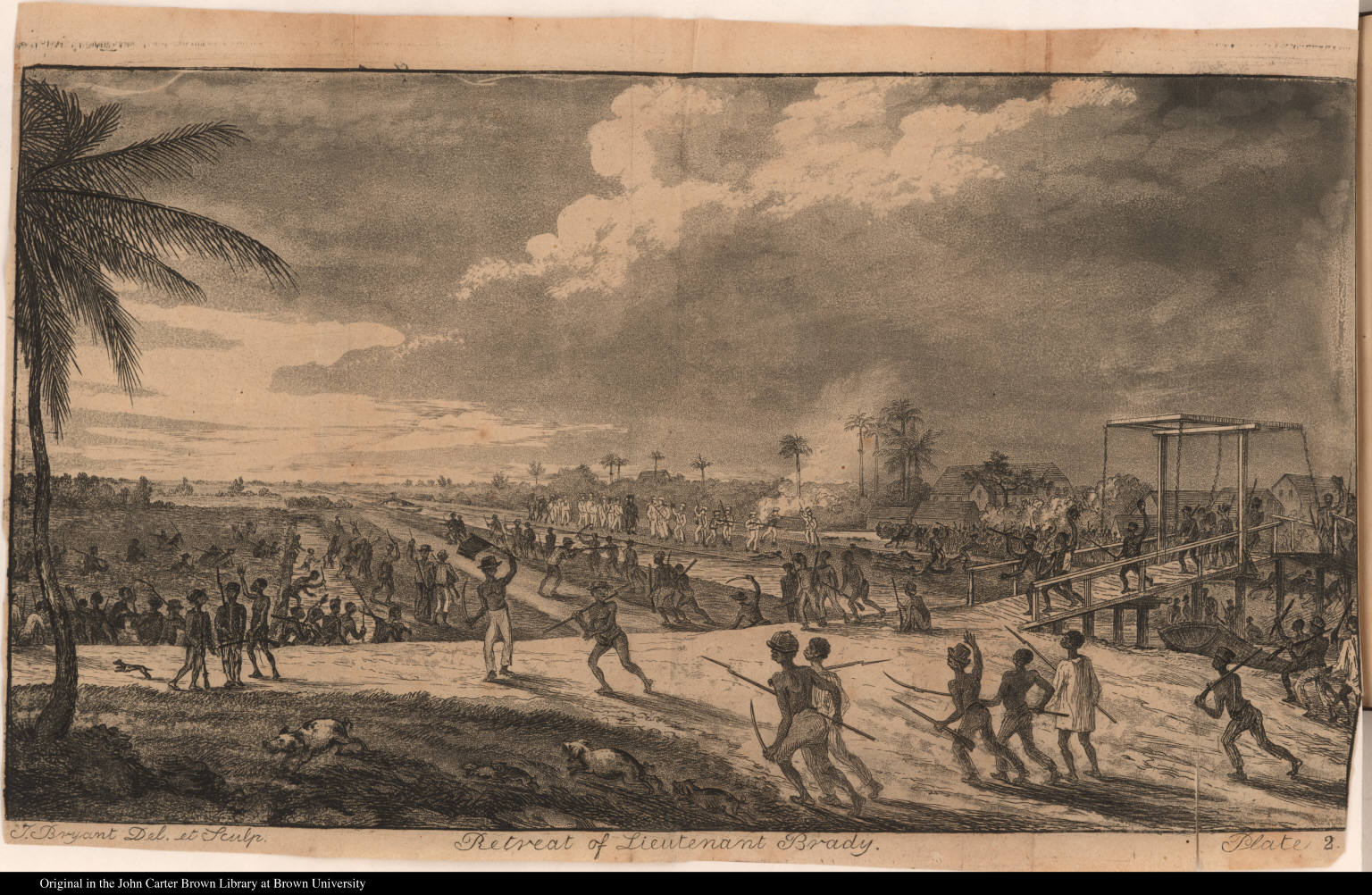

Depiction of battle at "Bachelor's Adventure", one of the major confrontations during the rebellion

The revolt

Slaves with the highest status such as coopers, and some other who were members of Smith's congregation, were implicated in leading the rebellion

[4] against the harsh conditions and maltreatment, demanding what they believed to be their right.

Quamina and his son

Jack Gladstone, both slaves on "Success" plantation, led their peers to revolt.

[30] Quamina, a member of Smith's church,

[3] had been one of five chosen to become deacons by the congregation soon after Smith's arrival.

[31] In the British House of Commons in May 1823,

Thomas Fowell Buxton introduced a resolution condemning the state of slavery as "repugnant to the principles of the British constitution and of the Christian religion", and called for its gradual abolition "throughout the British colonies".

[8] In fact, the subject of these rumours were Orders in Council (to colonial administrations) drawn up by

George Canning under pressure from abolitionists to ameliorate the conditions of slaves following a Commons debate. Its principal provisions were to restrict slaves' daily working hours to nine and to prohibit flogging for female slaves.

