SEX AND THE SUGAR DADDY

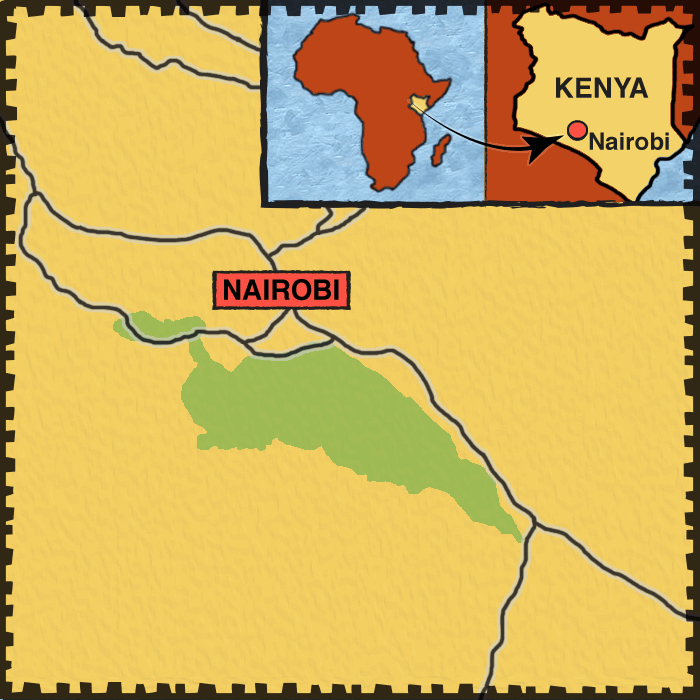

In Kenya, more and more young women are using sugar daddies to fund a lifestyle worth posting on social media.

Transactional sex was once driven by poverty, says film-maker Nyasha Kadandara. But now, increasingly, it's driven by vanity.

(Warning: Contains adult themes and graphic images)

Eva, a 19-year-old student at Nairobi Aviation College, was sitting in her tiny room in shared quarters in Kitengela feeling broke, hungry, and desperate. She used the remaining 100 Kenyan shillings she had in her wallet and took a bus to the city centre, where she looked for the first man who would pay to have sex with her. After 10 minutes in a dingy alley, Eva went back to Kitengela with 1,000 Kenyan shillings to feed herself for the rest of the month.

Six years ago, when she was at university, Shiro met a married man nearly 40 years her senior. At first, she received just groceries. Then it was trips to the salon. Two years into their relationship, the man moved her into a new apartment because he wanted her to be more comfortable. Another two years down the line, he gave Shiro a plot of land in Nyeri county as a show of commitment. In exchange, he gets to sleep with Shiro whenever he feels like it.

Eva's experience is transactional sex in its most unvarnished form - a hurried one-off encounter, driven by desperation. Shiro's story illustrates an altogether more complex phenomenon - the exchange of youth and beauty for long-term financial gain, motivated not by hunger but by aspiration, glamorised by social media stars, and often wrapped in the trappings of a relationship.

Older men have always used gifts, status, and influence to buy access to young women. The sugar daddy has probably been around, in every society, for as long as the prostitute. So you might ask: "Why even have a conversation about transactional sex in Africa?"

