From January through April 2008, the Party of Regions mounted a slick, well-coordinated campaign against Ukraine's NATO membership. The "NATO No" slogan appeared on giant television screens and mass-produced blue signs at rallies where Yanukovych spoke. The same slogan was emblazoned on blue and yellow signs carried by the party's members of Parliament onto the floor of the Parliament in February.

Provided with examples of the messaging, Manafort's spokesman declined to comment.

In 2010, Yanukovych ran for president again, and Manafort again worked for him. This time, Yanukovych pledged to end Ukraine's NATO bid. Ukraine should not be a member of any military bloc, he said, because "this is the view of the Ukrainian people." During a meeting with the U.S. ambassador, he said he wanted to "improve cooperation with the U.S. and NATO, but was also interested in

"restoring" relations with Russia.

He was elected president, and this time turned East for good.

"Either Manafort was wrong about his guy, or he just didn't care," said Dan Fried, a former assistant secretary of state for the region under George W. Bush and Obama. "I think Manafort would've preferred his guy be the guy he said he was, but he was okay if he wasn't. He was doing a job for a client. That's it."

A year into Yanukovych's presidency, his administration prosecuted his chief political rival, former

"Orange" Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, for allegedly abusing her position during her time in office. She was sentenced to seven years in prison. Many international observers condemned the prosecution as politically motivated.

Former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, left, and her husband Oleksandr exit booths at a polling station during parliamentary elections in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine on October 26, 2014. Alexander Pokopenko / AP file

Manafort again looked to the U.S. to burnish his client's image, and dispel charges that Yanukovych was a corrupt, pro-Putin autocrat. He arranged for Yanukovych's administration to hire the law firm Skadden Arps to do a legal review of the prosecution. The resulting brief pointed out some serious procedural flaws, but was largely approving of the Ukrainian court.

Around the same time, however, the Yanukovych administration began to strengthen its ties to the Putin regime and to further Russify the Party of Regions.

According to Inna Bohoslovska, who was a Party of Regions-aligned member of parliament at the time, starting in 2012, "[Ethnically] Russian candidates were placed in all the strong positions. Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Security Service."

Yanukovych then reversed his position on integrating Ukraine with Europe. Ukraine was about to sign an EU association agreement, making its turn away from Russia and towards the West official, when Yanukovych backed out a week before an official signing ceremony.

A protester throws a molotov cocktail at riot police in the center of Kiev on Jan. 22, 2014, as clashes continued following two months of protests over President Viktor Yanukovych's failure to sign a deal for closer ties with the EU. VASILY MAXIMOV / AFP - Getty Images

Said Fried, "[Yanukovych] broke more than a campaign promise, he broke his compact with the Ukrainian people."

Yanukovych's popularity plummeted. His EU decision ignited massive demonstrations in the streets of Kiev, with some crowds as big as 1 million. Ukrainian police cracked down on protestors, and both police and protestors were killed in street violence that took at least 100 lives.

After three months of demonstrations, Yanukovych was ousted as president in February 2014. He fled to Russia. Activists broke into Mezhyhirya, his ornate presidential palace, and

were outraged by its gold-plated opulence. "[Manafort] knew that the president's salary was not enough for the luxury of the Mezhyhirya, so he should have been aware that it was anything but legal money," said a top Ukrainian anti-corruption investigator.

President Viktor Yanukovych's palatial residence outside Kiev on Feb, 22, 2014 after Yanukovych had fled east.Efrem Lukatsky / AP

"If you're going to work for someone like Yanukovych," said Fried, "there's a time to jump ship, and that's when he starts shooting people."

Manafort returned to Ukraine after Yanukovych fled the country. He tried, with limited success, to help remnants of the Party of Regions regain power in the October 2014 parliamentary elections.

Yanukovych remains in Russia. He has been sanctioned by the EU and the U.S. for the Crimea invasion, and is wanted by Ukraine for a long list of charges that have included corruption and murder.

"Yanukovych was so awful," said Fried. "That's not Manafort's fault, but the fact that Manafort helped Yanukovych win an election didn't do Ukraine any good."

Who Paid The Bills?

Manafort says the 2014 election was his last in Ukraine, and he is done with Ukrainian politics.

But he is now facing questions from Congress and federal investigators about how he was paid for his political work, what he did with the money he earned, and what other business relationships he developed while in Ukraine.

A Party of Regions accounting book, dubbed the "black ledger" and obtained in August by Ukraine's National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU), allegedly shows that Manafort was paid $12.7 million in cash by the party between Nov. 2007 and Oct. 2012.

The ledger records what Ukrainian investigators say were off-the-books payments by the Party of Regions to election officials, party functionaries, and members of parliament. Manafort appears as an intended recipient in the ledger 22 times from 2007 until 2012, according to the NABU. The Bureau notes that the entries are not themselves proof that the payments were made.

In March, journalist Serhiy Leshchenko made waves when he said he had obtained an invoice on Manafort company letterhead detailing how Manafort received money from a shell company in Belize for the alleged sale of 500 computers.

