You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

RUSSIA 🇷🇺 / РОССИЯ THREAD—ASSANGE CHRGD W/ SPYING—DJT IMPEACHED TWICE-US TREASURY SANCTS KILIMNIK AS RUSSIAN AGENT

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?

FBI Counterintelligence Agent Peter Strzok flat out says Trump is compromised via classified intel

Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani worked with an “active Russian agent” to discredit Joe Biden

Trump Lawyer Rudy Giuliani Worked With an “Active Russian Agent” to Discredit Joe Biden

The US Treasury Department says Andriy Derkach is a “Russia-linked election interference actor.”

Rudy Giuliani and President Donald Trump on Aug. 14 at an event at Trump's golf club in Bedminster, N.J.Susan Walsh/AP

A Ukrainian parliamentarian who has supplied Rudy Giuliani with information intended to smear Joe Biden has been “an active Russian agent for over a decade,” according to the US Treasury Department. On Thursday, Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control placed the official, Andriy Derkach, on a list of “Russia-linked election interference actors” and slapped him with financial sanctions.

“Derkach, a Member of the Ukrainian Parliament, has been an active Russian agent for over a decade, maintaining close connections with the Russian Intelligence Services,” the department said in an announcement. “Derkach has directly or indirectly engaged in, sponsored, concealed, or otherwise been complicit in foreign interference in an attempt to undermine the upcoming 2020 US presidential election.”

Treasury did not say where its information on Derkach comes from, but it is likely based on US intelligence findings. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence recently told Congress that Derkach is “spreading claims about corruption” as part of a Russian effort to undermine Biden’s campaign.

“Derkach and other Russian agents employ manipulation and deceit to attempt to influence elections in the United States and elsewhere around the world,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said in statement Thursday.

Along with Derkach, Treasury sanctioned three Russians it says are employed by Russia’s Internet Research Agency, a so-called troll-factory that took part in interference in the 2016 presidential election. The department says the IRA remains engaged in “malign influence operations around the world.”

Late last year—shortly before the House impeached Trump over his efforts to pressure Ukraine to help smear Biden—Giuliani traveled to Ukraine. During that trip, Giuliani met with Derkach and other Ukrainians who pushed baseless allegations that Biden had acted improperly in 2016 when, as vice president, he had joined an international push for the removal of Ukraine’s top prosecutor, Viktor Shokin, who was suspected of corruption.

Derkach held press conferences attacking former US Ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch, whose May 2019 ouster Giuliani helped to engineer. Beginning in May 2020, Derkach also held press conferences in Kiev during which he played a series of secretly recorded tapes of Biden speaking by phone with former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. The tapes did not revealwrongdoing by Biden, but Derkach asserted that they bolstered Trump’s and Giuliani’s allegations about Biden.

Ukrainians critical of Russia have theorized that the tapes were made by Russian intelligence. Derkach—who is the son of a former KGB officer and who attended a college in Moscow known for training spies—has denied this.

Giuliani told the Washington Post this summer that he remained in touch with Derkach after his December trip, calling the Ukrainian “very helpful.” Giuliani acknowledged that he and Derkach have spoken about Ukraine many times, according to the Post. Giuliani did not respond to requests for comment Thursday.

In a statement Thursday to BuzzFeed News, Derkach claimed Treasury sanctioned him as “revenge” by Biden’s “deep state associates” and to preempt a new press conference he says he plans to hold early next week to reveal supposed corruption by Democrats.

The New York Times and Politico have reported that Democrats, in a classified portion of a July letter to FBI Director Christopher Wray, alleged that Derkach is part of an effort to launder Russian disinformation through a US Senate investigation overseen by Ron Johnson (R-Wis.) into Biden and Ukraine. Derkach has also reportedly sent information related to Biden to other congressional Republicans including Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa). Johnson and Grassley have said they did not receive material from Derkach.

“Foreign election meddling in all of its forms from any corner of the globe cannot be tolerated,” Johnson and Grassley said in a joint statement Thursday. “We commend the Trump Administration for holding accountable perpetrators of foreign interference, and hope our Democratic colleagues in Congress will finally stop relying on disinformation from the likes of Andriy Derkach to smear their political rivals.”

theweek.com

How the Trump-Russia story was buried

Illustrated | Getty Images, iStock

September 16, 2020

The biggest political story of 2016-19 was largely wrapped up this August, and it only made a blip in the news. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) published the final volume of its enormous investigation into how the Russian government influenced the 2016 election, this time focusing on how the Trump campaign was involved (what has become known as "Russiagate"). Remarkably, the committee is led by Republicans due to their Senate majority — a reasonable sign it was a credible investigation. Since then, there has been a steady drip of reporting about Russia's apparent effort to influence this year's election, like President Trump's own Treasury Department sanctioning a Ukrainian friend of Rudy Giuliani for allegedly doing just that.

This volume of the report is nearly 1,000 pages long, but at bottom the story is pretty simple. Essentially, the suspicion your average ordinary liberal had from the start was correct. The Trump campaign did conspire in secret (as well as openly) with Russian intelligence. The Trump campaign knew Russia was behind the email hacking of Hillary Clinton's campaign manager John Podesta and the Democratic National Committee, and very likely coordinated with WikiLeaks about the emails being dribbled out in a fashion calculated to inflict maximum damage to Clinton.

It's peculiar that the resolution of this story — which dominated front pages for months on end — has not gotten more attention. Part of the explanation, no doubt, is the coronavirus pandemic, ongoing economic crisis, and looming election. But another is how the Russiagate story hits the blind spots of practically every American political faction. Many liberals and conservatives succumbed to paranoia about the story, while many leftists took that paranoia as proof the story was nothing. So it was buried.

But first, the details of this latest report. SSCI found that Trump's former campaign chairman Paul Manafort (who was convicted of multiple counts of bank and tax fraud as part of the Mueller investigation), was in regular contact with Konstantin Kilimnik, a Russian intelligence agent. Manafort gave him regular updates of confidential Trump campaign information, including polling and strategy details. Kilimnik was likely part of the Russian hacking effort, and he was also in close connection with the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, a Putin ally who has been involved in election influence schemes in other countries, as well as the effort to shift blame away from Russia for the 2016 hack.

Meanwhile, WikiLeaks (which distributed the hacked emails) "actively sought, and played, a key role in the Russian influence campaign and very likely knew it was assisting a Russian intelligence influence effort," the report states. The Trump campaign was aware multiple sources had attributed the hack to Russia, and "sought to obtain advance information about WikiLeaks's planned releases through Roger Stone," who did indeed reach out to WikiLeaks privately. Though SSCI could not confirm Stone actually delivered any non-public information, "Trump and the campaign believed that Stone had inside information and expressed satisfaction that Stone's information suggested more releases would be forthcoming."

In sum, the Trump campaign worked with the right-wing authoritarian government of Russia, which illegally stole private communications and leveraged them to corrupt the democratic process by tricking the American people about which candidate was more corrupt. The "emails" story got more front-page New York Times coverage in six days than all policy topics combined got in 69 days — drowning out coverage of the dozen-plus far worse Trump corruption stories.

These conclusions add details and certainty to the report published by Special Counsel Robert Mueller back in 2019, which found multiple instances of Trump at least attempting (and arguably succeeding) to obstruct the investigation, and related other meetings Trump campaign operatives had with Russian intelligence, but did not complete the Kilimnik story, nor confirm the Stone back channel.

Recall that before the Mueller report was made public, Attorney General (and shameless Trump stooge) William Barr lied through his teeth about what it said. And wouldn't you know it, new reporting also calls into question another aspect of the Mueller report that supposedly exonerated Trump — that his investigators found no direct connection between the president and Russia. Michael Schmidt of The New York Times reports that in 2017, then-Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein instructed Mueller not to directly investigate Trump's ties with Russia. Rosenstein also did not tell the FBI brass, which had opened its own investigation, that he did this. In other words, Mueller found no direct connection between Trump and Russia because he was instructed not to look into it.

There are still some missing pieces to the story (and the SSCI report has many redactions), but the basic outline of the story is there for those with eyes to see.

