ogc163

Superstar

The Coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc on New York City’s economy and has revealed, and exacerbated, the existing socioeconomic disparities that afflict communities of color in the city. As Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration looks to ensure a fair recovery that focuses on racial equity, a new report shows that there are deep disparities in income and employment for Black New Yorkers that will require a concerted, long-term effort to address.

The report, released Monday by the Center for an Urban Future (CUF), a nonprofit think tank, found that Black New Yorkers hold a staggeringly low number of jobs in high-paying industries and face “strikingly large” income disparities compared to white workers across the economy. The report analyzed pre-tax wage and salary income data across 140 industries from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey’s five-year sample.

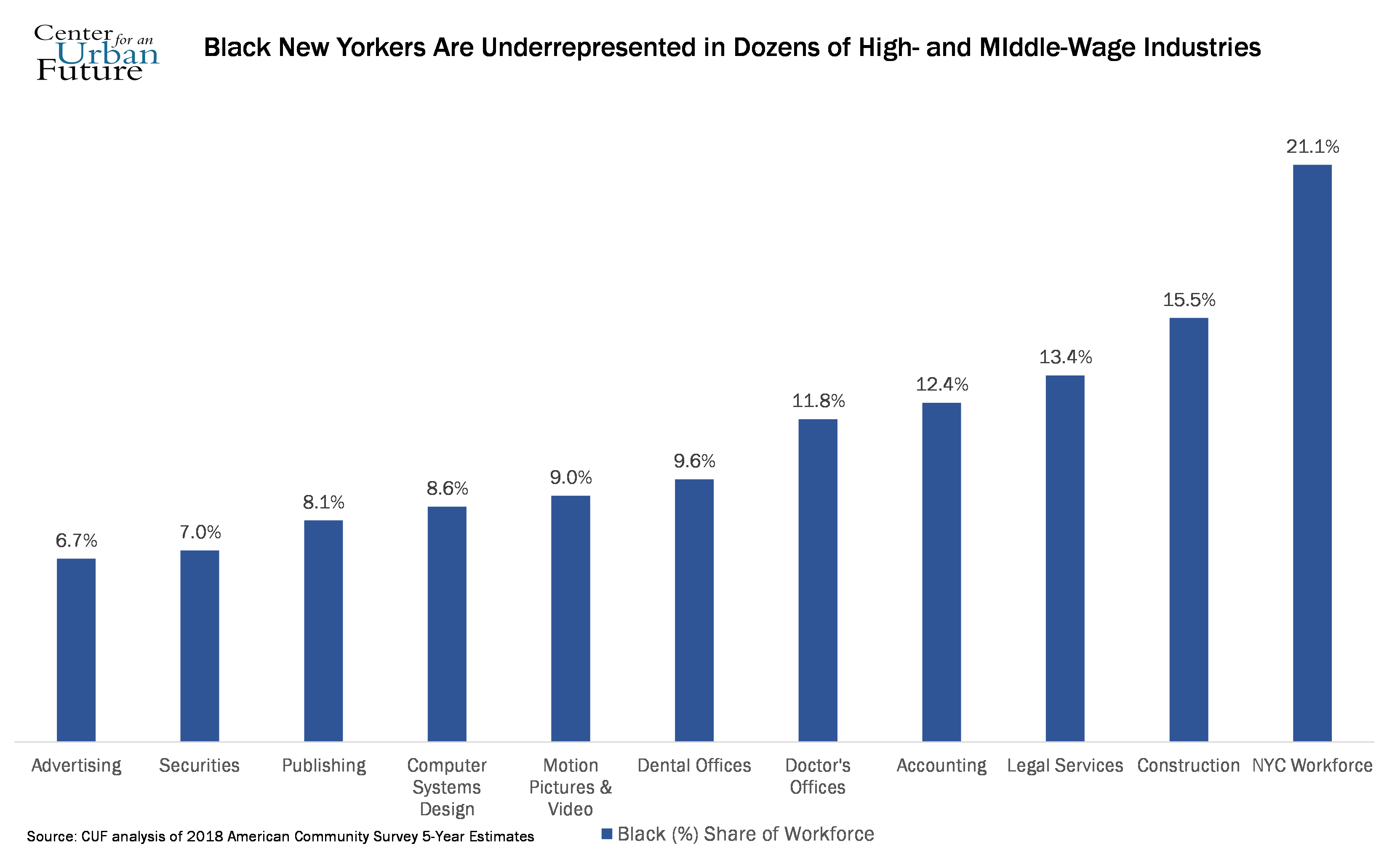

Though Black New Yorkers make up 22% of the city’s population and 21.1% of the workforce, the report found that they are underrepresented in dozens of high- and middle-wage industries, accounting for less than 15% of the workforce in sectors such as technology, finance and insurance, creative industries, manufacturing, business services, and medical and dental offices. In some industries, such as scientific research and development, Black workers make up as little as 6% of the workforce.

