ogc163

Superstar

I was going to write a lengthy post explaining why “degrowth” — the idea that we need to halt economic growth in order to save the planet — is a very bad idea. But in the meantime, other people have written that post, or recorded that podcast, and done it well. These include Branko Milanovic, Kelsey Piper, and Ezra Klein. So instead I’ll write a shorter post trying to catalog and boil down the arguments against degrowth.

But first, let’s go over the standard argument, so we can see why these new arguments are necessary.

The standard argument against degrowth

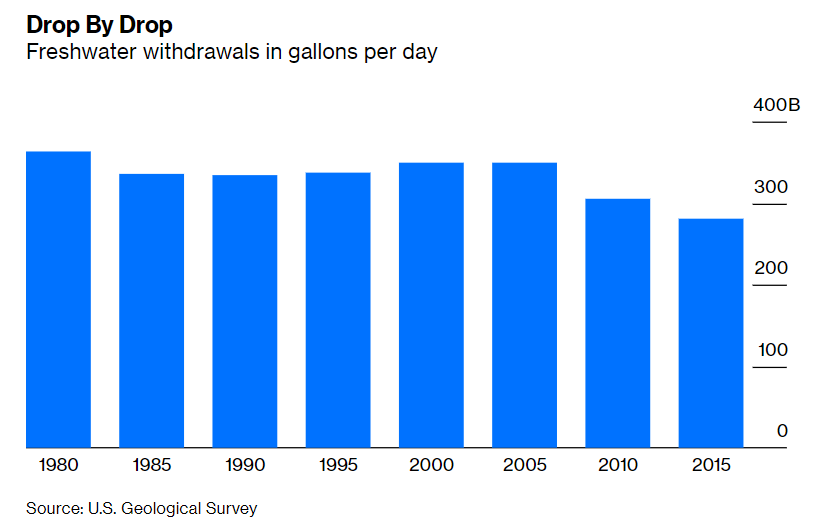

