By George Monbiot, published in the Guardian 10th December 2013

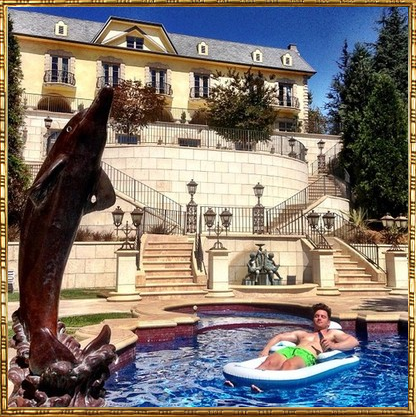

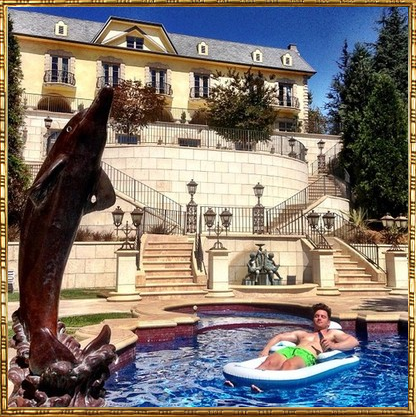

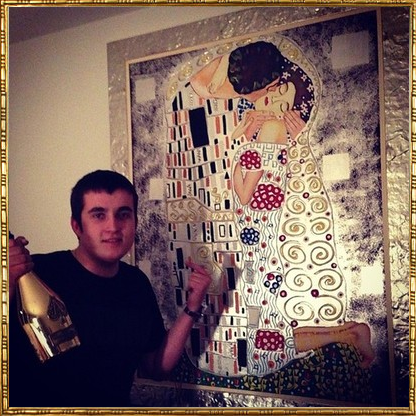

That they are crass, brash and trashy goes without saying. But there is something in the pictures posted on Rich Kids of Instagram (and highlighted by the Guardian last week(1)) that inspires more than the usual revulsion towards crude displays of opulence. There is a shadow in these photos – photos of a young man wearing all four of his Rolex watches(2), a youth posing in front of his helicopter(3), endless pictures of cars, yachts, shoes, mansions, swimming pools, spoilt white boys throwing gangster poses in private jets – of something worse; something that, after you have seen a few dozen, becomes disorienting, even distressing.

All photos taken from Rich Kids of Instagram

The pictures are, of course, intended to incite envy. They reek instead of desperation. The young men and women seem lost in their designer clothes, dwarfed and dehumanised by their possessions, as if ownership has gone into reverse. A girl’s head barely emerges from the haul of Chanel, Dior and Hermes shopping bags she has piled onto her vast bed(4). It’s captioned “shoppy shoppy” and “#goldrush”, but a photograph whose purpose is to illustrate plenty seems instead to depict a void. She’s alone with her bags and her image in the mirror, in a scene that seems saturated with despair.

Perhaps I am projecting my prejudices. But an impressive body of psychological research appears to support these feelings. It suggests that materialism, a trait that can afflict both rich and poor, which the researchers define as “a value system that is preoccupied with possessions and the social image they project”(5), is both socially destructive and self-destructive. It smashes the happiness and peace of mind of those who succumb to it. It’s associated with anxiety, depression and broken relationships.

There has long been a correlation observed between materialism, a lack of empathy and engagement with others, and unhappiness(6,7,8). But research conducted over the past few years appears to show causation.

For example, a series of studies published in June in the journal Motivation and Emotion showed that as people become more materialistic, their well-being (good relationships, autonomy, a sense of purpose and the rest) diminishes(9). As they become less materialistic, it rises.

In one study, the researchers tested a group of 18-year-olds, then re-tested them 12 years later. They were asked to rank the importance of different goals: jobs, money and status on one side, self-acceptance, fellow feeling and belonging on the other. They were then given a standard diagnostic test to identify mental health problems. At the ages of both 18 and 30, materialistic people were more susceptible to disorders. But if in that period they became less materialistic, their happiness improved.

That they are crass, brash and trashy goes without saying. But there is something in the pictures posted on Rich Kids of Instagram (and highlighted by the Guardian last week(1)) that inspires more than the usual revulsion towards crude displays of opulence. There is a shadow in these photos – photos of a young man wearing all four of his Rolex watches(2), a youth posing in front of his helicopter(3), endless pictures of cars, yachts, shoes, mansions, swimming pools, spoilt white boys throwing gangster poses in private jets – of something worse; something that, after you have seen a few dozen, becomes disorienting, even distressing.

All photos taken from Rich Kids of Instagram

The pictures are, of course, intended to incite envy. They reek instead of desperation. The young men and women seem lost in their designer clothes, dwarfed and dehumanised by their possessions, as if ownership has gone into reverse. A girl’s head barely emerges from the haul of Chanel, Dior and Hermes shopping bags she has piled onto her vast bed(4). It’s captioned “shoppy shoppy” and “#goldrush”, but a photograph whose purpose is to illustrate plenty seems instead to depict a void. She’s alone with her bags and her image in the mirror, in a scene that seems saturated with despair.

Perhaps I am projecting my prejudices. But an impressive body of psychological research appears to support these feelings. It suggests that materialism, a trait that can afflict both rich and poor, which the researchers define as “a value system that is preoccupied with possessions and the social image they project”(5), is both socially destructive and self-destructive. It smashes the happiness and peace of mind of those who succumb to it. It’s associated with anxiety, depression and broken relationships.

There has long been a correlation observed between materialism, a lack of empathy and engagement with others, and unhappiness(6,7,8). But research conducted over the past few years appears to show causation.

For example, a series of studies published in June in the journal Motivation and Emotion showed that as people become more materialistic, their well-being (good relationships, autonomy, a sense of purpose and the rest) diminishes(9). As they become less materialistic, it rises.

In one study, the researchers tested a group of 18-year-olds, then re-tested them 12 years later. They were asked to rank the importance of different goals: jobs, money and status on one side, self-acceptance, fellow feeling and belonging on the other. They were then given a standard diagnostic test to identify mental health problems. At the ages of both 18 and 30, materialistic people were more susceptible to disorders. But if in that period they became less materialistic, their happiness improved.

relatively speaking, of course

relatively speaking, of course