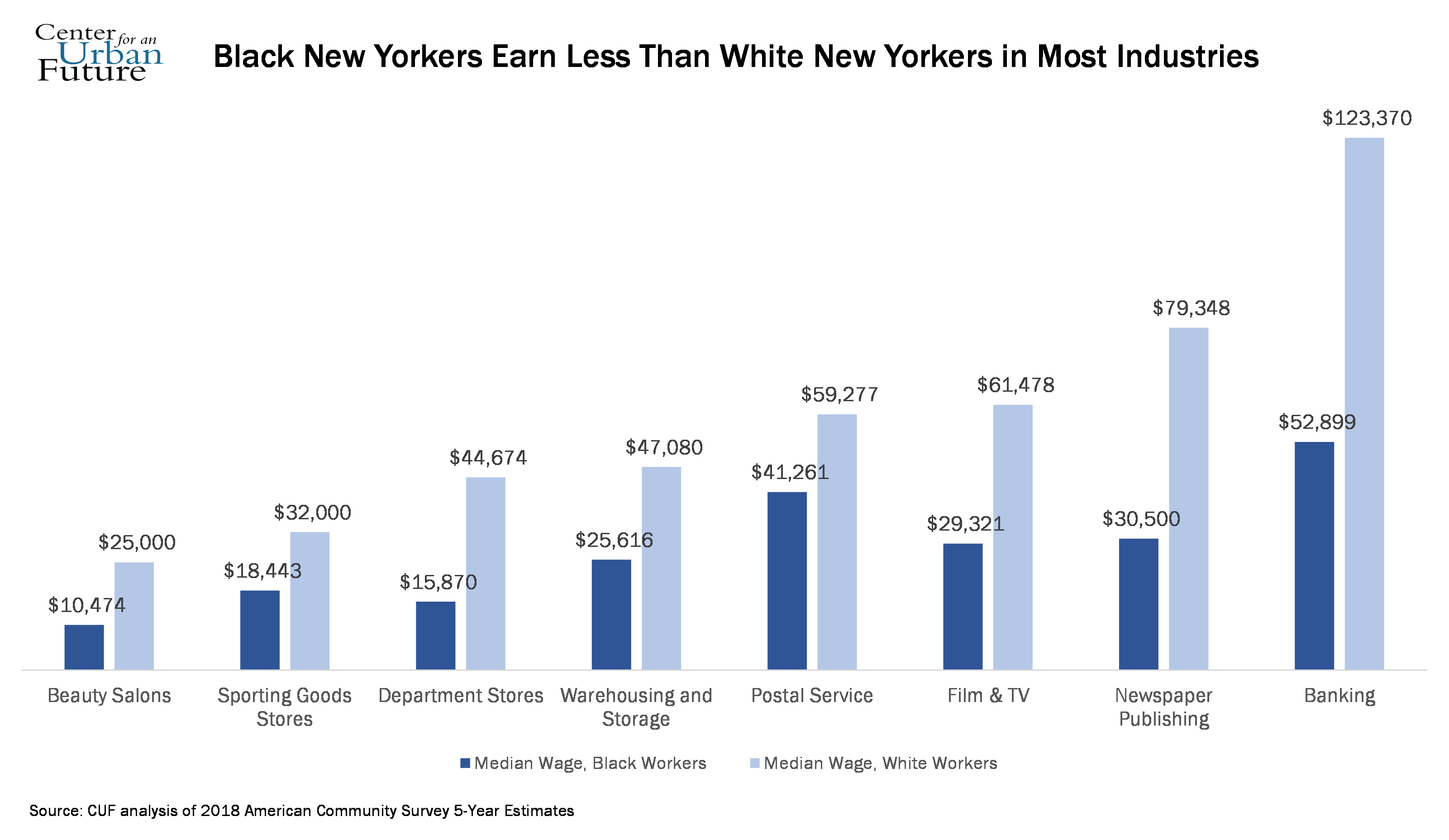

Wage gaps for Black New Yorkers, compared with white workers, were apparent across the board. Black workers made more than white workers in only 12 of the 140 industries that the study examined. In 92 of those industries, the gap in median annual income was more than $10,000. For instance, Black workers in department stores had a median annual income of $15,870, compared to $44,674 for their white counterparts. The biggest difference was in the banking industry, where the median annual wage for Black workers was $52,899, compared to $123,370 for white workers.

“Often, industries that typically produce middle-wage jobs for white New Yorkers pay near-poverty wages to Black New Yorkers,” the report stated. Wage gaps were similarly present in the warehousing and storage industry, sporting goods stores, beauty salons, newspaper publishing, the film & tv sector, banking, to name a few industries.

“No matter the scale of the challenge, closing these gaps should be among the city’s highest policy priorities and will require a dedicated and long-term response,” the report states. “For the city’s economy not only to recover from the current crisis, but to reemerge more equitable and inclusive, policymakers will need to take strong steps to help more Black New Yorkers gain footholds – and advance – in a diverse range of well-paying and accessible fields.”

The report recommends that the city expand programs to help Black New Yorkers advance in postsecondary education, invest in training for tech careers and apprenticeship programs, and enlist top industry executives that can improve hiring practices from within an industry, among other measures.

The city has taken some steps along that path. Recognizing the racially disparate impact of the pandemic, Mayor de Blasio in April created a Fair Recovery Taskforce and a Taskforce on Racial Inclusion and Equity, co-chaired by First Lady Chirlane McCray, to ensure that the city addresses the longstanding disparities in communities of color. The taskforce has recommended several