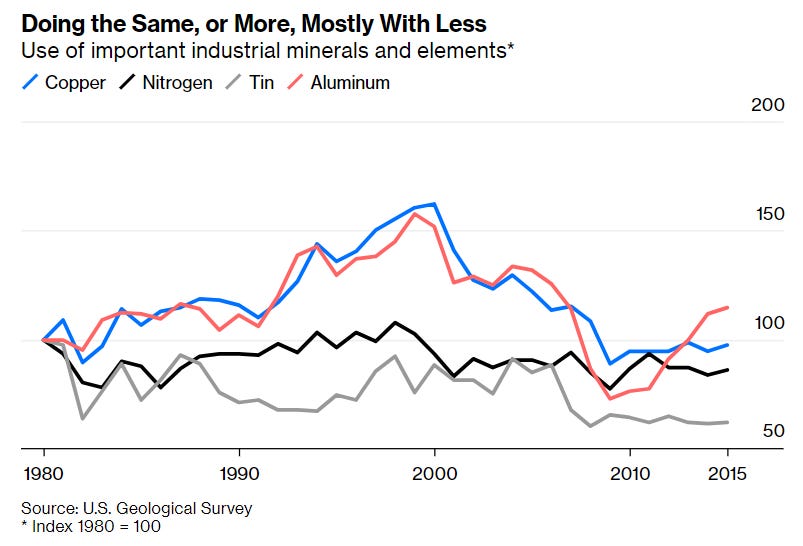

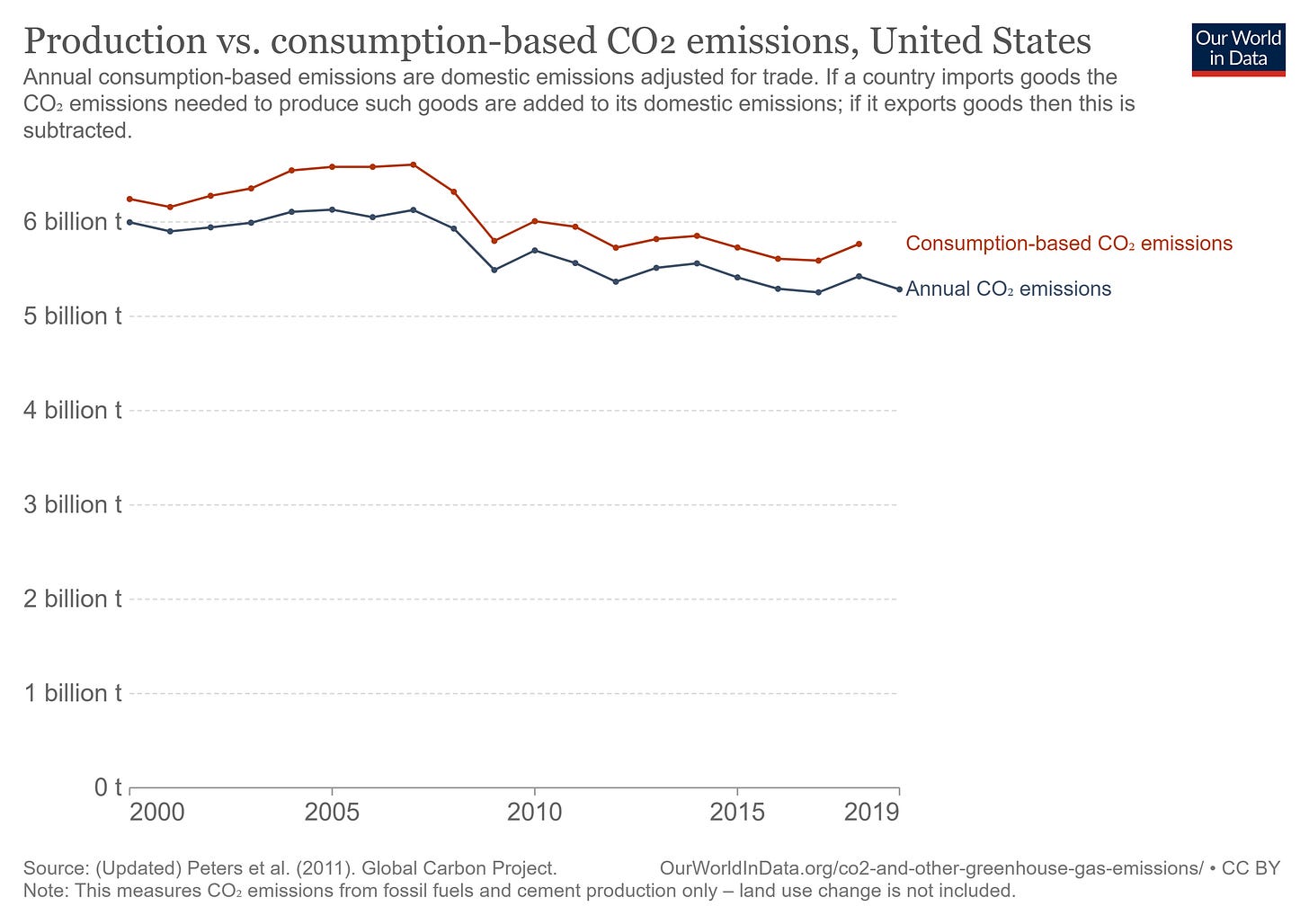

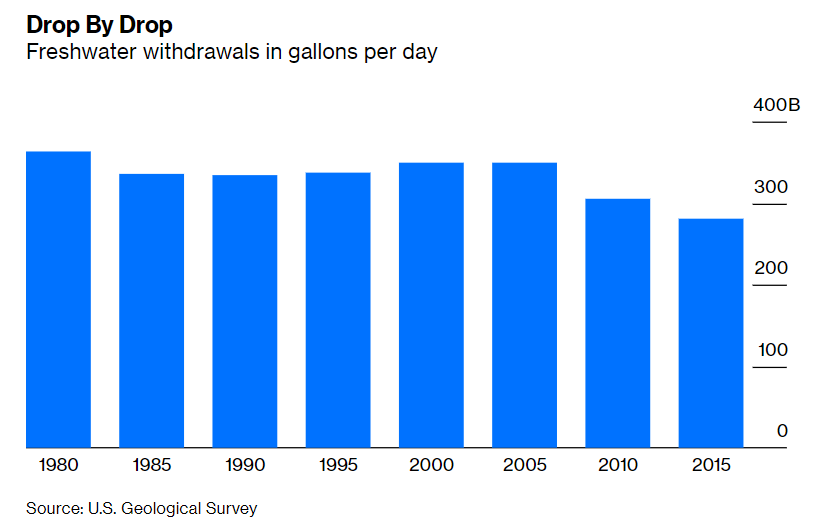

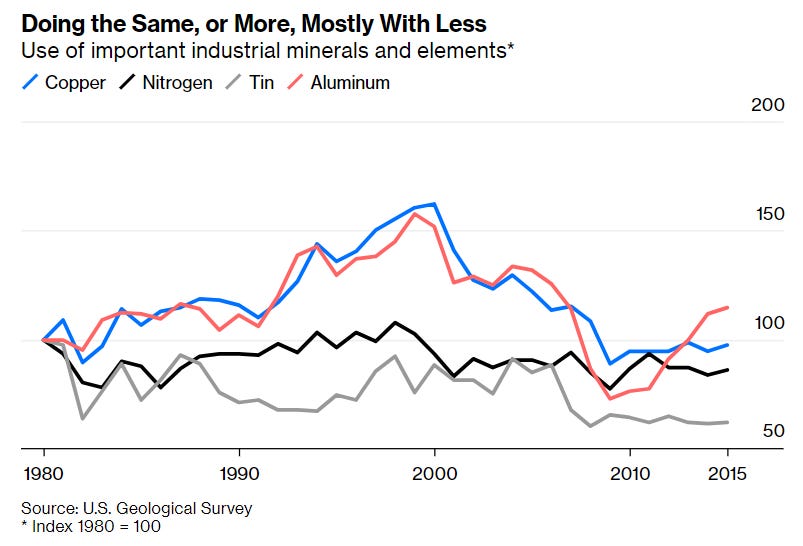

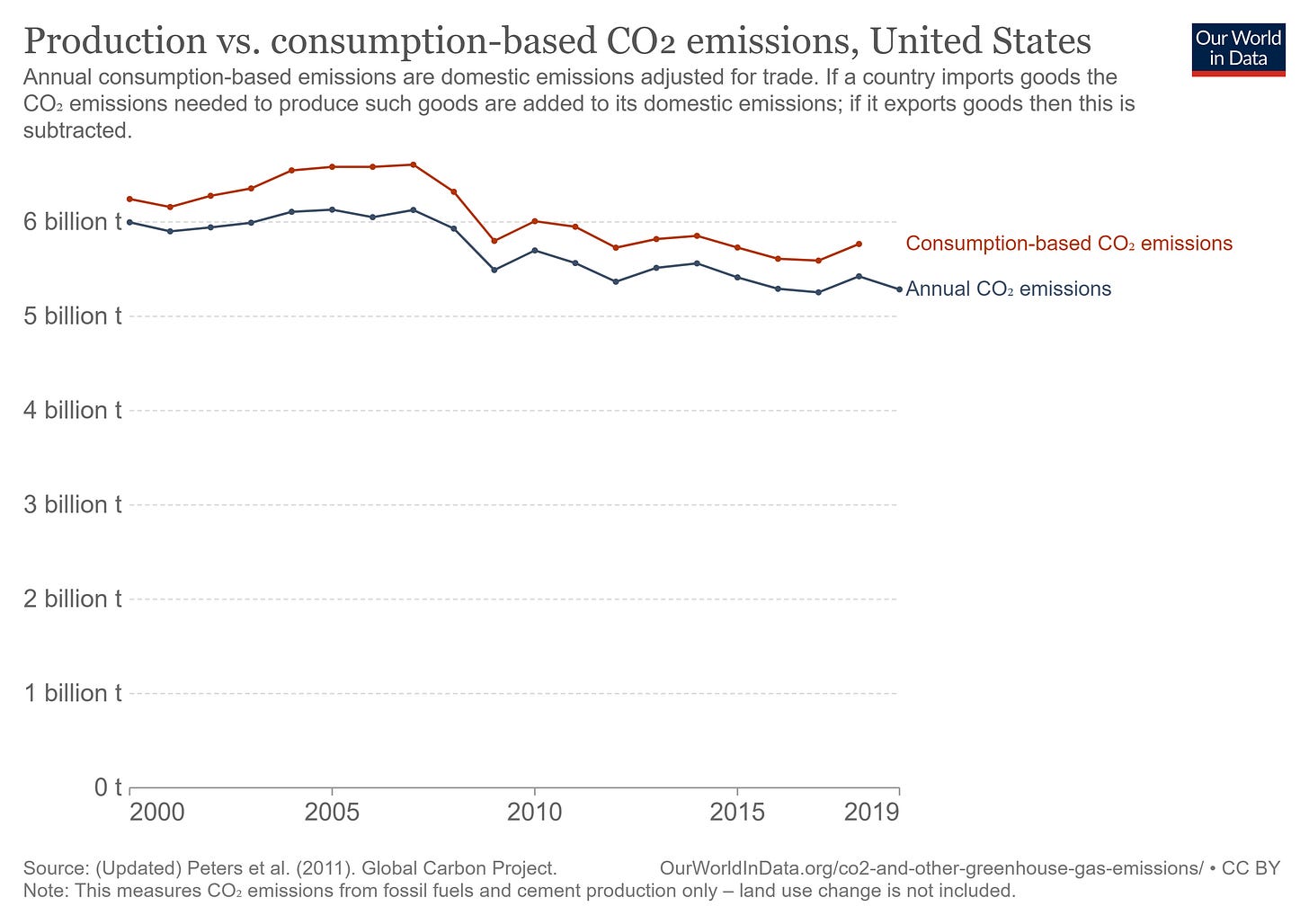

First, note that the typical argument against degrowth, which I laid out in a Bloomberg post a while back, is that we don’t need it; we can raise human living standards without exhausting the planet. This argument was capably put forward by Andy McAfee, in his excellent book More From Less, which you should buy and read. Essentially, the idea that economic growth requires growth in resource use is false; rich countries have started to grow while using less and less of the planet’s most important resources. For example, here is U.S. use of fresh water and various metals, as well as trade-adjusted carbon emissions:

So the idea here is that we don’t need degrowth; instead, we can keep raising everyone’s standard of living without exhausting the planet’s resources. Because growth doesn’t just mean using more and more stuff; instead, it can mean finding more efficient ways to use the stuff we have.

Degrowthers have two counters to this. Their first counter, typically, is to show a graph of resource use for the entire world, and show that it’s correlated with global growth. This is a weak response, for two reasons:

This argument isn’t as strong as it sounds — China and India and the rest will be able to take advantage of the efficiency-inducing technologies created by the developed countries, like solar power (indeed, they are already doing so). And they will be able to embrace “dematerialized” goods and services like social networks and video games (sorry, Xi Jinping) very early in their growth path. So these countries’ resource use trajectories won’t look quite like the U.S.’ or Europe’s.