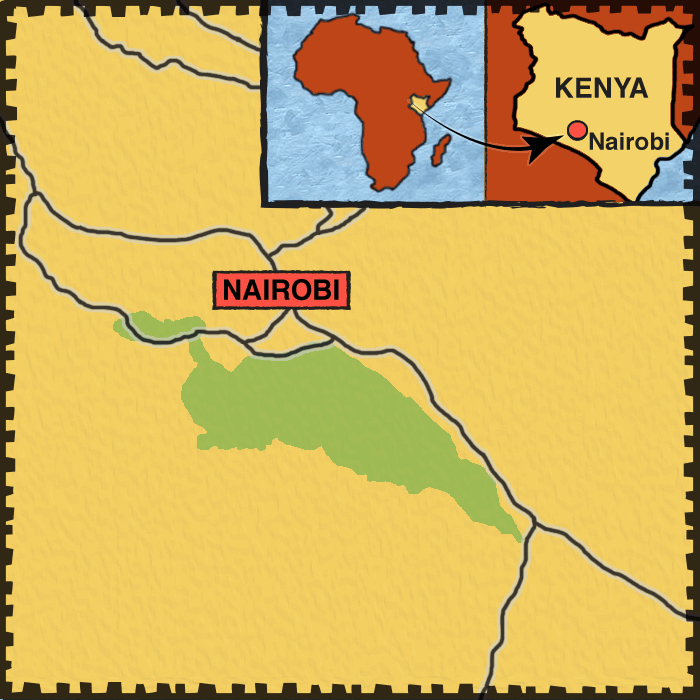

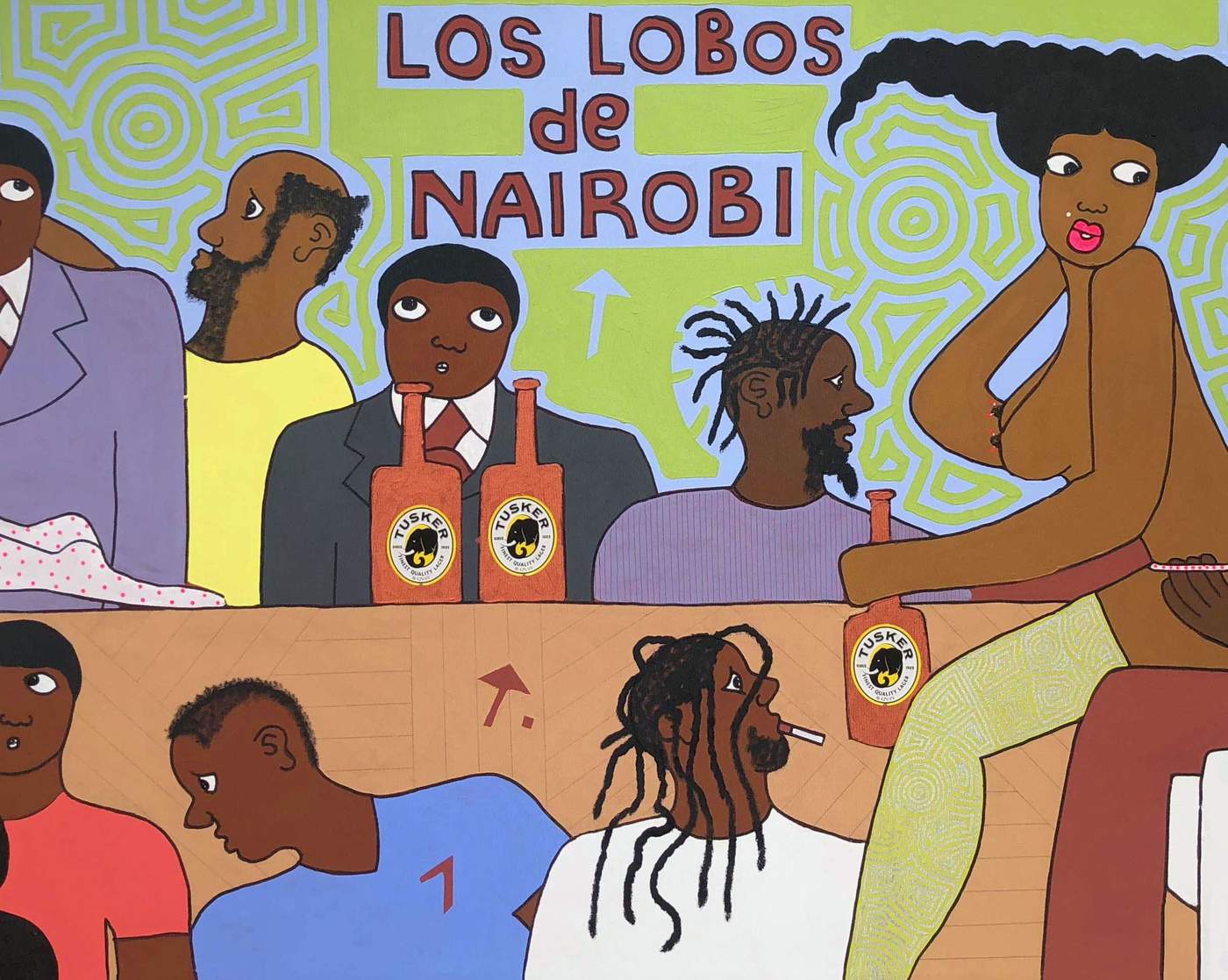

The answer is that in Kenya, and in some other African countries, "sugar" relationships seem to have become both more common and more visible: what once was hidden is now out in the open - on campuses, in bars, and all over Instagram.

Exactly when this happened is hard to say. It could've been in 2007 when Kim Kardashian's infamous sex tape was leaked, or a little later when Facebook and Instagram took over the world, or perhaps when 3G internet hit Africa's mobile phones.

But somehow, we have arrived at a point where having a "sponsor" or a "blesser" - the terms that millennials usually apply to their benefactors - has for many young people become an accepted, and even a glamorous lifestyle choice.

