Scientists tame chaotic protein fueling 75% of cancers

MYC is the shapeless protein responsible for making the majority of human cancer cases worse. UC Riverside researchers have found a way to rein it in, offering hope for a new era of treatments.

Editors' notes

Scientists tame chaotic protein fueling 75% of cancers

by Jules Bernstein, University of California - Riverside

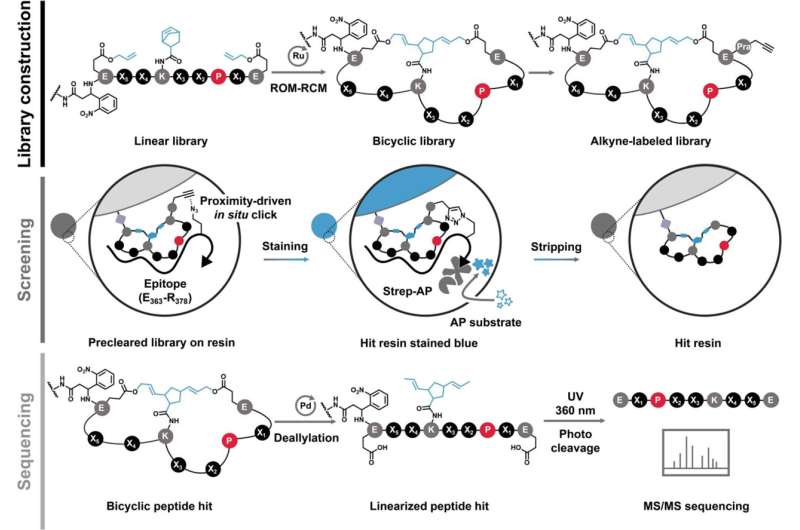

NTB bicyclic peptide library construction, MYC epitope screening, and chemical linearization of hit peptides followed by MS/MS sequencing. Credit: Journal of the American Chemical Society (2024). DOI: 10.1021/jacs.3c09615

MYC is the shapeless protein responsible for making the majority of human cancer cases worse. UC Riverside researchers have found a way to rein it in, offering hope for a new era of treatments.

In healthy cells, MYC helps guide the process of transcription, in which genetic information is converted from DNA into RNA and, eventually, into proteins. "Normally, MYC's activity is strictly controlled. In cancer cells, it becomes hyper active, and is not regulated properly," said UCR associate professor of chemistry Min Xue.

"MYC is less like food for cancer cells and more like a steroid that promotes cancer's rapid growth," Xue said. "That is why MYC is a culprit in 75% of all human cancer cases."

At the outset of this project the UCR research team believed that if they could dampen MYC's hyperactivity, they could open a window in which the cancer could be controlled.

However, finding a way to control MYC was challenging because unlike most other proteins, MYC has no structure. "It's basically a glob of randomness," Xue said. "Conventional drug discovery pipelines rely on well-defined structures, and this does not exist for MYC."

A new paper in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, on which Xue is the senior author, describes a peptide compound that binds to MYC and suppresses its activity.

In 2018, the researchers noticed that changing the rigidity and shape of a peptide improves its ability to interact with structureless protein targets such as MYC.

"Peptides can assume a variety of forms, shapes, and positions," Xue said. "Once you bend and connect them to form rings, they cannot adopt other possible forms, so they then have a low level of randomness. This helps with the binding."

In the paper, the team describes a new peptide that binds directly to MYC with what is called sub-micro-molar affinity, which is getting closer to the strength of an antibody. In other words, it is a very strong and specific interaction.

"We improved the binding performance of this peptide over previous versions by two orders of magnitude," Xue said. "This makes it closer to our drug development goals."

Currently, the researchers are using lipid nanoparticles to deliver the peptide into cells. These are small spheres made of fatty molecules, and they are not ideal for use as a drug. Going forward, the researchers are developing chemistry that improves the lead peptide's ability to get inside cells.

Once the peptide is in the cell, it will bind to MYC, changing MYC's physical properties and preventing it from performing transcription activities.

Xue's laboratory at UC Riverside develops molecular tools to better understand biology and uses that knowledge to perform drug discovery. He has long been interested in the chemistry of chaotic processes, which attracted him to the challenge of taming MYC.

"MYC represents chaos, basically, because it lacks structure. That, and its direct impact on so many types of cancer make it one of the holy grails of cancer drug development," Xue said. "We are very excited that it is now within our grasp."