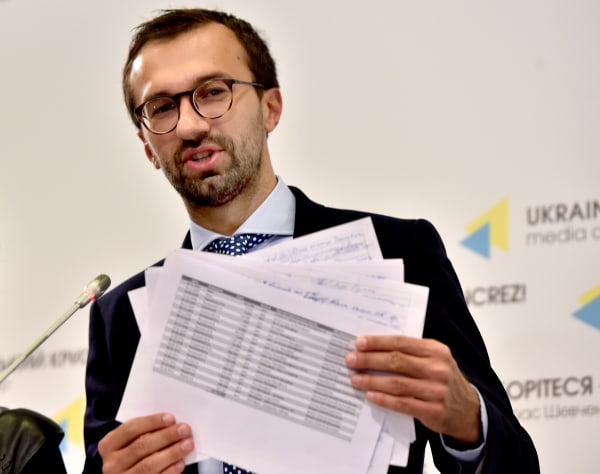

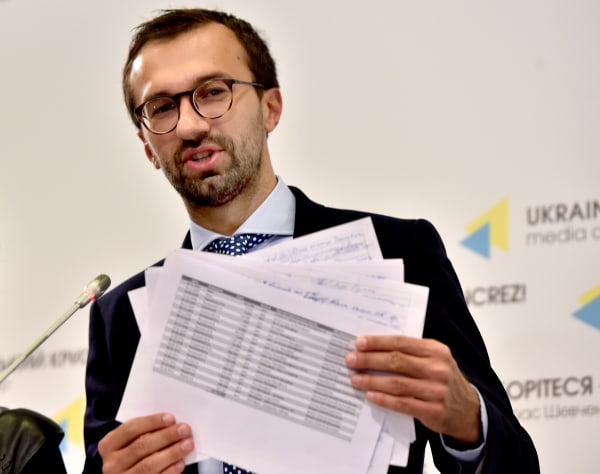

Ukrainian journalist and member of parliament Serhiy Leshchenko holds pages showing alleged payments to Paul Manafort from an accounting book of the party of former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych during a press conference in Kiev on Aug. 19, 2016. Sergei Supinsky / AFP-Getty Images

The date on the invoice and the amount of money match an entry in the black ledger marked "Manafort." Manafort's spokesman dismissed the invoice and letterhead as fabricated. The shell company, Neocom Systems Ltd., was registered with Belize's International Business Company Registry, but the principal of the firm that registered the shell company told NBC News he had only dealt with its lawyers, and couldn't provide any information about its owners. It was struck from the registry in 2011 and dissolved in 2014, according to the Belizean registry.

Manafort has described the ledger as a forgery. He says any payments he received from Ukraine were legitimate compensation for his work as a consultant, and the payments were lawfully wired to him.

Manafort's spokesman told NBC News that Manafort "has no knowledge of any payment ledger. Mr. Manafort was only paid via wire — not cash — through U.S. institutions, typically using clients' preferred financial institutions and instructions."

The spokesman said Manafort declined to answer whether he had reported to the U.S. government all money and income received from Ukraine.

Ukrainian investigators told NBC News they are now looking into Manafort's role in the Skadden deal, but say Manafort is not a suspect in any of their investigations.

Manafort also did business with several Ukrainian and Russian oligarchs.

In 2008, Manafort and his real estate partners courted a Ukrainian oligarch named Dmytro Firtash, a major Party of Regions backer, in an $850 million plan to redevelop a famous New York hotel, the Drake. The plan never bore fruit.

Firtash, who acknowledged to the U.S. ambassador that he got his start in business with the permission of a Russian crime lord,

according to a leaked cable, is under federal indictment in the Northern District of Illinois for bribery. He is under arrest in Austria pending his extradition to the U.S.

In 2007, Manafort went into business with Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska to invest in Ukrainian and European assets. Manafort's partner Rick Gates "regularly visited" the Moscow offices of Deripaska's representatives to discuss the investments, according to a later lawsuit.

In 2007 and 2008, companies controlled by Deripaska paid $26.25 million in investment capital and management fees to Manafort and his partners for a deal to buy a cable television company in Ukraine, according to a U.S. court filing. According to Manafort's spokesman, all the capital was paid to the seller of the company, but Deripaska's legal representatives alleged the investment was never actually made.

By 2014, Manafort and Deripaska had fallen out over the cable deal, which never materialized.

What did Manafort do with his Ukrainian millions?

He was associated with

at least 15 bank accounts and 10 companies on Cyprus, dating back to 2007, according to two banking sources with direct knowledge.

Related: Manafort-Linked Accounts on Cyprus Raised Red Flags

The sources told NBC News' Richard Engel that after certain transactions raised concern, the bank began investigating the accounts for possible money-laundering. Manafort closed some of the accounts in 2012.

A spokesman for Manafort told NBC News that all the accounts were set up at the direction of clients in Cyprus, a common banking center for Russians and Ukrainians, "for a legitimate business purpose."

As NBC News and others previously reported, Manafort also

bought four properties in New York City between 2006 and 2013, apparently for cash, and then took out more than $15 million in loans on them between 2015 and 2017.

Related: Ex-Trump Aide Manafort Bought New York Homes With Cash

A source familiar with the matter said New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman is taking "a preliminary look" at Manafort's real estate transactions.

Manafort said his transactions were "executed in a transparent fashion and my identity was disclosed — in fact my name is right there on the documents."

In September 2016, NBC News has reported Manafort took out a mortgage on his home in Bridgehampton, New York, but no mortgage notice was ever filed and no mortgage tax paid, according to Suffolk County records. His name did not appear on any publicly available documents.

Related: Feds Subpoena Records for $3.5 Million Mystery Mortgage on Manafort Home

A spokesperson for Manafort said the mortgage was a bridge loan and was paid off by December. Manafort's lawyer said the mortgage paperwork was rejected because of an error and was never refiled.

Federal investigators

have now subpoenaed records related to that loan.

Kenzi Abou-Sabe

Tom Winter

Max Tucker

First Published Jun 27 2017, 6:13 am ET

I used to scan my computer with their online scanner. For a hot minute, this was the go to online scanner on many malware removal forums.