In retrospect, we can see how the Russiagate story unfortunately played into the biases of various political factions. The neocon #NeverTrump center-right naturally found it most compelling, with its Cold War bad guy. They folded the Russia story into their broader politics, arguing that this proved Trump was weak on national security and what America needs is to stand up to Vladimir Putin. "The Trump presidency’s connections to Russia are a national-security issue first, a criminal-justice issue only second," as David Frum wrote at The Atlantic in 2018. But this stance plainly does not play well in a country that is ever-more exhausted with war and wary of international conflicts. Given the lack of appetite for a confrontation with Russia, the neocons have resigned themselves to political defeat, at least for the moment.

The center-left also found the story appealing at first, and gave rapt coverage to every twist and turn of the Mueller investigation. Some of them, like anonymous business consultant turned #Resistance Twitter celebrity Eric Garland, went completely off the deep end over it, while others like MSNBC's Rachel Maddow allowed it to displace coverage of practically every other story for a time. Others have written hyperbolic stories about Russian spying, like a recent Daily Beast article that trumps up a Russian "infiltration" operation of left-wing magazines that amounted to a garbled unsolicited pitch. But even among relatively sensible commentators and politicians there was a hopeful expectation that Mueller would be the one to nail Trump, thereby excusing the Democratic leadership from having to do politics. If all the loyal Republican patriots in the national security bureaucracy could bring Trump down for treason, then the republic could be saved without Democrats having to beat the GOP in the political arena.

Last edited:

PART 2:

Alas, it was not to be. Multiple people in the Trump orbit did indeed get charged and convicted of crimes, but Trump has already commuted the sentence of WikiLeaks back channel Roger Stone, is signaling that other pardons will probably come, and he himself has skated on any accountability. Once it became clear that Mueller was not allowed to indict Trump despite his findings of very likely obstruction of justice, and that absolutely nothing could convince Senate Republicans to vote to remove him from office after he was impeached, the center-left largely gave up on the story too.

All that said, elements of the left bungled the story worse than either of the previous two factions. The fact that neocons and the center-left were agreeing about something set off instinctive warning bells — and rightly so, because that often signals something terrible, like on October 10, 2002. It also seemed, again probably rightly, that the Democrats and the Clinton campaign were attempting to excuse their abysmal 2016 performance by blaming the loss on Russia. It wasn't our grossly unpopular candidate or her data whiz advisers deciding not to campaign in swing states that did it — it was dastardly foreigners!

All those were important caveats to keep in mind. But they were no excuse to simply not examine the details of such a big story, much less baldly misrepresent them. Yet that is precisely what many ostensibly lefty voices have done. People like The Intercept's Glenn Greenwald and independent writers Michael Tracey and Matt Taibbi seized on every failed liberal prediction to cast doubt on the overall story. When leaks emerged reporting that Mueller’s investigation was completed with no new prosecutions, Taibbi concluded: "It’s official: Russiagate is this generation’s WMD." Then, when Barr released his lying summary of the Mueller report, they swallowed it hook, line, and sinker, gleefully declared victory, and concluded the whole thing was garbage. The summary proved the whole thing was "unhinged conspiratorial trash," wrote Greenwald. A "roughly 33-month national ordeal" is over, wrote Taibbi. Tracey — perhaps the most tendentious #Slatepitch contrarian writing today — had clockwork outbreaks of shrieking hysterics online for weeks over how "disgusting media scumbags" had perpetuated "a deranged 3-year hoax."

Naturally, since the SSCI report came out weeks ago, none of them have updated their views, or indeed written a single word about it that I can find.

Incidentally, this is an important lesson in how propaganda works. Taking a hard look at the evidence in a complicated story and coming to a measured conclusion with all the proper caveats is tedious and boring. Seizing on a convenient half- or quarter- or twentieth-truth, or straight-up falsehood, and loudly repeating it 10 million times sticks in people's minds. It works even better if you take that wrong belief, declare it to be proved beyond any question 10 million more times, and start furiously demanding recriminations from people who disagree with you.

Thus, through a sustained campaign of ideological battering, Russiagate basically became a non-story on the left. People either came to believe that it was all nonsense, or they got so fed up with arguing with aggressive bad-faith B.S. that they figured it wasn't worth the bother. It was particularly jarring coming from Greenwald, who wrote an entire book back in 2011 about elite impunity with an extensive discussion about the Iran-Contra coverup — in which Barr was a central player. But when it was convenient to believe so, suddenly Barr was a reliable source.

Moreover, this stance was pretty much exactly what Trump himself and his corrupt cronies said about the story.

So, with moderate factions either way out over their skis or losing interest in the story, and the far right and some on the left agreeing it was not even real, the mainstream press largely lost interest as well. The SSCI report did get coverage, but it was largely perfunctory — wondering if voters would care about the story at all.

The fact that a literally murderous right-wing autocrat meddled in the American political system and is very probably doing so again is a genuinely difficult analytical challenge. On the one hand, the neocons are wrong in their conclusions. Aggressive confrontation with Putin is half the reason the U.S. got into this mess in the first place, and what the U.S. needs above all right now is de-escalation and diplomacy, especially given how tensions have ratcheted up between American and Russian forces on the ground in various places (apparently over disputes regarding control of Syria).

But on the other hand, the left contrarians are also wrong. This is not a fake, overhyped story — on the contrary, it's one of the biggest stories of political corruption and white-collar criminality in decades, and should by rights be towards the top of the Trump administration's very long list of crimes.

Finally, contrary to the hopes of the center-left, Trump will not be held to account by a Senate committee or law enforcement agencies on their own. The only way for it to happen at this point is for Joe Biden to win the presidency and then commit to exercising his power to make it happen. Greenwald was right about elite impunity in 2011 (as was Taibbi when he wrote a similar book in 2014). It was a terrible mistake for President Obama to sweep all the Bush administration's torture crimes under the rug, and doing so again with Trump's record might well doom America's democratic institutions. When people in power get away with crimes, sooner or later outright criminals will get into high office and start stealing elections.

Biden is probably going to resist seriously investigating Trump. It would help encourage him if all Americans in favor of the rule of law could agree that his crimes are, in fact, crimes, even if it means momentarily agreeing with some MSNBC liberals.

CORRECTION: This article originally misstated the timing of Matt Taibbi's comparison of Russiagate to WMDs. The article also originally mischaracterized Deripaska's connection to the 2016 hack. Both mistakes have been corrected. The Week regrets the errors.

@88m3 @ADevilYouKhow @wire28 @dtownreppin214

@dza @wire28 @BigMoneyGrip @Dameon Farrow @re'up @Blackfyre @NY's #1 Draft Pick @Skyfall @2Quik4UHoes

Alas, it was not to be. Multiple people in the Trump orbit did indeed get charged and convicted of crimes, but Trump has already commuted the sentence of WikiLeaks back channel Roger Stone, is signaling that other pardons will probably come, and he himself has skated on any accountability. Once it became clear that Mueller was not allowed to indict Trump despite his findings of very likely obstruction of justice, and that absolutely nothing could convince Senate Republicans to vote to remove him from office after he was impeached, the center-left largely gave up on the story too.

All that said, elements of the left bungled the story worse than either of the previous two factions. The fact that neocons and the center-left were agreeing about something set off instinctive warning bells — and rightly so, because that often signals something terrible, like on October 10, 2002. It also seemed, again probably rightly, that the Democrats and the Clinton campaign were attempting to excuse their abysmal 2016 performance by blaming the loss on Russia. It wasn't our grossly unpopular candidate or her data whiz advisers deciding not to campaign in swing states that did it — it was dastardly foreigners!

All those were important caveats to keep in mind. But they were no excuse to simply not examine the details of such a big story, much less baldly misrepresent them. Yet that is precisely what many ostensibly lefty voices have done. People like The Intercept's Glenn Greenwald and independent writers Michael Tracey and Matt Taibbi seized on every failed liberal prediction to cast doubt on the overall story. When leaks emerged reporting that Mueller’s investigation was completed with no new prosecutions, Taibbi concluded: "It’s official: Russiagate is this generation’s WMD." Then, when Barr released his lying summary of the Mueller report, they swallowed it hook, line, and sinker, gleefully declared victory, and concluded the whole thing was garbage. The summary proved the whole thing was "unhinged conspiratorial trash," wrote Greenwald. A "roughly 33-month national ordeal" is over, wrote Taibbi. Tracey — perhaps the most tendentious #Slatepitch contrarian writing today — had clockwork outbreaks of shrieking hysterics online for weeks over how "disgusting media scumbags" had perpetuated "a deranged 3-year hoax."