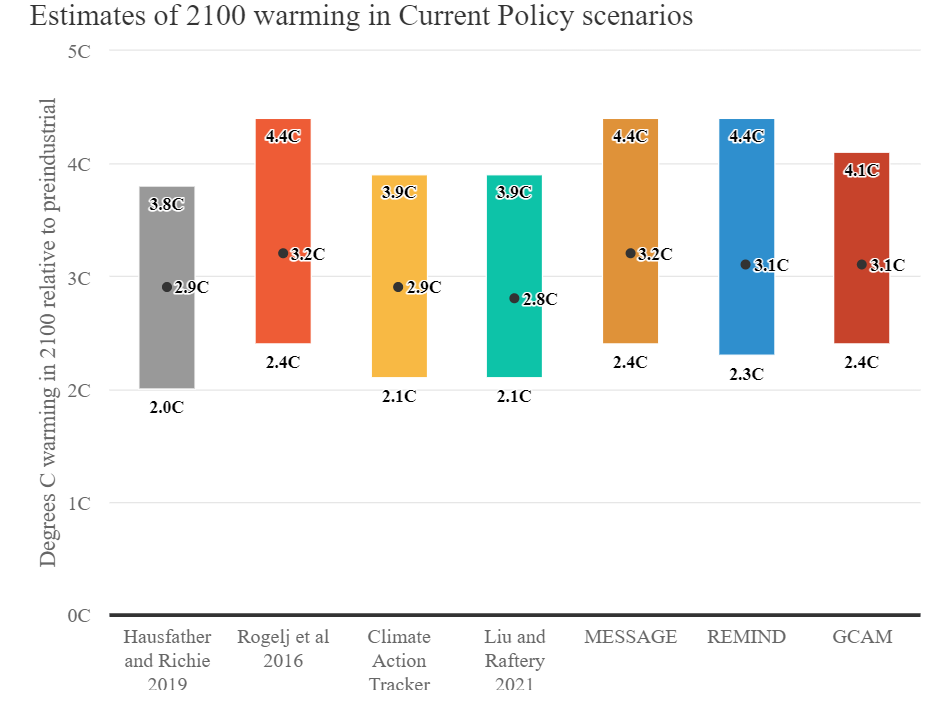

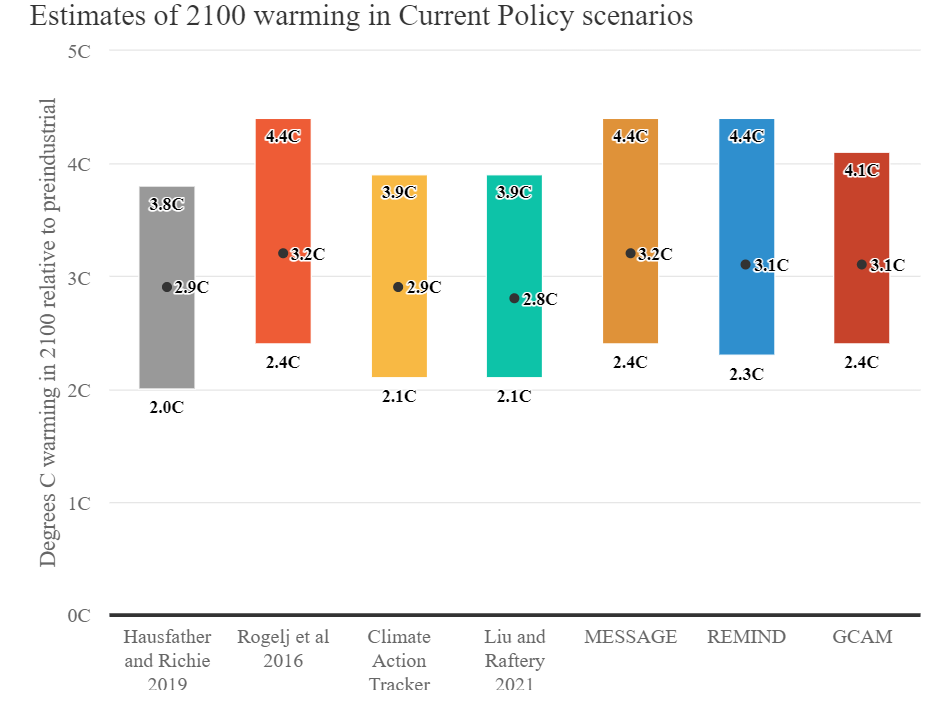

But this degrowther argument does contain a nugget of truth: Global resource use is currently on an unsustainable trajectory. Here, via Zeke Hausfather, are the current projections for global warming by century’s end, even with the advances in techologies like solar:

Any one of these scenarios represents utter global catastrophe.

So even if there is a sustainable growth path, we are not currently on it. About this, degrowthers are right; a gentle, natural transition to green growth is possible, but is an unaffordable luxury. But degrowthers’ prescription is the wrong one.

But first, let’s go over the standard argument, so we can see why these new arguments are necessary.

The standard argument against degrowth

First, note that the typical argument against degrowth, which I laid out in a Bloomberg post a while back, is that we don’t need it; we can raise human living standards without exhausting the planet. This argument was capably put forward by Andy McAfee, in his excellent book More From Less, which you should buy and read. Essentially, the idea that economic growth requires growth in resource use is false; rich countries have started to grow while using less and less of the planet’s most important resources. For example, here is U.S. use of fresh water and various metals, as well as trade-adjusted carbon emissions:

So the idea here is that we don’t need degrowth; instead, we can keep raising everyone’s standard of living without exhausting the planet’s resources. Because growth doesn’t just mean using more and more stuff; instead, it can mean finding more efficient ways to use the stuff we have.

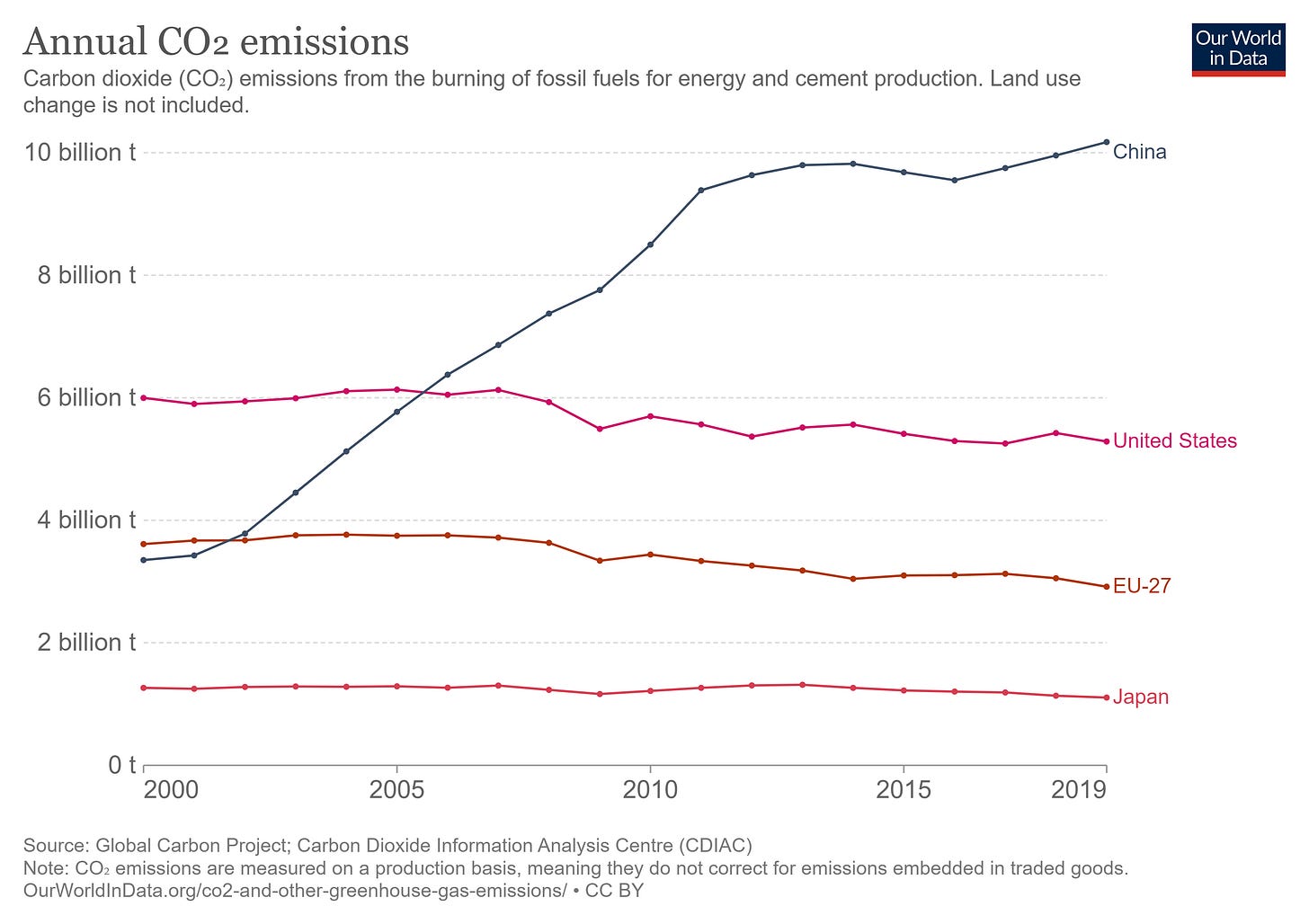

Degrowthers have two counters to this. Their first counter, typically, is to show a graph of resource use for the entire world, and show that it’s correlated with global growth. This is a weak response, for two reasons:

- Degrowthers have no idea how to combine various resources into an overall measure of resource use, so they typically go with gross weight. This is absurd, since some materials are recyclable and others are not — if you “use” a ton of copper you still have the copper, whereas if you “use” a ton of oil, your oil is gone. It’s also absurd because it doesn’t take into account the relative abundance of resources — if you figure out how to substitute 2 tons of sand for 1 ton of oil, you’re getting more efficient, since sand is much more plentiful than oil (and doesn’t pollute as much when you use it). A lot of growth is figuring out how to substitute plentiful resources for rare ones, and simply adding up gross tonnage ignores this.

- Past trends are no guarantee of future trends. Until the 70s, for instance, U.S. economic growth was closely correlated with both energy use and carbon emissions; after the 70s, this correlation broke down completely and the lines started moving in opposite directions. Degrowthers present historical curves as if these are laws of nature, but we know that they are not. The trend is your friend only til the bend at the end. And the fact that rich countries have hit an inflection point where economic growth no longer depends on growing resource use is a strong indicator that industrializing countries like China will also hit this point as well. (And no, falling use in rich countries is mostly not due to outsourcing, as the emissions graph above illustrates.)

This argument isn’t as strong as it sounds — China and India and the rest will be able to take advantage of the efficiency-inducing technologies created by the developed countries, like solar power (indeed, they are already doing so). And they will be able to embrace “dematerialized” goods and services like social networks and video games (sorry, Xi Jinping) very early in their growth path. So these countries’ resource use trajectories won’t look quite like the U.S.’ or Europe’s.

But this degrowther argument does contain a nugget of truth: Global resource use is currently on an unsustainable trajectory. Here, via Zeke Hausfather, are the current projections for global warming by century’s end, even with the advances in techologies like solar:

Any one of these scenarios represents utter global catastrophe.

So even if there is a sustainable growth path, we are not currently on it. About this, degrowthers are right; a gentle, natural transition to green growth is possible, but is an unaffordable luxury. But degrowthers’ prescription is the wrong one.

someones grandkids are fukked

someones grandkids are fukked