Rapmastermind

Superstar

March 9th will be a day that lives in Hip Hop Infamy forever as that’s the day we lost the great Christopher Wallace. Canibus made the date even more Iconic with his Legendary bars on “2nd Round K.O.” But another date also holds that significance. September 13th has become one of the most famous dates in the history of Hip Hop. It’s the day that Iconic Rap Legend Tupac Shukar died from his gunshot wounds from the Las Vegas Shooting. This year in 2014 we celebrate the 18th Anniversary of his passing. Ironically this date is another Anniversary.

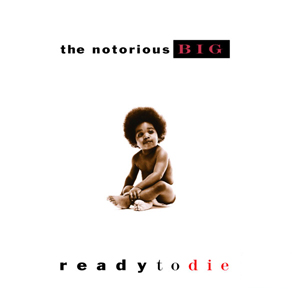

2 Years before Pac’s death, an up and coming underground emcee from Brooklyn New York unleashed his debut album on the world. “Ready To Die” was released September 13th 1994 and Hip Hop has never been the same sense. This thread is give a full history on the lead up to the album. It also features the amazing XXL “Making of Ready To Die” and why 20 years later it can be debated as the greatest rap album of all time.

(At a young Age Biggie proved to be gifted and a natural rapper and emcee)\

"Considered a Fool cause I dropped out of High School, Stereotypes of black male misunderstood, but it's still all good" - Juicy

*READY TO SUCCEED: Biggie was an underground Legend before Puffy even met him. Rapping on Video Music Box as a teen to Battling cats on the corner. The streets of Brooklyn knew Christopher before anyone else did. But it was Big Daddy Kane’s DJ Mister Cee and DJ 50 Grand that got the ball rolling for Big. After Matty C got the Biggie Demo and featured it in the Source Unsigned Hype. He got a call from Puffy looking for new artist. Matty then passed on Big’s demo to Puff and the rest is history. Biggie meanwhile was on the streets selling drugs still after being kicked out of his mother’s house.

(In the beginning Biggie did use to write lyrics down but during the "Ready To Die" recording process he learned to memorize his bars in his head. This technique is now being used by many popular rappers in the game)

"I'm doing rhymes now, F*ck the crimes now, Out on the Ave, I'm real hard to find now, cause I'm knee deep in the beats" - Machine Gun Funk

*READY TO RECORD: After Big’s demo was a hit it was time for him to get in the studio and put some songs on wax. Biggie was originally signed to Uptown but Puffy was fired and he was in limbo. He did record almost Half of "Ready To Die" while on Uptown. He was still selling drugs cause “Nicks move for 20’s down south” and ended up getting locked up in North Carolina and did a 9 month bid. While behind bars he decided he would pursue his rap career full time. Once Puffy got his Bad Boy Label everything changed. Biggie’s earliest solo recording on record is the underground cut “Biggie got the Hype Sh!t”.

He would follow that up with a series of collabos starting with a feature with Aaron Hall called “Why you trying to play me” where he was credited as “Christopher Wallace”. By 93 he would release his very 1st single on the “Who’s The Man” Soundtrack called “Party and Bullshyt”. That song got the streets hot but didn’t perform on the charts. Biggie also appeared on title track of the soundtrack “Who’s the Man”. His 1st album feature came on Heavy D’s “Blue Funk” on the track called “A Bunch of N!ggas” which featured Guru and Busta Rhymes as well.

Next thing you know artist were contacting Biggie to get on remixes and that proved to be a success. He got on a remix for Neneh Cherry’s “Buddy X”. He would finally enter the charts when he was featured on the remix to Super Cat’s “Dolly My Baby” which was his 1st Hot 100 appearance. He followed that up with the remix to the Mary J Blige Classic “Real Love”. By the end of 1993 Biggie was one of the hottest underground rappers in New York. During this time he got the attention of another New York born Emcee by the name of Tupac Shakur who took him on shows and even recorded with him. "Flava in Ya Ear" Remix also fueled the buzz for Biggie's debut as his verse is considered the most memorable on the posse cut.

(The Westcoast dominated Hip Hop Critically and Commercially until "Ready To Die" brought the final shift)

"Your Face, My Feet, They Meet, With Stomping, I'm Ripping Emcees, From Tallahassee to Compton" - Machine Gun Funk

*READY TO COMPETE: “The Chronic” and “Doggystyle” were still burning up Hip Hop Airwaves and charts. On the Eastcoast there were a few groups still selling but there was no dominate New York act that could compete with The West Coast. By the time 1994 rolled around New York had dropped Masterpiece’s from both Wu Tang and NaS with “36 Chambers” and “ILLmatic”.

Wu’s album was able to go Platinum within a year and propel them as one of Hip Hop best new groups. NaS “ILLmatic” got the critical acclaim but wasn’t able to have the same commercial success. Quality wasn’t an issue for New York at the time as many rappers and groups dropped great albums. It was sales. No Eastcoast album could compete with Dre and Snoop. Then out of nowhere came other hit West Coast album with Warren G’s “Regulate”. By this point it seemed the West Reign on the Top was never going to end. That was until a certain Single dropped.