initiatives over the last few months to provide services and resources to hard-hit neighborhoods and populations. Just last week, the mayor announced a program to assist Black-owned businesses and promote Black entrepreneurship. “The challenge of disparity, the challenge of income inequality, it has come up so sharply in the course of these last few months, but it's something we've been grappling with for a long time, and this needs to be a moment when we resolve to make more fundamental changes,” de Blasio said at the announcement. “The coronavirus itself and the economic crisis that's come with, it has hit so hard in communities of color. It's hit immigrants so hard. It's hit small businesses so hard. We have so much work to do to create something better and fairer, and that's what we're going to do.”

Though the CUF report did not study the reasons behind wage and employment disparities in depth, it does surmise that disparities are partially connected to education. It notes that most jobs in high-paying industries go to people with four-year college or graduate degrees – 68.6% of white New Yorkers in the workforce have a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education while only 30.7% of Black New Yorkers can say the same.

The report notes that there are several other factors that also play a part, including “hiring practices that disadvantage Black candidates, unequal access to peer networks and mentorship, the harmful effects of poverty, and the impact of systemic racism.”

There are also industries, including several that have been considered essential workers during the pandemic, where Black New Yorkers are overrepresented. For instance, Black workers accounted for 58% of nursing care facility employees, 49% of workers in community food, housing, and emergency services, and 48% of investigation and security services workers. Industries where Black employees were generally paid on par or more than white workers included child day care, convenience stores, nail salons, barber shops, taxi and limousine services, and construction, among others.