You only have to visit the student districts of Nairobi, one recent graduate told the BBC, to see how pervasive the sponsor culture has become. "On a Friday night just go sit outside Box House [student hostel] and the see what kind of cars drive by - drivers of ministers, and politicians sent to pick up young girls," says Silas Nyanchwani, who studied at the University of Nairobi.

Until recently there was no data to indicate how many young Kenyan women are involved in sugar relationships. But this year the Busara Centre for Behavioural Economics conducted a study for BBC Africa in which they questioned 252 female university students between the ages of 18 and 24. They found that approximately 20% of the young women who participated in the research has or has had a "sponsor."

The sample size was small and the study was not fully randomised, so the results only give an indication of the possible numbers, they cannot be taken as definitive. Also, only a small percentage openly admitted to having a sugar daddy; the researchers were able to infer that a number were hiding the truth from answers they gave to other questions, using a technique called list randomisation. But interestingly, when talking about others, not about themselves, the young women estimated on average that 24% of their peers had engaged in a transactional sexual relationship with an older man - a figure very close to that reached by the researchers

THE STUDENT

Jane, a 20-year-old Kenyan undergraduate who readily admits to having two sponsors, sees nothing shameful in such relationships - they are just part of the everyday hustle that it takes to survive in Nairobi, she says.

She also insists that her relationships with Tom and Jeff, both married, involve friendship and intimacy as well as financial exchange.

"They help you sometimes, but it's not always about sex. It's like they just want company, they want someone to talk to," she says.

She says that her religious parents brought her up with traditional values, but she has made her own choices. One of her motives, she says, is to be able to support her younger sisters, so they won't need to rely on men for money. But she has also been inspired by Kenya's celebrity "socialites" - women who have transformed sex appeal into wealth, becoming stars of social media.

Among them are the stars of the reality TV show Nairobi Diaries, Kenya's own blend of Keeping up with the Kardashians and The Real Housewives of Atlanta. The show has launched several socialites out of Nairobi's slums and on to yachts off the coast of Malibu or the Mediterranean.

"Nairobi Diaries is like the Kardashians playing out [on screen] in real time. If I look hot, I look good, there has got be some rich guy who will pay good money to possess me," says Oyunga Pala, Nairobi columnist and social commentator.

The best known of the Kenyan socialites is probably Vera Sidika, who went from dancing in music videos on to the set of the Nairobi Diaries, and from there launched a business career based on her fame and her physique.

"My body is my business - and it is a money maker," she said back in 2014, when discussing her controversial skin-lightening procedures. Nowadays, Vera is keen to promote herself as an entrepreneur, and runs a successful brand of "detox" herbal infusions called Veetox Tea.

Equally famous is model and socialite Huddah Monroe, who also rose to fame on reality TV - in her case Big Brother Africa, in 2013 - and who now runs a well-established line of cosmetics. "If you have to expose your body, make money out of it," she was reported as saying, referring to the semi-nude images that she shows off to her 1.3 million Instagram followers.

In the past, some of Kenya's socialites have styled themselves as #SlayQueens, and have been quite upfront about the financial benefits that have come from dating tyc00ns. Having made it to the top, though, they often begin to cultivate a different image - presenting themselves as independent, self-made businesswomen and encouraging Kenyan girls to work hard and stay in school.

The millions of fans scrolling through their Instagram posts, though, are not blind. The sudden emphasis on entrepreneurship does not hide the fact that these women used their sex appeal to create opportunities in the first place. And many - quite understandably - are attempting to apply this methodology to their own lives.

In Kenya, more and more young women are using sugar daddies to fund a lifestyle worth posting on social media.

Transactional sex was once driven by poverty, says film-maker Nyasha Kadandara. But now, increasingly, it's driven by vanity.

(Warning: Contains adult themes and graphic images)

Eva, a 19-year-old student at Nairobi Aviation College, was sitting in her tiny room in shared quarters in Kitengela feeling broke, hungry, and desperate. She used the remaining 100 Kenyan shillings she had in her wallet and took a bus to the city centre, where she looked for the first man who would pay to have sex with her. After 10 minutes in a dingy alley, Eva went back to Kitengela with 1,000 Kenyan shillings to feed herself for the rest of the month.

Six years ago, when she was at university, Shiro met a married man nearly 40 years her senior. At first, she received just groceries. Then it was trips to the salon. Two years into their relationship, the man moved her into a new apartment because he wanted her to be more comfortable. Another two years down the line, he gave Shiro a plot of land in Nyeri county as a show of commitment. In exchange, he gets to sleep with Shiro whenever he feels like it.