[4]

Whilst the Governor or Berbice immediately made a proclamation upon receiving his orders from London, and instructed local parson John Wray to explain the provisions to his congregation,

[4] John Murray, his counterpart in Demerara, had received the Order from London on 7 July 1823, and these measures proved controversial as they were discussed in the Court of Policy on 21 July and again on 6 August.

[4][8] They were passed as being inevitable, but the administration made no formal declaration as to its passing.

[4] The lack of formal declaration led to rumours that masters had received instructions to set the slaves free but were refusing to do so.

[4] In the weeks prior to the revolt, he sought confirmation of the veracity of the rumours from other slaves, particularly those who worked for those in a position to know: he thus obtained information from Susanna, housekeeper/mistress of John Hamilton of "Le Resouvenir"; from Daniel, the Governor's servant; Joe Simpson from "Le Reduit" and others. Specifically, Simpson had written a letter which said that their freedom was imminent but which warned them to be patient.

[32] Jack wrote a letter (signing his father's name) to the members of the chapel informing them of the "new law".

[33]

Those on "Le Resouvenir", where Smith's chapel was situated, also rebelled.

[3] Quamina, who was well respected by slaves and freedmen alike,

[34] initially tried to stop the slave revolt,

[35] and urged instead for peaceful strike; he made the fellow slaves promise not to use violence.

[33][36] As an artisan cooper who did not work under a driver, Jack enjoyed considerable freedom to roam about.

[22] He was able to organise the rebellion through his formal and informal networks. Close conspirators who were church 'teachers' included Seaton (at "Success"), William (at "Chateau Margo"), David (at "Bonne Intention"), Jack (at "Dochfour"), Luke (at "Friendship"), Joseph (at "Bachelor's Adventure"), Sandy (at "Non Pareil"). Together, they finalised planning in the afternoon of Sunday

17 August for thousands of slaves to raise up against their masters the next morning.

[37]

Joe of "Le Reduit" had informed his master at approximately 6 am that morning of a coordinated uprising planned the night before at Bethel chapel which would take place that same day. Captain Simpson, the owner, immediately rode to see the Governor, but stopped to alert several estates on the way into town. The governor assembled the cavalry, which Simpson was a part of.

[38] Although the rebellion leaders had hoped for mass action by all slaves, the actual unrest involved about 13,000 slaves over some 37 estates located on the east coast,

between Georgetown and Mahaica.

[30] Slaves entered estates, ransacked the houses for weapons and ammunition, tied up the whites, or put some into stocks.

[3][30] The very low number of white deaths is cited as proof that the uprising was largely free from violence from the slaves.

[4] Accounts from witnesses indicate that the rebels exercised restraint, with only a very small number of white men were killed.

[39][4] Some slaves took revenge on their masters or overseers by putting them in stocks, like they themselves had been before. Slaves went in large groups, from plantation to plantation, seizing weapons and ammunition and locking up the whites, promising to release them in three days. However, according to Bryant, not all slaves were compliant with the rebels; some were loyal to their masters and held off against the rebels.

[39]

The Governor immediately declared

martial law.

[3] The 21st Fusiliers and the

1st West India Regiment, aided by a volunteer battalion, were dispatched to combat the rebels, who were armed mainly with cutlasses and bayonets on poles, and a small number of stands of rifles captured from plantations.

[40] By the late afternoon on 20 August, the situation had been brought under control. Most of the slaves had been rounded up, although some of the rebels were shot whilst attempting to flee. On 22 August 1823, Lieutenant Governor Murray issued an account of the battles. He reported major confrontations on Tuesday morning at the Reed estate, "Dochfour", where ten to fifteen of the 800 rebels were killed; a skirmish at "Good Hope" felled "five or six" rebels. On Wednesday morning, six were killed at 'Beehive' plantation, forty rebels died at Elizabeth Hall. At a battle which took place at "Bachelor's Adventure", "a number considerably above 1500" were involved.

[40]

The Lieutenant-Colonel having in vain attempted to convince these deluded people of their error, and every attempt to induce them to lay down their arms having failed, he made his dispositions, charged the two bodies simultaneously, and dispersed them with the loss of 100 to 150. On our side, we only had one rifleman slightly wounded.

—Extract of communiqué from His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief, 22 August 1823

[40]

After the slaves' defeat at "Bachelor's Adventure", Jack fled into the woods. A "handsome reward"

[41] of one thousand guilder was offered for his capture.

[42] The Governor also proclaimed a "FULL and FREE PARDON to all slaves who surrendered within 48 hours, provided that they shall not have been ringleaders (or guilty of Aggravated Excesses)".

[43] Jack remained at large until he and his wife were captured by Capt. McTurk at "Chateau Margo", after a three-hour standoff on 6 September