Naturally, since the SSCI report came out weeks ago, none of them have updated their views, or indeed written a single word about it that I can find.

Incidentally, this is an important lesson in how propaganda works. Taking a hard look at the evidence in a complicated story and coming to a measured conclusion with all the proper caveats is tedious and boring. Seizing on a convenient half- or quarter- or twentieth-truth, or straight-up falsehood, and loudly repeating it 10 million times sticks in people's minds. It works even better if you take that wrong belief, declare it to be proved beyond any question 10 million more times, and start furiously demanding recriminations from people who disagree with you.

Thus, through a sustained campaign of ideological battering, Russiagate basically became a non-story on the left. People either came to believe that it was all nonsense, or they got so fed up with arguing with aggressive bad-faith B.S. that they figured it wasn't worth the bother. It was particularly jarring coming from Greenwald, who wrote an entire book back in 2011 about elite impunity with an extensive discussion about the Iran-Contra coverup — in which Barr was a central player. But when it was convenient to believe so, suddenly Barr was a reliable source.

Moreover, this stance was pretty much exactly what Trump himself and his corrupt cronies said about the story.

So, with moderate factions either way out over their skis or losing interest in the story, and the far right and some on the left agreeing it was not even real, the mainstream press largely lost interest as well. The SSCI report did get coverage, but it was largely perfunctory — wondering if voters would care about the story at all.

The fact that a literally murderous right-wing autocrat meddled in the American political system and is very probably doing so again is a genuinely difficult analytical challenge. On the one hand, the neocons are wrong in their conclusions. Aggressive confrontation with Putin is half the reason the U.S. got into this mess in the first place, and what the U.S. needs above all right now is de-escalation and diplomacy, especially given how tensions have ratcheted up between American and Russian forces on the ground in various places (apparently over disputes regarding control of Syria).

But on the other hand, the left contrarians are also wrong. This is not a fake, overhyped story — on the contrary, it's one of the biggest stories of political corruption and white-collar criminality in decades, and should by rights be towards the top of the Trump administration's very long list of crimes.

Finally, contrary to the hopes of the center-left, Trump will not be held to account by a Senate committee or law enforcement agencies on their own. The only way for it to happen at this point is for Joe Biden to win the presidency and then commit to exercising his power to make it happen. Greenwald was right about elite impunity in 2011 (as was Taibbi when he wrote a similar book in 2014). It was a terrible mistake for President Obama to sweep all the Bush administration's torture crimes under the rug, and doing so again with Trump's record might well doom America's democratic institutions. When people in power get away with crimes, sooner or later outright criminals will get into high office and start stealing elections.

Biden is probably going to resist seriously investigating Trump. It would help encourage him if all Americans in favor of the rule of law could agree that his crimes are, in fact, crimes, even if it means momentarily agreeing with some MSNBC liberals.

CORRECTION: This article originally misstated the timing of Matt Taibbi's comparison of Russiagate to WMDs. The article also originally mischaracterized Deripaska's connection to the 2016 hack. Both mistakes have been corrected. The Week regrets the errors.

@88m3 @ADevilYouKhow @wire28 @dtownreppin214

@dza @wire28 @BigMoneyGrip @Dameon Farrow @re'up @Blackfyre @NY's #1 Draft Pick @Skyfall @2Quik4UHoes

Last edited:

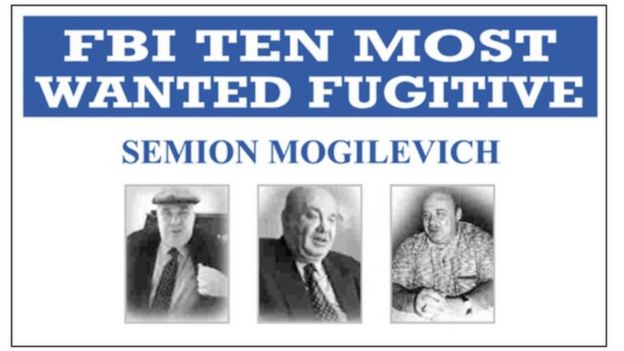

MOGILEVICH

FIRTASH

DERIPASKA

MANAFORT

Global banks defy U.S. crackdowns by serving oligarchs, criminals and terrorists - ICIJ

‘Boss of bosses’

Often, the secret files show, banks handling cross-border transactions have little idea who they’re dealing with — even when they’re shifting hundreds of millions of dollars.

Take the case of a mysterious shell company called ABSI Enterprises. ABSI sent and received more than $1 billion in transactions through JPMorgan between January 2010 and July 2015, the FinCEN Files show.

This amount included transactions through a direct bank account with JPMorgan, which ABSI closed in 2013, and through so-called correspondent banking arrangements, in which a bank with significant U.S. operations, such as JPMorgan, allows foreign banks to process U.S. dollar transactions through its own accounts.

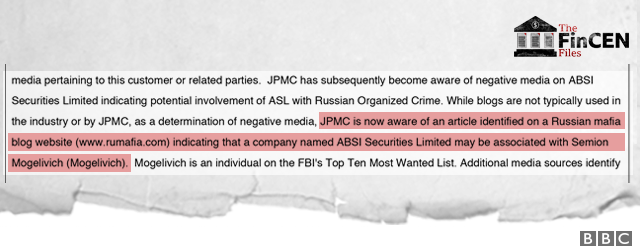

Compliance watchdogs based at the bank’s Columbus, Ohio, operations hub decided to try to figure out ABSI’s actual owner in 2015 after a Russian news site reported that a similarly-named shell company — which JPMorgan’s records indicated was the parent of ABSI — was linked to an underworld figure named Semion Mogilevich.

Mogilevich has been described as the “Boss of Bosses” of Russia mafia groups. When the FBI put him on its Top Ten Most Wanted list in 2009, it said his criminal network was involved in weapons and drug trafficking, extortion and contract murders. The chain-smoking, beefy Ukrainian’s signature method of neutralizing an enemy, The Guardian once reported, is the car bomb.

The records show the compliance officers searched in vain through their files on the shell company, unable to determine who was behind the firm or what its true purpose was.

While those details still remain unclear, JPMorgan had plenty of reasons to examine ABSI years earlier: it operated as a shell company in Cyprus, considered a major money laundering center at the time, and it was directing hundreds of millions of dollars through JPMorgan.

Mogilevich is featured in “World’s Most Wanted,” a Netflix documentary series released in August.

Through a spokesperson, Mogilevich said he had no knowledge of ABSI.

He has previously said: “I am not a leader or an active participant of any criminal group.”

...

Bank of New York Mellon was among the first big banks to pay a large penalty to U.S. authorities for anti-money-laundering failures. In 2005, two years before its merger with Mellon Financial, Bank of New York paid $38 million dollars and signed a non-prosecution agreement after a federal probe concluded that it had allowed $7 billion in illicit Russian money to flow through its accounts.

Media reports said investigators believed that Mogilevich, the alleged Russian mafia “Boss of Bosses,” was behind some of the transactions.

Even as it’s avoided big money laundering enforcement actions in recent years, Bank of New York Mellon has continued doing business with suspect figures, the FinCEN Files show.

The leaked records show, for example, that Bank of New York Mellon moved more than $1.3 billion in transactions between 1997 and 2016 tied to Oleg Deripaska, a Russia billionaire and a longtime ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Since 2008, Deripaska has been the subject of allegations in media reports tying him to organized crime. When U.S. authorities announced sanctions against him in 2018, they said he had been previously been accused of threatening the lives of corporate rivals, bribing a Russian government official and ordering the murder of a businessman.

Deripaska denies laundering funds or committing financial crimes. In 2019 the Trump administration lifted sanctions on three companies linked to him. U.S. sanctions on Deripaska himself remain and he’s suing in an effort to upend them.

“BNY Mellon takes its role in protecting the integrity of the global financial system seriously, including filing Suspicious Activity Reports,” the bank said in a statement. “As a trusted member of the international banking community, we fully comply with all applicable laws and regulations, and assist authorities in the important work they do.”

...

Red flags

One striking pattern revealed by ICIJ’s analysis of the leaked records is the willingness of multiple banks to process transactions for the same risky clients.

Deripaska, the Russian oligarch, didn’t just have Bank of New York Mellon helping him out. The secret records reveal Deutsche Bank shuffled more than $11 billion in transactions between 2003 and 2017 for companies he controlled.

The records also indicate that Deutsche Bank and Standard Chartered helped Odebrecht SA — a Latin American construction firm behind what U.S. prosecutors called the largest foreign bribery case in history — move $677 million from 2010 from 2016. Deutsche Bank played a role in transactions involving more than $560 million of that amount, the records show.

Then there’s Dmytro Firtash, a Ukrainian oligarch who is wanted on criminal charges in the U.S.

In 2014, American prosecutors unsealed an indictment accusing him of bribing officials in India in an effort to secure a mining deal. Since late 2019, U.S. news outlets have reported on claims that Firtash played a role in President Trump’s effort to dig up dirt in Ukraine on his 2020 reelection opponent, Joe Biden.

Firtash, who says he began his climb in business trading Ukrainian powdered milk for Uzbek cotton after the fall of the Soviet Union, lives in exile in a mansion in Vienna, protected so far from efforts to extradite him. His Art Nouveau villa has a home cinema and an infinity pool — a 2017 profile by Bloomberg Businessweek dubbed him “the Oligarch in the Gilded Cage.”

When it comes to banking, he and companies tied to him found open doors among many of the industry’s big institutions.

All five big banks in ICIJ’s analysis — JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered, HSBC and Bank of New York Mellon — handled transactions for companies controlled by Firtash, the FinCEN Files show. And the records indicate that all five approved transactions tied to Firtash in the time periods after U.S. authorities had forced the banks to pay fines and pledge to work harder to vet suspect clients.

The files show that among these banks, JPMorgan moved the most money for companies controlled by Firtash by far — shuffling hundreds of transactions totaling nearly $2 billion between 2003 and 2014.

JPMorgan and the other banks should have been aware of Firtash’s questionable history as far back as 2010, when a leaked U.S. diplomatic cable linked Firtash to Mogilevich.

Then in 2011, a lawsuit filed in Manhattan by former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko provided the banks even more of a heads up, even naming specific accounts at four of the banks that the suit alleged were being used by Firtash for money laundering.

The suit accused Firtash, Mogilevich and future Trump campaign manager Manafort of laundering illicit funds from Ukraine through banks and investment deals in the U.S.

The suit claimed accounts at the New York offices of JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered and Bank of New York Mellon were being used in money laundering operations shifting money stolen in Ukraine to the U.S. and then — after it had been cleaned — round-tripping it back to Ukraine.

Despite the allegations, these five banks continued to handle transactions involving companies controlled by Firtash, the FinCEN Files show.

The lawsuit was dismissed in 2013, in part because Tymoshenko and her lawyers weren’t able to provide enough specifics of the transactions involved in the alleged scheme.

Firtash has denied wrongdoing, telling Bloomberg Businessweek that he’s the victim of “a special machine of propaganda organized against me.” He told the magazine that Tymoshenko was “wrong in everything. She lies all the time. In order to money launder, you need to have dirty money to start with. I always had clean money.”

In a statement, an attorney for Firtash told ICIJ that Firtash “has never had any partnership or other commercial association with Semion Mogilevich.” The attorney said Firtash would not answer questions from ICIJ because its queries are “reliant on the unlawful and criminal disclosure” of suspicious activity reports.

Often, the secret files show, banks handling cross-border transactions have little idea who they’re dealing with — even when they’re shifting hundreds of millions of dollars.

Take the case of a mysterious shell company called ABSI Enterprises. ABSI sent and received more than $1 billion in transactions through JPMorgan between January 2010 and July 2015, the FinCEN Files show.

This amount included transactions through a direct bank account with JPMorgan, which ABSI closed in 2013, and through so-called correspondent banking arrangements, in which a bank with significant U.S. operations, such as JPMorgan, allows foreign banks to process U.S. dollar transactions through its own accounts.

Compliance watchdogs based at the bank’s Columbus, Ohio, operations hub decided to try to figure out ABSI’s actual owner in 2015 after a Russian news site reported that a similarly-named shell company — which JPMorgan’s records indicated was the parent of ABSI — was linked to an underworld figure named Semion Mogilevich.

Mogilevich has been described as the “Boss of Bosses” of Russia mafia groups. When the FBI put him on its Top Ten Most Wanted list in 2009, it said his criminal network was involved in weapons and drug trafficking, extortion and contract murders. The chain-smoking, beefy Ukrainian’s signature method of neutralizing an enemy, The Guardian once reported, is the car bomb.

The records show the compliance officers searched in vain through their files on the shell company, unable to determine who was behind the firm or what its true purpose was.

While those details still remain unclear, JPMorgan had plenty of reasons to examine ABSI years earlier: it operated as a shell company in Cyprus, considered a major money laundering center at the time, and it was directing hundreds of millions of dollars through JPMorgan.

Mogilevich is featured in “World’s Most Wanted,” a Netflix documentary series released in August.

Through a spokesperson, Mogilevich said he had no knowledge of ABSI.

He has previously said: “I am not a leader or an active participant of any criminal group.”

...

Bank of New York Mellon was among the first big banks to pay a large penalty to U.S. authorities for anti-money-laundering failures. In 2005, two years before its merger with Mellon Financial, Bank of New York paid $38 million dollars and signed a non-prosecution agreement after a federal probe concluded that it had allowed $7 billion in illicit Russian money to flow through its accounts.

Media reports said investigators believed that Mogilevich, the alleged Russian mafia “Boss of Bosses,” was behind some of the transactions.

Even as it’s avoided big money laundering enforcement actions in recent years, Bank of New York Mellon has continued doing business with suspect figures, the FinCEN Files show.

The leaked records show, for example, that Bank of New York Mellon moved more than $1.3 billion in transactions between 1997 and 2016 tied to Oleg Deripaska, a Russia billionaire and a longtime ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Since 2008, Deripaska has been the subject of allegations in media reports tying him to organized crime. When U.S. authorities announced sanctions against him in 2018, they said he had been previously been accused of threatening the lives of corporate rivals, bribing a Russian government official and ordering the murder of a businessman.

Deripaska denies laundering funds or committing financial crimes. In 2019 the Trump administration lifted sanctions on three companies linked to him. U.S. sanctions on Deripaska himself remain and he’s suing in an effort to upend them.

“BNY Mellon takes its role in protecting the integrity of the global financial system seriously, including filing Suspicious Activity Reports,” the bank said in a statement. “As a trusted member of the international banking community, we fully comply with all applicable laws and regulations, and assist authorities in the important work they do.”

...

Red flags

One striking pattern revealed by ICIJ’s analysis of the leaked records is the willingness of multiple banks to process transactions for the same risky clients.

Deripaska, the Russian oligarch, didn’t just have Bank of New York Mellon helping him out. The secret records reveal Deutsche Bank shuffled more than $11 billion in transactions between 2003 and 2017 for companies he controlled.

The records also indicate that Deutsche Bank and Standard Chartered helped Odebrecht SA — a Latin American construction firm behind what U.S. prosecutors called the largest foreign bribery case in history — move $677 million from 2010 from 2016. Deutsche Bank played a role in transactions involving more than $560 million of that amount, the records show.

Then there’s Dmytro Firtash, a Ukrainian oligarch who is wanted on criminal charges in the U.S.

In 2014, American prosecutors unsealed an indictment accusing him of bribing officials in India in an effort to secure a mining deal. Since late 2019, U.S. news outlets have reported on claims that Firtash played a role in President Trump’s effort to dig up dirt in Ukraine on his 2020 reelection opponent, Joe Biden.

Firtash, who says he began his climb in business trading Ukrainian powdered milk for Uzbek cotton after the fall of the Soviet Union, lives in exile in a mansion in Vienna, protected so far from efforts to extradite him. His Art Nouveau villa has a home cinema and an infinity pool — a 2017 profile by Bloomberg Businessweek dubbed him “the Oligarch in the Gilded Cage.”

When it comes to banking, he and companies tied to him found open doors among many of the industry’s big institutions.