(Biggie climbed the ladder to success escalator style after his debut came out)

"Put the drugs on the shelf, knaw couldn't see it. SCARFACE, KING OF NEW YORK, I wanna BE IT" - RESPECT

*READY TO TAKEOVER: “Juicy” was released on August 8th 1994. The song was an INSTANT Hit burning up the charts and radio not just in New York but all over the country. The single had a sample from the Classic RnB song “Juicy Fruit” by Mtume. It was a rags to riches story about Big’s life from street corners to interviews by the pool. The song felt autobiographical. With Pop Culture references and shout outs to Hip Hop DJ’s and Pioneers. Biggie made a single everyone could enjoy. The Single was a success going Gold and by the time the album was released it had set the streets and the charts on fire.

Within 2 Months the album was Gold, with in 6 months it was Platinum. By 1995 it was multi-Platinum. “Juicy” got the fire started but “Big Poppa” took Biggie even further up the charts. The Overweight Lover anthem with the Classic Isley Brother’s sample set clubs ablaze and took Biggie from a regional New York Underground Act to a Pop Sensation. The song ended being a Top 10 hit for Biggie and went Platinum. It earned Biggie his 1st Grammy nomination. The last single from the album ended up making history. The Remix for “One More Chance” tied Michael and Janet Jackson’s “Scream” as the highest debut for a single in History breaking The Beatles record. The single ended going Platinum and earned Biggie two Billboard Awards for Biggie Rap single and Artist of the year.

(Before Biggie called himself "The Hitchcock of Hip Hop" he proved his storytelling abilities on his debut. HIs name Biggie Smalls is from the Film "Let's Do It Again". His alter ego Frank White is the name of the character from "King of New York". Biggie love movies and you could tell in his storytelling. Ironically one of Hitchcock's best and famous films was called "Notorious")

"I know how it feels to wake up f*cked up. Pockets broke as hell another rock to sell. People look at you like you the loser selling drugs to all the users mad buddah abusers" - EVERYDAY STRUGGLE

*READY TO TELL A STORY: What made “Ready To Die” work was the fact it plays out like an audio movie. You could literally “SEE” Biggie’s words in your mind. From the beginning of the album “Intro” Biggie was in Storytelling mode as it starts from his birth. The baby on the album cover actually symbolizes Biggie‘s birth, through his teens up until his prison sentence. As he’s leaving Jail you hear a Snoop Dogg Classic “Da Shizit” playing in the back. As the 1 song “Things Dun Changed” began you hear a sample from “The Chronic” “Lil Ghetto Boy”. It was if Biggie was subconsciously or consciously telling us there’s a New Sherrif in town after the West’s Dominance.

He even ended the Intro with “I got Big Plans”. The album then goes on to give you stories like “Gimmie The Loot”, “Warning” and “Me and My B!tch”. Even on songs that weren’t stories Big always told them in story form. “Everyday Struggle” is a story of the trails and tribulations of the Drug Game. “Respect” Biggie gives us a 3 act story about his life before and after birth. Even “One More Chance” is a story of Biggie’s sexual exploits. To accent the audio movie concept even more is the fact the album ends with the haunting “Suicidal Thoughts”. You really felt Puffy was terrified on the other line and the “THUMP” at the end accepts that shot himself. “Ready To Die” isn’t just a Classic album cause of the great rhymes, production and songs but because it told a cohesive story. In that story Biggie explained that this lifestyle has two endings. Dead - Suicidal Thoughts or In Jail - The Intro. He gave you a moral lesson that his surroundings made him feel that death would solve his problems cause life was hell on those streets.

"Damn right I like the Life I live, cause I went from Negative to Positive, and it's ALL GOOD" - JUICY

*READY TO INSPIRE: By 1995 Biggie was on top of the world and crowned The King of New York (Which is also his nickname). Touring the globe. Collaborating with rappers from the underground to commercial. To Pop Acts as big as Michael Jackson. “Ready To Die” dominated the charts, airways and the streets. Because of this the album created a new Blueprint for Hip Hop. Biggie made an LP that appealed to not just his boys at the bodega in Brooklyn but also that white kid in the suburbs. The album gave the streets what they wanted but it also gave the clubs something too. What LL did in the 80’s and early 90’s. Biggie took it to another level. His success lead to bringing out his crew Junior Mafia which lead to discovery of one of the greatest female rappers ever in Lil Kim. It also made Bad Boy records one of the most Successful and historic labels in rap History.

20 Years later “Ready To Die” is one of the most sampled rap albums of all time. “Juicy, Warning, Big Poppa and One More Chance” are still all staples on radio. Lyrics have been sampled from this album from rap, pop, rnb and even rock stars. The album as been on several of greatest of all time list including Time Magazine Top 100 albums ever. It even spanned the Blockbuster Diamond Selling Classic Masterpiece follow up “Life After Death”. Which literally acts as a sequel to “Ready To Die” which it begins at the end of “Suicidal Thoughts”. So on this Legendary Anniversary. What's your favorite song from the album and what's your opinion of it all these years later? 20 years ago Biggie may have been “Ready To Die”, but the music he made was Ready To Live. FOREVER.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ready_to_Die

The Making of ‘Ready To Die': Family Business - XXL

Last edited: