One Big, Unintended Consequence of the Failed Attempt to Ban the Abortion Pill

The more anti-abortion activists attacked mifepristone ... the more women flocked to use it.

One Thing the Failed Attempt to Ban the Abortion Pill Did

The more anti-abortion activists attacked mifepristone, the more women flocked to use it.

By Carrie N. BakerJune 18, 20245:45 AM

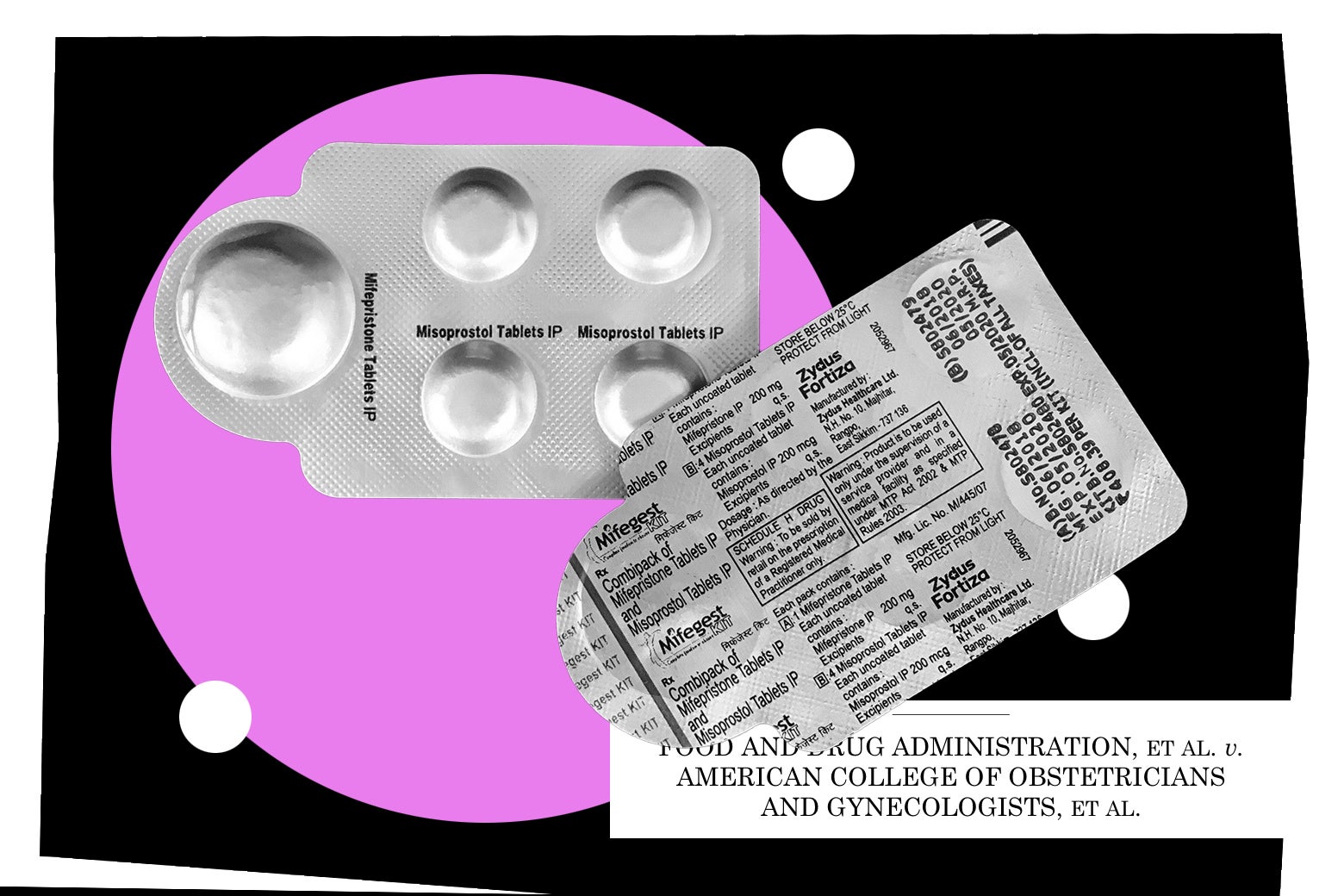

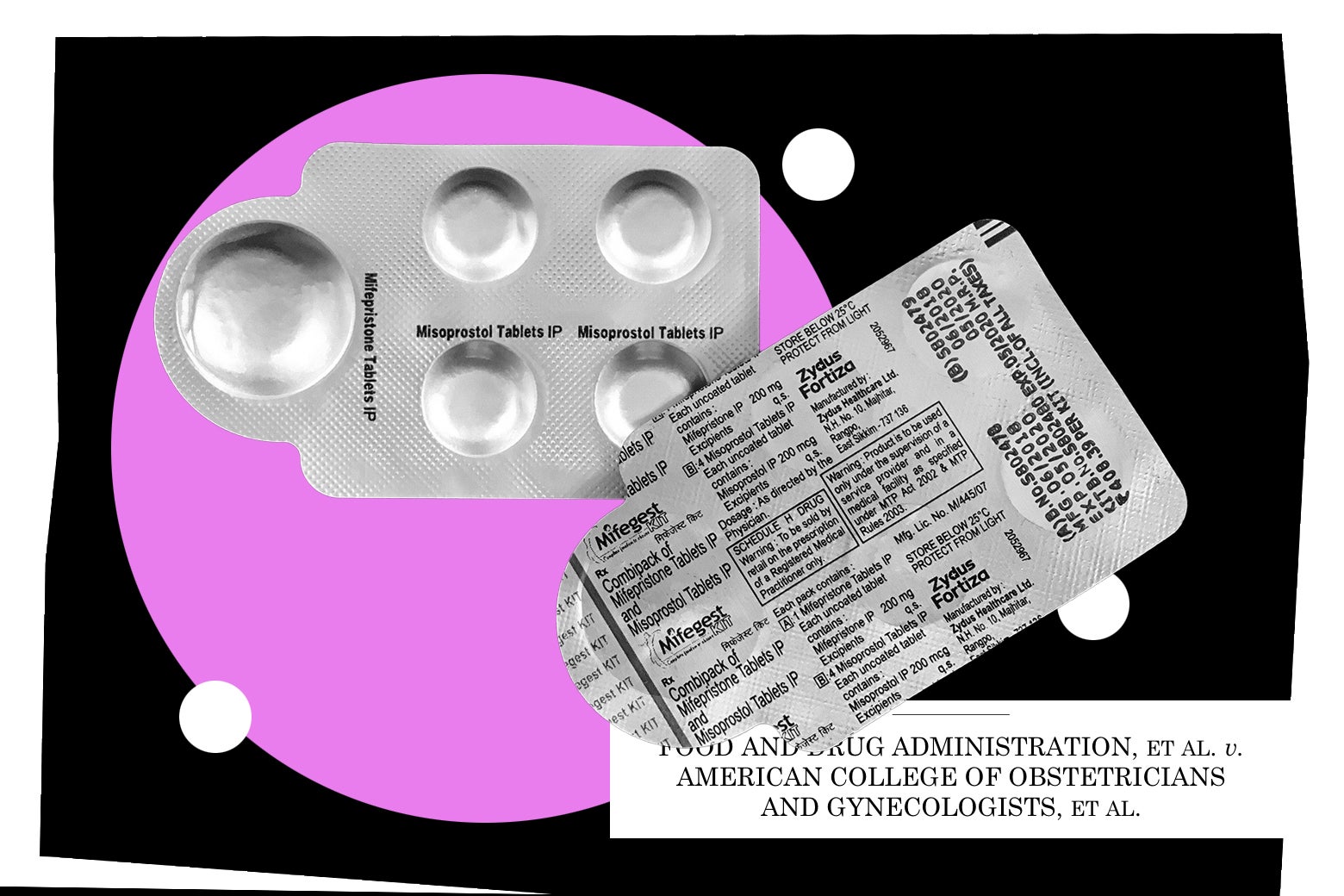

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Elisa Wells/Plan C/AFP via Getty Images and supremecourt.gov.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)

On Thursday, the Supreme Court dismissed a lawsuit, FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, that tried to restrict access to the abortion pill mifepristone based on false allegations that the medication was dangerous. The justices ruled that the plaintiffs—anti-abortion doctors and dentists who had never prescribed mifepristone and hadn’t treated women who had used the medication—did not have legal standing to bring the case. In a moment when the high court is understood to be highly politicized, the 9–0 ruling stood out as definitive, confirming the legality of the medication nationwide.

Although some evidence indicates that the case spread disinformation about the safety of abortion pills, the suit had unintended consequences. The demonization efforts have wound up being one giant publicity campaign for a medication that, for so many years, most women didn’t even know was an option.

“The SCOTUS case raised awareness of abortion pills and the pills-by-mail option,” said Elisa Wells, co-founder of Plan C, which maintains a website providing a comprehensive guide for obtaining abortion pills through telehealth, community networks, and online pill vendors in all 50 states. The case may have “also continued to spread the false perception that abortion pills are somehow dangerous or need extra regulation, which we know, from decades of research, is not true,” she said. But the ultimate effect might actually be quite positive for abortion access.

In 2023, while the mifepristone case garnered regular media coverage as it worked its way through the courts, the Plan C website received 2 million visits, doubling in the year after Roe v. Wade fell. On March 26, 2024, the day the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the mifepristone case, the website experienced a 50 percent increase in traffic, reported Plan C co-founder Amy Merrill. The same day, lawyers counseling people on the Repro Legal Helpline saw a 70 percent increase in inquiries about abortion pills.

A central legal question in the case was whether the Food and Drug Administration had had enough evidence when it approved mifepristone in 2000, then expanded access to the medication in 2016 and 2021. In widespread media coverage of the case, anti-abortion advocates and lawyers loudly proclaimed that abortion pills are dangerous, and abortion supporters argued that they are safe—even safer than Tylenol. Despite the comparatively equal declarations on each side, the suit brought substantial attention to the voluminous scientific research demonstrating the safety of abortion pills; the New York Times published a list of more than 100 such studies. Public scrutiny of abortion pill research in fact led academic publisher Sage to retract three published studies written by anti-abortion advocates—two of which had been cited in court filings in the mifepristone case—because of a “lack of scientific rigor.”

News articles repeatedly reported that over 5 million women have safely used mifepristone in the U.S. since the FDA’s approval of the medication and that across the world, many more millions have safely used mifepristone in the 96 countries that have approved it for abortion use.

Meanwhile, the country’s abortion pill use and telehealth with pills by mail climbed. A decade ago, less than a third of abortions in the United States were done with medications and telehealth abortion was not allowed by the FDA. Today, two-thirds of abortions are done with medications, and 1 in 5 are done through telehealth, with pills delivered by mail.

Telehealth abortion became widely available for the first time after the FDA permanently lifted the requirement, in December 2021, that medical providers dispense mifepristone directly to patients. This change spurred the proliferation of virtual abortion clinics, which used mail-order pharmacies to dispense the medication. It was in response to this increase in availability that anti-abortion activists filed the lawsuit to ban mifepristone in November 2022. Then, the following month, the FDA for the first time began allowing brick-and-mortar pharmacies to dispense abortion pills.

Despite the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade and 14 states banning abortion, the number of abortions in 2023 rose significantly over previous years. There were 1,037,190 clinician-supported abortions in the U.S. in 2023, the highest rate since 2012 and an 11 percent increase since 2020, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

The Guttmacher number is even likely to be an undercount—it does not include new telehealth services operating in six states with telehealth-provider shield laws that allow clinicians to mail abortion pills to women living in states that have banned abortion. Shield-state providers are now serving approximately 10,000 women a month, with demand steadily increasing.nanza for the very drug it sought to ban.