All five big banks in ICIJ’s analysis — JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered, HSBC and Bank of New York Mellon — handled transactions for companies controlled by Firtash, the FinCEN Files show. And the records indicate that all five approved transactions tied to Firtash in the time periods after U.S. authorities had forced the banks to pay fines and pledge to work harder to vet suspect clients.

The files show that among these banks, JPMorgan moved the most money for companies controlled by Firtash by far — shuffling hundreds of transactions totaling nearly $2 billion between 2003 and 2014.

JPMorgan and the other banks should have been aware of Firtash’s questionable history as far back as 2010, when a leaked U.S. diplomatic cable linked Firtash to Mogilevich.

Then in 2011, a lawsuit filed in Manhattan by former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko provided the banks even more of a heads up, even naming specific accounts at four of the banks that the suit alleged were being used by Firtash for money laundering.

The suit accused Firtash, Mogilevich and future Trump campaign manager Manafort of laundering illicit funds from Ukraine through banks and investment deals in the U.S.

The suit claimed accounts at the New York offices of JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered and Bank of New York Mellon were being used in money laundering operations shifting money stolen in Ukraine to the U.S. and then — after it had been cleaned — round-tripping it back to Ukraine.

Despite the allegations, these five banks continued to handle transactions involving companies controlled by Firtash, the FinCEN Files show.

The lawsuit was dismissed in 2013, in part because Tymoshenko and her lawyers weren’t able to provide enough specifics of the transactions involved in the alleged scheme.

Firtash has denied wrongdoing, telling Bloomberg Businessweek that he’s the victim of “a special machine of propaganda organized against me.” He told the magazine that Tymoshenko was “wrong in everything. She lies all the time. In order to money launder, you need to have dirty money to start with. I always had clean money.”

In a statement, an attorney for Firtash told ICIJ that Firtash “has never had any partnership or other commercial association with Semion Mogilevich.” The attorney said Firtash would not answer questions from ICIJ because its queries are “reliant on the unlawful and criminal disclosure” of suspicious activity reports.

HSBC moved scam millions, big banking leak shows

What else did the leak find?

The FinCEN Files also show how multinational bank JP Morgan may have helped a man known as the Russian mafia's boss of bosses to move more than a $1bn through the financial system.

Semion Mogilevich has been accused of crimes including gun running, drug trafficking and murder.

He should not be allowed to use the financial system, but a SAR filed by JP Morgan in 2015 after the account was closed, reveals how the bank's London office may have moved some of the cash.

It details how JP Morgan, provided banking services to a secretive offshore company called ABSI Enterprises between 2002 and 2013, even though the firm's ownership was not clear from the bank's records.

Over one five-year period, JP Morgan sent and received wire transfers totalling $1.02bn, the bank said.

The SAR noted ABSI's parent company "might be associated with Semion Mogilevich - an individual who was on the FBI's top 10 most wanted list".

In a statement, JP Morgan said: "We follow all laws and regulations in support of the government's work to combat financial crimes. We devote thousands of people and hundreds of millions of dollars to this important work."

@88m3 @ADevilYouKhow @wire28 @dtownreppin214

@dza @wire28 @BigMoneyGrip @Dameon Farrow @re'up @Blackfyre @NY's #1 Draft Pick @Skyfall @2Quik4UHoes

Top Mueller prosecutor: "We could have done more"

Shane Savitsky

Former special counsel Robert Mueller. Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

Andrew Weissmann, one of former special counsel Robert Mueller's top prosecutors, says in his new book, "Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation," that the probe "could have done more" to take on President Trump, per The Atlantic.

Why it matters ... Weissmann argues that the investigation's report didn't go far enough in making a determination regarding Trump's potential obstruction of justice: "When there is insufficient proof of a crime, in volume one, we say it. But when there is sufficient proof, with obstruction, we don’t say it. Who is going to be fooled by that? It’s so obvious."

- "Had we given it our all—had we used all available tools to uncover the truth, undeterred by the onslaught of the president’s unique powers to undermine our efforts?" Weissmann asks in the book's introduction.

- "Part of the reason the president and his enablers were able to spin the report was that we had left the playing field open for them to do so."

- The document's final words: "Accordingly, while this report does not conclude that the President committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him."

- That allowed Attorney General Bill Barr to say that the Department of Justice had concluded that the evidence was "not sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense," noting that the government would have to prove such a case "beyond a reasonable doubt."

Go deeper: 7 takeaways from the Mueller report

@88m3 @ADevilYouKhow @wire28 @dtownreppin214

@dza @wire28 @BigMoneyGrip @Dameon Farrow @re'up @Blackfyre @NY's #1 Draft Pick @Skyfall @2Quik4UHoes

Mueller’s Team Should Have Done More to Investigate Trump-Russia Links, Top Aide Says

nytimes.com

Mueller’s Team Should Have Done More to Investigate Trump-Russia Links, Top Aide Says

By Charlie Savage

12-15 minutes

A new book by one of the special counsel’s top deputies, Andrew Weissmann, is the first inside account of the investigation.

Credit...Hilary Swift for The New York Times

“Had we used all available tools to uncover the truth, undeterred by the onslaught of the president’s unique powers to undermine our efforts?” wrote the former prosecutor, Andrew Weissmann, in a new book, adding, “I know the hard answer to that simple question: We could have done more.”

The team took elaborate steps to protect its files of evidence from the risk that the Justice Department might destroy them if Mr. Trump fired them and worked to keep reporters and the public from learning what they were up to, Mr. Weissmann wrote in “Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation,” which Random House will publish next week.

While he speaks reverently of Mr. Mueller, he also says his boss’s diffidence made him ill-suited for aspects of shepherding the politically charged investigation. He saw Mr. Mueller and his deputy, Aaron M. Zebley, as overly cautious.

Mr. Weissmann also defended against accusations by the president and his allies that he and other investigators were politically biased “angry Democrats”; Mr. Weissmann said his personal views had no bearing on the crimes that Russian operatives and Trump aides committed.

And he elevates particular details — for example, emphasizing that the same business account that sent hush payments to an adult film star who alleged an extramarital affair with Mr. Trump had also received “payments linked to a Russian oligarch.” The president has denied the affair; his former lawyer Michael D. Cohen controlled the account. Mr. Mueller transferred the Cohen matter to prosecutors in New York.

Previously a mafia and Enron prosecutor and then a lawyer at the F.B.I. for Mr. Mueller, who was the bureau’s director for 12 years, Mr. Weissmann ran one of three major units for the special counsel’s office. His “Team M” prosecuted Mr. Trump’s former campaign chairman Paul Manafort for numerous financial crimes. The goal was to flip him and learn whatever he knew about any Trump campaign links to Russia.

Mr. Manafort had worked for pro-Russian interests in Ukraine, and the investigation uncovered ties by his business partner, Konstantin V. Kilimnik, to Russian intelligence. The book builds toward investigators’ discovery that Mr. Manafort had shared internal campaign polling data with Mr. Kilimnik, who flew to the United States to meet with Mr. Manafort during the campaign, asking whether Mr. Trump would permit a peace plan for Russia to essentially take over all of eastern Ukraine.

But while admitting this much, Mr. Manafort — seeing the dangle of a potential pardon from Mr. Trump — refused to cooperate further. Investigators did not obtain any final puzzle pieces and lacked the evidence to charge anyone in the campaign with a criminal conspiracy involving Russia’s covert electoral assistance.

“It would seem to require significant audacity — or else, leverage — for another nation to even put such a request before a presidential candidate,” Mr. Weissmann wrote of Mr. Kilimnik’s request. “This made what we didn’t know, and still don’t know to this day, monumentally disconcerting: Namely, why would Trump ever agree to this? Why would Trump ever agree to this Russian proposal if the candidate were not getting something from Russia in return?”

Mr. Weissmann explained the significance of Mr. Manafort’s interactions with Mr. Kilimnik — also a major focus of a recent bipartisan Senate Intelligence Committee report, which explicitly labeled Mr. Kilimnik a Russian intelligence agent — more clearly than the Mueller report did.

Mr. Mueller had strictly forbidden leaks, and the special counsel team took extraordinary care to protect the high-profile, high-stakes investigation, Mr. Weissmann wrote. They kept window blind slats tilted at an angle to keep out prying eyes, shutting out natural light. They concocted an “almost comically elaborate and surreal” plan to sneak in “through the many hidden arteries of the courthouse” to obtain a grand jury indictment without tipping off reporters.