Eva's experience is transactional sex in its most unvarnished form - a hurried one-off encounter, driven by desperation. Shiro's story illustrates an altogether more complex phenomenon - the exchange of youth and beauty for long-term financial gain, motivated not by hunger but by aspiration, glamorised by social media stars, and often wrapped in the trappings of a relationship.

Older men have always used gifts, status, and influence to buy access to young women. The sugar daddy has probably been around, in every society, for as long as the prostitute. So you might ask: "Why even have a conversation about transactional sex in Africa?"

The answer is that in Kenya, and in some other African countries, "sugar" relationships seem to have become both more common and more visible: what once was hidden is now out in the open - on campuses, in bars, and all over Instagram.

Exactly when this happened is hard to say. It could've been in 2007 when Kim Kardashian's infamous sex tape was leaked, or a little later when Facebook and Instagram took over the world, or perhaps when 3G internet hit Africa's mobile phones.

But somehow, we have arrived at a point where having a "sponsor" or a "blesser" - the terms that millennials usually apply to their benefactors - has for many young people become an accepted, and even a glamorous lifestyle choice.

You only have to visit the student districts of Nairobi, one recent graduate told the BBC, to see how pervasive the sponsor culture has become. "On a Friday night just go sit outside Box House [student hostel] and the see what kind of cars drive by - drivers of ministers, and politicians sent to pick up young girls," says Silas Nyanchwani, who studied at the University of Nairobi.

Until recently there was no data to indicate how many young Kenyan women are involved in sugar relationships. But this year the Busara Centre for Behavioural Economics conducted a study for BBC Africa in which they questioned 252 female university students between the ages of 18 and 24. They found that approximately 20% of the young women who participated in the research has or has had a "sponsor."

The sample size was small and the study was not fully randomised, so the results only give an indication of the possible numbers, they cannot be taken as definitive. Also, only a small percentage openly admitted to having a sugar daddy; the researchers were able to infer that a number were hiding the truth from answers they gave to other questions, using a technique called list randomisation. But interestingly, when talking about others, not about themselves, the young women estimated on average that 24% of their peers had engaged in a transactional sexual relationship with an older man - a figure very close to that reached by the researchers

THE STUDENT

Jane, a 20-year-old Kenyan undergraduate who readily admits to having two sponsors, sees nothing shameful in such relationships - they are just part of the everyday hustle that it takes to survive in Nairobi, she says.

She also insists that her relationships with Tom and Jeff, both married, involve friendship and intimacy as well as financial exchange.

"They help you sometimes, but it's not always about sex. It's like they just want company, they want someone to talk to," she says.

She says that her religious parents brought her up with traditional values, but she has made her own choices. One of her motives, she says, is to be able to support her younger sisters, so they won't need to rely on men for money. But she has also been inspired by Kenya's celebrity "socialites" - women who have transformed sex appeal into wealth, becoming stars of social media.

Among them are the stars of the reality TV show Nairobi Diaries, Kenya's own blend of Keeping up with the Kardashians and The Real Housewives of Atlanta. The show has launched several socialites out of Nairobi's slums and on to yachts off the coast of Malibu or the Mediterranean.

"Nairobi Diaries is like the Kardashians playing out [on screen] in real time. If I look hot, I look good, there has got be some rich guy who will pay good money to possess me," says Oyunga Pala, Nairobi columnist and social commentator.

The best known of the Kenyan socialites is probably Vera Sidika, who went from dancing in music videos on to the set of the Nairobi Diaries, and from there launched a business career based on her fame and her physique.

"My body is my business - and it is a money maker," she said back in 2014, when discussing her controversial skin-lightening procedures. Nowadays, Vera is keen to promote herself as an entrepreneur, and runs a successful brand of "detox" herbal infusions called Veetox Tea.

Equally famous is model and socialite Huddah Monroe, who also rose to fame on reality TV - in her case Big Brother Africa, in 2013 - and who now runs a well-established line of cosmetics. "If you have to expose your body, make money out of it," she was reported as saying, referring to the semi-nude images that she shows off to her 1.3 million Instagram followers.

In the past, some of Kenya's socialites have styled themselves as #SlayQueens, and have been quite upfront about the financial benefits that have come from dating tyc00ns. Having made it to the top, though, they often begin to cultivate a different image - presenting themselves as independent, self-made businesswomen and encouraging Kenyan girls to work hard and stay in school.

The millions of fans scrolling through their Instagram posts, though, are not blind. The sudden emphasis on entrepreneurship does not hide the fact that these women used their sex appeal to create opportunities in the first place. And many - quite understandably - are attempting to apply this methodology to their own lives.

You are nikka......I've assigned you paragraph 2

You are nikka......I've assigned you paragraph 2 and their boyfriend is cool w/ it??

and their boyfriend is cool w/ it??