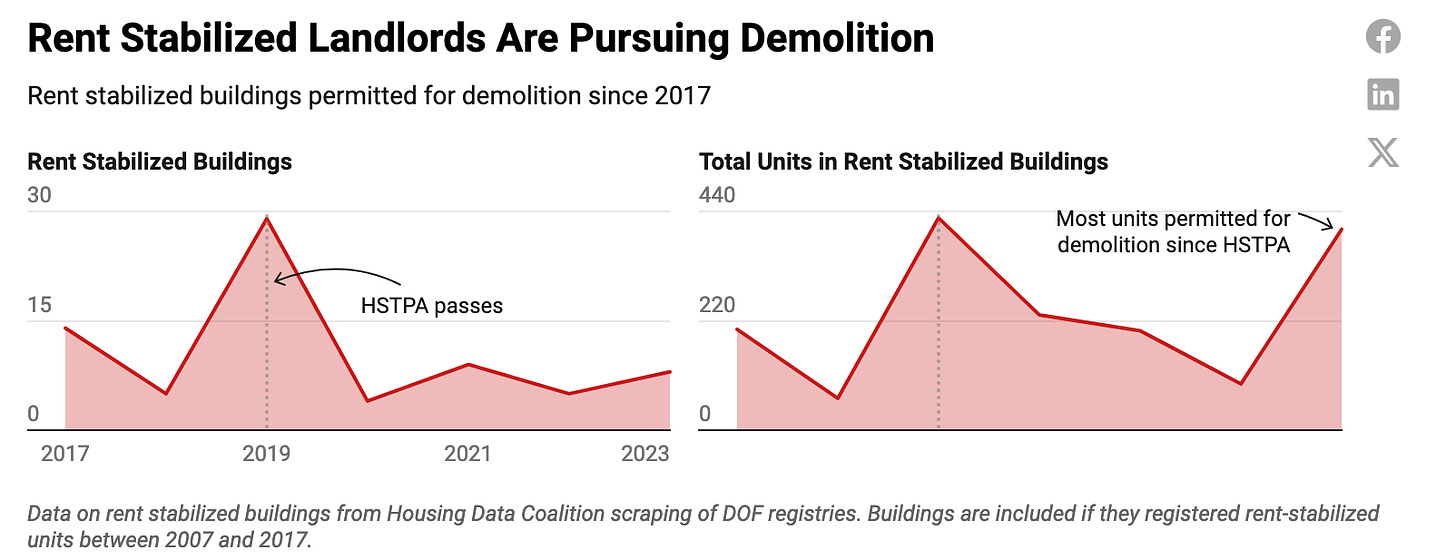

Today, demolition is one of the only ways to definitively wipe out a building’s regulated status. The 2019 rent laws narrowed the path for co-op and condominium conversion, and increased scrutiny on the “substantial rehabilitation” route, which requires replacing most of a building’s systems.The New York City Department of Buildings issued eight demolition permits for buildings with stabilized apartments in 2023, a City Limits analysis found. Last year’s permits cover about 400 units, according to counts from Department of Finance tax bills—the most since the passage of the HSTPA, though still trailing the early 2010s.

Chart: Patrick Spauster | City LimitsSource: DOB and DOF. Get the data. Created with Datawrapper.

But the process is complicated. Before bringing in a wrecking ball, a landlord must get permission from HCR to deny renewal leases to any regulated tenants in the building. If granted, tenants are owed sizable payments, which are calculated using a formula and were recently increased to keep pace with market rents.

“We generally tell a client it’s three to five years,” said Deborah Riegel of the law firm Rosenberg & Estis, who is not involved in the Eastern Parkway application. “Time is death in development. Things need to move and demos don’t move quickly.”

Renaissance filed its request in July 2023. The few remaining tenants immediately opposed it with an assist from Brooklyn Legal Services, saying demolition would violate a term in the building’s mortgage and could even be a bluff, given the apparently good condition of the empty apartments.

The tenants also accused their landlord of lowballing the concession payments HCR requires, in a ploy to make upfront buyouts look more attractive and lure them out faster.

At 73, Hicken has no interest in leaving the apartment she’s called home since the late 1970s, and which she shares with her adult son. Sitting in her living room in November, she recalled the years that she’d hear gunshots throughout the night: “boop, boop, boop.” Today, the neighborhood feels safe.

(Adi Talwar) Pamela Hicken in her living room at 285 Eastern Parkway in November 2023.

Hicken hopes to retire soon, but for now still works for Mount Sinai Hospital System. Her work computer is nestled among trophies from Star of Bethlehem, part of Enoch Grand Lodge in Bed-Stuy, where she’s associate matron. A stuffed tiger from her daughter surveys from the couch. “Look at my age,” she told City Limits. “Where am I going?”

Parker Winship, one of the attorneys assisting Hicken and her neighbors, believes Renaissance’s application shouldn’t be considered in isolation. The state legislature is currently debating modifications to the 2019 rent laws that could help landlords increase rents on an apartment-by-apartment basis.

But when it comes to building-wide deregulation, Winship sees Eastern Parkway as a bellwether, particularly for landlords in expensive neighborhoods like Crown Heights—it could inform whether they “decide to pursue demolition in the future.”