And worried about the possibility that Mr. Trump would fire them and the Justice Department would then seal off or destroy their evidence, the Mueller team members packed their numerous applications to judges for search warrants with extensive, up-to-date details about their investigation — ensuring they backed up their work beyond the reach of the executive branch.

Ty Cobb, a lawyer for Mr. Trump, also privately promised to be a “canary in the coal mine” and provide a heads up if Mr. Trump was going to fire the special counsel team, according to Mr. Weissmann. In an email, Mr. Cobb wrote that he “never made the commitment” described by Mr. Weissmann.

The investigation played out against the backdrop of regular vilification of the Mueller team by Mr. Trump and his allies like Fox News’s Sean Hannity — who turned out to be in regular contact with Mr. Manafort cooking up a “smear campaign” over text messages. Mr. Weissmann, a major target, wrote that such “ad hominem” insinuations of bias appealed to emotion rather than reason.

“I am a registered Democrat,” he wrote. “Does this make Paul Manafort or any of the other 32 people our office charged any less guilty? Did Russia not attack our democracy and disrupt our election with its self-described online information warfare operation? Which facts that we alleged in our various indictments — and to which many of those we indicted, including Manafort, would plead guilty — did our attackers believe were invented as a result of our alleged bias as ‘angry Democrats?’”

Mr. Trump’s allies have recently pointed with alarm to documents showing that cellphones issued to Mr. Mueller’s team were erased during the investigation; Mr. Weissmann twice entered an incorrect passcode too often, triggering a security measure that erased his phone. In an interview, he portrayed the concerns as a “tempest in a teapot” and said his understanding was that all emails and other such data from phones were backed up. He called on the Justice Department to release information about the special counsel’s data backup system.

Mr. Weissmann also wrote that he is not “anti-Trump” but rather “pro the rule of law.” Still, the distinction is less than clear in a book that also portrays Mr. Trump as a liar and a dangerous demagogue trying “to peel the world around him away from the rule of law — away from reason itself — and mold it to accommodate his desire for unchecked power.”

Mr. Weissmann was equally scathing about Attorney General William P. Barr, calling him an enabler and likening his misleading letter last spring about the then-still-secret Mueller report as a betrayal and “gut punch.”

Mr. Weissmann also criticized colleagues, portraying the special counsel team as divided between aggressive investigators like him, the F.B.I. special agent Omer Meisel and the prosecutor Jeannie Rhee — who headed “Team R,” which investigated Russian issues other than those centered on Manafort — and far more risk-averse law enforcement officials like Mr. Zebley who pulled punches.

In one episode in 2017, the Mueller team issued subpoenas to Deutsche Bank for information about Mr. Manafort’s income in Ukraine. Deutsche Bank had also lent large sums to the Trump Organization, and the White House somehow found out about the still-secret subpoenas — though not their focus. The White House demanded to know what investigators were doing, and Mr. Mueller authorized Mr. Zebley to tell the White House that they had not been seeking Mr. Trump’s financial information.

“At that point, any financial investigation of Trump was put on hold,” Mr. Weissmann writes. “That is, we backed down — the issue was simply too incendiary; the risk, too severe.”

The book provides many other examples of concessions large and small. Investigators did not try to question Mr. Trump’s daughter Ivanka — who had spoken in the lobby to a delegation of Russians who came to Trump Tower in June 2016 to meet with campaign leaders who had been promised that they were offering dirt on Hillary Clinton from the Russian government.

They “feared that hauling her in for an interview would play badly to the already antagonistic right-wing press — look how they’re roughing up the president’s daughter — and risk enraging Trump, provoking him to shut down the special counsel’s office once and for all,” he wrote.

Similarly, they did not subpoena the Trump Organization for emails about its efforts to develop a Trump-branded building in Moscow, which were active deep into the 2016 campaign.

And they did not immunize Mr. Trump’s son Donald Trump Jr., a step that would have prevented him from being able to invoke the Fifth Amendment to avoid testifying about matters like the Trump Tower meeting. Bound by grand-jury secrecy rules, Mr. Weissmann did not come out and say whether Donald Trump Jr. was threatened with or actually issued a subpoena and used his right against self-incrimination to repel it.

Mr. Weissmann laid much of the blame for what he saw as a pattern of timidity on Mr. Zebley, portraying him as a primary decision maker. “Repeatedly during our 22 months in operation, we would reach some critical juncture in our investigation only to have Aaron say that we could not take a particular action because it risked aggravating the president beyond some undefined breaking point.”

Mr. Weissmann acknowledged, but did not clearly address, concerns that the aging Mr. Mueller had lost a step, both declaring that he was capable of making the tough decisions despite “speculative concerns” about his health but also describing him in one scene as looking drained and worn down by his years of grueling public service.

While Mr. Zebley obtained Mr. Mueller’s sanction for many of his cautious directives, in one striking episode, Mr. Zebley appeared in Mr. Weissmann’s telling to have unilaterally agreed — without Mr. Mueller’s knowledge — to a request by the office of the deputy attorney general overseeing them, Rod J. Rosenstein, not to coordinate with state prosecutors “as it would undermine the president’s pardon power.”

Two other former officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, disputed the account. Mr. Rosenstein did not decline any request to share information with state prosecutors, a person familiar with his thinking wrote in an email.

Another person familiar with how the special counsel’s office interacted with Mr. Rosenstein’s office denied that there had been any agreement about sharing evidence with or withholding it from state prosecutors, and said Mr. Zebley had consulted with Mr. Mueller on every material decision.

On the failure to subpoena Mr. Trump, Mr. Mueller was determined to avoid “any public disagreements” with Mr. Rosenstein, Mr. Weissmann wrote. Because the special counsel regulations required telling Congress about any instance in which Mr. Rosenstein overruled him, Mr. Mueller never actually proposed subpoenaing Mr. Trump, instead coyly asking what Mr. Rosenstein’s reaction would be. Mr. Rosenstein just kept demurring.

In the end, Mr. Weissmann said in an interview, the caution was more justified early on to avoid provoking Mr. Trump into firing them before they could get going. But he and Ms. Rhee, among others, believed the office should have been willing to be more aggressive later on, after they had learned much of what Russia had done and had already used indictments to drag it into public view.

“We would have subpoenaed the president after he refused our accommodations, even if that risked us being fired,” he wrote. “It just didn’t sit right. We were left feeling like we had let down the American public, who were counting on us to give it our all.”

Correction: Sept. 21, 2020

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to the discussion in Andrew Weissmann's book of a business account that was used to send hush payments to an adult film star and had also received payments linked to a Russian oligarch. The information was not newly disclosed in the book; it was reported in 2018.

A version of this article appears in print on

Sept. 22, 2020

, Section A, Page 12 of the New York edition with the headline: ‘We Could Have Done More,’ Member of Mueller Team Says in New Book. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

nytimes.com

Mueller’s Team Should Have Done More to Investigate Trump-Russia Links, Top Aide Says

By Charlie Savage

12-15 minutes

A new book by one of the special counsel’s top deputies, Andrew Weissmann, is the first inside account of the investigation.

Credit...Hilary Swift for The New York Times

- Published Sept. 21, 2020Updated Sept. 22, 2020, 10:24 a.m. ET

“Had we used all available tools to uncover the truth, undeterred by the onslaught of the president’s unique powers to undermine our efforts?” wrote the former prosecutor, Andrew Weissmann, in a new book, adding, “I know the hard answer to that simple question: We could have done more.”

The team took elaborate steps to protect its files of evidence from the risk that the Justice Department might destroy them if Mr. Trump fired them and worked to keep reporters and the public from learning what they were up to, Mr. Weissmann wrote in “Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation,” which Random House will publish next week.

While he speaks reverently of Mr. Mueller, he also says his boss’s diffidence made him ill-suited for aspects of shepherding the politically charged investigation. He saw Mr. Mueller and his deputy, Aaron M. Zebley, as overly cautious.

Mr. Weissmann also defended against accusations by the president and his allies that he and other investigators were politically biased “angry Democrats”; Mr. Weissmann said his personal views had no bearing on the crimes that Russian operatives and Trump aides committed.

And he elevates particular details — for example, emphasizing that the same business account that sent hush payments to an adult film star who alleged an extramarital affair with Mr. Trump had also received “payments linked to a Russian oligarch.” The president has denied the affair; his former lawyer Michael D. Cohen controlled the account. Mr. Mueller transferred the Cohen matter to prosecutors in New York.

Previously a mafia and Enron prosecutor and then a lawyer at the F.B.I. for Mr. Mueller, who was the bureau’s director for 12 years, Mr. Weissmann ran one of three major units for the special counsel’s office. His “Team M” prosecuted Mr. Trump’s former campaign chairman Paul Manafort for numerous financial crimes. The goal was to flip him and learn whatever he knew about any Trump campaign links to Russia.

Mr. Manafort had worked for pro-Russian interests in Ukraine, and the investigation uncovered ties by his business partner, Konstantin V. Kilimnik, to Russian intelligence. The book builds toward investigators’ discovery that Mr. Manafort had shared internal campaign polling data with Mr. Kilimnik, who flew to the United States to meet with Mr. Manafort during the campaign, asking whether Mr. Trump would permit a peace plan for Russia to essentially take over all of eastern Ukraine.

But while admitting this much, Mr. Manafort — seeing the dangle of a potential pardon from Mr. Trump — refused to cooperate further. Investigators did not obtain any final puzzle pieces and lacked the evidence to charge anyone in the campaign with a criminal conspiracy involving Russia’s covert electoral assistance.

“It would seem to require significant audacity — or else, leverage — for another nation to even put such a request before a presidential candidate,” Mr. Weissmann wrote of Mr. Kilimnik’s request. “This made what we didn’t know, and still don’t know to this day, monumentally disconcerting: Namely, why would Trump ever agree to this? Why would Trump ever agree to this Russian proposal if the candidate were not getting something from Russia in return?”

Mr. Weissmann explained the significance of Mr. Manafort’s interactions with Mr. Kilimnik — also a major focus of a recent bipartisan Senate Intelligence Committee report, which explicitly labeled Mr. Kilimnik a Russian intelligence agent — more clearly than the Mueller report did.

Mr. Mueller had strictly forbidden leaks, and the special counsel team took extraordinary care to protect the high-profile, high-stakes investigation, Mr. Weissmann wrote. They kept window blind slats tilted at an angle to keep out prying eyes, shutting out natural light. They concocted an “almost comically elaborate and surreal” plan to sneak in “through the many hidden arteries of the courthouse” to obtain a grand jury indictment without tipping off reporters.

And worried about the possibility that Mr. Trump would fire them and the Justice Department would then seal off or destroy their evidence, the Mueller team members packed their numerous applications to judges for search warrants with extensive, up-to-date details about their investigation — ensuring they backed up their work beyond the reach of the executive branch.

Ty Cobb, a lawyer for Mr. Trump, also privately promised to be a “canary in the coal mine” and provide a heads up if Mr. Trump was going to fire the special counsel team, according to Mr. Weissmann. In an email, Mr. Cobb wrote that he “never made the commitment” described by Mr. Weissmann.

The investigation played out against the backdrop of regular vilification of the Mueller team by Mr. Trump and his allies like Fox News’s Sean Hannity — who turned out to be in regular contact with Mr. Manafort cooking up a “smear campaign” over text messages. Mr. Weissmann, a major target, wrote that such “ad hominem” insinuations of bias appealed to emotion rather than reason.

“I am a registered Democrat,” he wrote. “Does this make Paul Manafort or any of the other 32 people our office charged any less guilty? Did Russia not attack our democracy and disrupt our election with its self-described online information warfare operation? Which facts that we alleged in our various indictments — and to which many of those we indicted, including Manafort, would plead guilty — did our attackers believe were invented as a result of our alleged bias as ‘angry Democrats?’”

Mr. Trump’s allies have recently pointed with alarm to documents showing that cellphones issued to Mr. Mueller’s team were erased during the investigation; Mr. Weissmann twice entered an incorrect passcode too often, triggering a security measure that erased his phone. In an interview, he portrayed the concerns as a “tempest in a teapot” and said his understanding was that all emails and other such data from phones were backed up. He called on the Justice Department to release information about the special counsel’s data backup system.

Mr. Weissmann also wrote that he is not “anti-Trump” but rather “pro the rule of law.” Still, the distinction is less than clear in a book that also portrays Mr. Trump as a liar and a dangerous demagogue trying “to peel the world around him away from the rule of law — away from reason itself — and mold it to accommodate his desire for unchecked power.”

Mr. Weissmann was equally scathing about Attorney General William P. Barr, calling him an enabler and likening his misleading letter last spring about the then-still-secret Mueller report as a betrayal and “gut punch.”

Mr. Weissmann also criticized colleagues, portraying the special counsel team as divided between aggressive investigators like him, the F.B.I. special agent Omer Meisel and the prosecutor Jeannie Rhee — who headed “Team R,” which investigated Russian issues other than those centered on Manafort — and far more risk-averse law enforcement officials like Mr. Zebley who pulled punches.

In one episode in 2017, the Mueller team issued subpoenas to Deutsche Bank for information about Mr. Manafort’s income in Ukraine. Deutsche Bank had also lent large sums to the Trump Organization, and the White House somehow found out about the still-secret subpoenas — though not their focus. The White House demanded to know what investigators were doing, and Mr. Mueller authorized Mr. Zebley to tell the White House that they had not been seeking Mr. Trump’s financial information.

“At that point, any financial investigation of Trump was put on hold,” Mr. Weissmann writes. “That is, we backed down — the issue was simply too incendiary; the risk, too severe.”

The book provides many other examples of concessions large and small. Investigators did not try to question Mr. Trump’s daughter Ivanka — who had spoken in the lobby to a delegation of Russians who came to Trump Tower in June 2016 to meet with campaign leaders who had been promised that they were offering dirt on Hillary Clinton from the Russian government.

They “feared that hauling her in for an interview would play badly to the already antagonistic right-wing press — look how they’re roughing up the president’s daughter — and risk enraging Trump, provoking him to shut down the special counsel’s office once and for all,” he wrote.

Similarly, they did not subpoena the Trump Organization for emails about its efforts to develop a Trump-branded building in Moscow, which were active deep into the 2016 campaign.

And they did not immunize Mr. Trump’s son Donald Trump Jr., a step that would have prevented him from being able to invoke the Fifth Amendment to avoid testifying about matters like the Trump Tower meeting. Bound by grand-jury secrecy rules, Mr. Weissmann did not come out and say whether Donald Trump Jr. was threatened with or actually issued a subpoena and used his right against self-incrimination to repel it.

Mr. Weissmann laid much of the blame for what he saw as a pattern of timidity on Mr. Zebley, portraying him as a primary decision maker. “Repeatedly during our 22 months in operation, we would reach some critical juncture in our investigation only to have Aaron say that we could not take a particular action because it risked aggravating the president beyond some undefined breaking point.”

Mr. Weissmann acknowledged, but did not clearly address, concerns that the aging Mr. Mueller had lost a step, both declaring that he was capable of making the tough decisions despite “speculative concerns” about his health but also describing him in one scene as looking drained and worn down by his years of grueling public service.

While Mr. Zebley obtained Mr. Mueller’s sanction for many of his cautious directives, in one striking episode, Mr. Zebley appeared in Mr. Weissmann’s telling to have unilaterally agreed — without Mr. Mueller’s knowledge — to a request by the office of the deputy attorney general overseeing them, Rod J. Rosenstein, not to coordinate with state prosecutors “as it would undermine the president’s pardon power.”

Two other former officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, disputed the account. Mr. Rosenstein did not decline any request to share information with state prosecutors, a person familiar with his thinking wrote in an email.

Another person familiar with how the special counsel’s office interacted with Mr. Rosenstein’s office denied that there had been any agreement about sharing evidence with or withholding it from state prosecutors, and said Mr. Zebley had consulted with Mr. Mueller on every material decision.

On the failure to subpoena Mr. Trump, Mr. Mueller was determined to avoid “any public disagreements” with Mr. Rosenstein, Mr. Weissmann wrote. Because the special counsel regulations required telling Congress about any instance in which Mr. Rosenstein overruled him, Mr. Mueller never actually proposed subpoenaing Mr. Trump, instead coyly asking what Mr. Rosenstein’s reaction would be. Mr. Rosenstein just kept demurring.

In the end, Mr. Weissmann said in an interview, the caution was more justified early on to avoid provoking Mr. Trump into firing them before they could get going. But he and Ms. Rhee, among others, believed the office should have been willing to be more aggressive later on, after they had learned much of what Russia had done and had already used indictments to drag it into public view.

“We would have subpoenaed the president after he refused our accommodations, even if that risked us being fired,” he wrote. “It just didn’t sit right. We were left feeling like we had let down the American public, who were counting on us to give it our all.”

Correction: Sept. 21, 2020

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to the discussion in Andrew Weissmann's book of a business account that was used to send hush payments to an adult film star and had also received payments linked to a Russian oligarch. The information was not newly disclosed in the book; it was reported in 2018.

A version of this article appears in print on

Sept. 22, 2020

, Section A, Page 12 of the New York edition with the headline: ‘We Could Have Done More,’ Member of Mueller Team Says in New Book. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

- Petr Polshikov

- oleg eroshkin

- Sergei Krivov

- Andrey Malanin

- Alexander Kadakin

In Moscow Treason Trial, A Major Scandal For Russian Security Agency

Russia Finds Kaspersky Lab Cyber Experts Guilty of Treason

Last edited:

Nikulin to be sentenced in 5 days:

cyberscoop.com

Russian hacker Yevgeniy Nikulin found guilty on most serious charges after years of legal wrangling - CyberScoop

Jeff Stone

5-6 minutes

Written by

Jul 10, 2020 | CYBERSCOOP

A U.S. jury has found an accused Russian hacker guilty on charges that he hacked LinkedIn and Formspring in a pair of 2012 data breaches in which he stole credentials belonging to more than 100 million Americans.

Yevgeniy Nikulin was found guilty after just hours of deliberation, roughly eight years after he first infiltrated the U.S. social media companies in a successful attempt to steal data about American web users. He also was found guilty of trafficking Formspring data, and damaging a computer belonging to a Formspring employee in excess of $5,000.

“Nikulin’s conviction is a direct threat to would-be hackers, wherever they may be,” U.S. Attorney David Anderson said in a statement. “Computer hacking is not just a crime, it is a direct threat to the security and privacy of Americans. American law enforcement will respond to that threat regardless of where it originates.”

Nikulin was charged in 2016 with nine felony counts, including computer intrusion and aggravated identity theft, in connection with data breaches that occurred in 2012 at LinkedIn and Formspring. Nikulin was accused of stealing roughly 117 million usernames and passwords, then trying to sell those credentials to other users on Russian-language forums used primarily for cybercrime.

Unlike more typical computer crime cases, the Nikulin prosecution has spotlighted how an earlier generation of alleged internet scammers hacked American companies, sometimes with direct knowledge of Russian intelligence services, the Justice Department has alleged.

Prosecutors had argued that Nikulin operated as the digital equivalent of a common thief, using hacking tools to steal a database of sensitive information and then trying to sell it to fraudsters. The defense suggested that investigators could not definitively tie Nikulin to an internet alias, search history and other digital forensics that U.S. attorneys introduced as evidence. At one point, defense attorney Adam Gasner said anyone, including Russian intelligence agencies, could have used Nikulin’s email accounts to commit crimes in his name.

Through the trial, Judge William Alsup also questioned the prosecution’s evidence, telling U.S. Attorney Michelle Kane that the material was so dull that she risked boring the jury. The trial was suspended for three months amid the coronavirus pandemic, requiring the replacement of multiple jurors.

Nikulin, now 32, was arrested in 2016 by authorities in the Czech Republic as part of an Federal Bureau of Investigation operation. He was incarcerated there for two years while Czech officials weighed competing extradition requests from the U.S. and Russia, which had alleged that American police were “hunting for Russian citizens” around the globe.

Justice Department prosecutors also have tied Nikulin to a ring of hackers, data brokers and spies who were operating in and around Moscow in 2012. According to the government, Nikulin was in talks with an accused scammer, Nikita Kislitsin, about selling the data he stole from LinkedIn, a relationship brokered by another man who was an asset of the Russian security services. A court filing made public in March identified Nikulin, Kislitin and a number of other accused cybercriminals as being present at a meeting at a Russian hotel, where attendees discussed starting a business.

Nikulin, though, was one of a handful of indicted Russian men actually extradited to the U.S. in recent years amid mounting opposition from the Kremlin.

Upon his arrival in the U.S., Nikulin refused to cooperate with his defense counsel and met with Russian government officials without a lawyer present, according to his former attorney. Nikulin also was placed in solitary confinement for allegedly vandalized his jail cell and physically attacking corrections officers in the Santa Rita jail in California. He ultimately was deemed competent to stand trial after a psychiatric evaluation.

The verdict comes after a mistrial in the unrelated case of Joshua Schulte, a former CIA software engineer accused of leaking classified U.S. hacking tools to WikiLeaks. The prosecution’s failure to convict Schulte on the most serious charges in such a widely watched case had raised questions about whether the government could effectively communicate the often dense technical information to jurors unfamiliar with the matter.

Nikulin’s sentencing is scheduled for September 29.

cyberscoop.com

Russian hacker Yevgeniy Nikulin found guilty on most serious charges after years of legal wrangling - CyberScoop

Jeff Stone

5-6 minutes

Written by

Jul 10, 2020 | CYBERSCOOP

A U.S. jury has found an accused Russian hacker guilty on charges that he hacked LinkedIn and Formspring in a pair of 2012 data breaches in which he stole credentials belonging to more than 100 million Americans.

Yevgeniy Nikulin was found guilty after just hours of deliberation, roughly eight years after he first infiltrated the U.S. social media companies in a successful attempt to steal data about American web users. He also was found guilty of trafficking Formspring data, and damaging a computer belonging to a Formspring employee in excess of $5,000.

“Nikulin’s conviction is a direct threat to would-be hackers, wherever they may be,” U.S. Attorney David Anderson said in a statement. “Computer hacking is not just a crime, it is a direct threat to the security and privacy of Americans. American law enforcement will respond to that threat regardless of where it originates.”

Nikulin was charged in 2016 with nine felony counts, including computer intrusion and aggravated identity theft, in connection with data breaches that occurred in 2012 at LinkedIn and Formspring. Nikulin was accused of stealing roughly 117 million usernames and passwords, then trying to sell those credentials to other users on Russian-language forums used primarily for cybercrime.

Unlike more typical computer crime cases, the Nikulin prosecution has spotlighted how an earlier generation of alleged internet scammers hacked American companies, sometimes with direct knowledge of Russian intelligence services, the Justice Department has alleged.

Prosecutors had argued that Nikulin operated as the digital equivalent of a common thief, using hacking tools to steal a database of sensitive information and then trying to sell it to fraudsters. The defense suggested that investigators could not definitively tie Nikulin to an internet alias, search history and other digital forensics that U.S. attorneys introduced as evidence. At one point, defense attorney Adam Gasner said anyone, including Russian intelligence agencies, could have used Nikulin’s email accounts to commit crimes in his name.

Through the trial, Judge William Alsup also questioned the prosecution’s evidence, telling U.S. Attorney Michelle Kane that the material was so dull that she risked boring the jury. The trial was suspended for three months amid the coronavirus pandemic, requiring the replacement of multiple jurors.

Nikulin, now 32, was arrested in 2016 by authorities in the Czech Republic as part of an Federal Bureau of Investigation operation. He was incarcerated there for two years while Czech officials weighed competing extradition requests from the U.S. and Russia, which had alleged that American police were “hunting for Russian citizens” around the globe.

Justice Department prosecutors also have tied Nikulin to a ring of hackers, data brokers and spies who were operating in and around Moscow in 2012. According to the government, Nikulin was in talks with an accused scammer, Nikita Kislitsin, about selling the data he stole from LinkedIn, a relationship brokered by another man who was an asset of the Russian security services. A court filing made public in March identified Nikulin, Kislitin and a number of other accused cybercriminals as being present at a meeting at a Russian hotel, where attendees discussed starting a business.

Nikulin, though, was one of a handful of indicted Russian men actually extradited to the U.S. in recent years amid mounting opposition from the Kremlin.