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

New Report Highlights Sharp Income and Employment Disparities for Black New Yorkers

The report, released Monday by the Center for an Urban Future (CUF), a nonprofit think tank, found that Black New Yorkers hold a staggeringly low number of jobs in high-paying industries and face “strikingly large” income disparities compared to white workers across the economy. The report analyzed pre-tax wage and salary income data across 140 industries from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey’s five-year sample.

Though Black New Yorkers make up 22% of the city’s population and 21.1% of the workforce, the report found that they are underrepresented in dozens of high- and middle-wage industries, accounting for less than 15% of the workforce in sectors such as technology, finance and insurance, creative industries, manufacturing, business services, and medical and dental offices. In some industries, such as scientific research and development, Black workers make up as little as 6% of the workforce.

Wage gaps for Black New Yorkers, compared with white workers, were apparent across the board. Black workers made more than white workers in only 12 of the 140 industries that the study examined. In 92 of those industries, the gap in median annual income was more than $10,000. For instance, Black workers in department stores had a median annual income of $15,870, compared to $44,674 for their white counterparts. The biggest difference was in the banking industry, where the median annual wage for Black workers was $52,899, compared to $123,370 for white workers.

“Often, industries that typically produce middle-wage jobs for white New Yorkers pay near-poverty wages to Black New Yorkers,” the report stated. Wage gaps were similarly present in the warehousing and storage industry, sporting goods stores, beauty salons, newspaper publishing, the film & tv sector, banking, to name a few industries.

“No matter the scale of the challenge, closing these gaps should be among the city’s highest policy priorities and will require a dedicated and long-term response,” the report states. “For the city’s economy not only to recover from the current crisis, but to reemerge more equitable and inclusive, policymakers will need to take strong steps to help more Black New Yorkers gain footholds – and advance – in a diverse range of well-paying and accessible fields.”

The report recommends that the city expand programs to help Black New Yorkers advance in postsecondary education, invest in training for tech careers and apprenticeship programs, and enlist top industry executives that can improve hiring practices from within an industry, among other measures.

The city has taken some steps along that path. Recognizing the racially disparate impact of the pandemic, Mayor de Blasio in April created a Fair Recovery Taskforce and a Taskforce on Racial Inclusion and Equity, co-chaired by First Lady Chirlane McCray, to ensure that the city addresses the longstanding disparities in communities of color. The taskforce has recommended several initiatives over the last few months to provide services and resources to hard-hit neighborhoods and populations. Just last week, the mayor announced a program to assist Black-owned businesses and promote Black entrepreneurship. “The challenge of disparity, the challenge of income inequality, it has come up so sharply in the course of these last few months, but it's something we've been grappling with for a long time, and this needs to be a moment when we resolve to make more fundamental changes,” de Blasio said at the announcement. “The coronavirus itself and the economic crisis that's come with, it has hit so hard in communities of color. It's hit immigrants so hard. It's hit small businesses so hard. We have so much work to do to create something better and fairer, and that's what we're going to do.”

Though the CUF report did not study the reasons behind wage and employment disparities in depth, it does surmise that disparities are partially connected to education. It notes that most jobs in high-paying industries go to people with four-year college or graduate degrees – 68.6% of white New Yorkers in the workforce have a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education while only 30.7% of Black New Yorkers can say the same.

The report notes that there are several other factors that also play a part, including “hiring practices that disadvantage Black candidates, unequal access to peer networks and mentorship, the harmful effects of poverty, and the impact of systemic racism.”

There are also industries, including several that have been considered essential workers during the pandemic, where Black New Yorkers are overrepresented. For instance, Black workers accounted for 58% of nursing care facility employees, 49% of workers in community food, housing, and emergency services, and 48% of investigation and security services workers. Industries where Black employees were generally paid on par or more than white workers included child day care, convenience stores, nail salons, barber shops, taxi and limousine services, and construction, among others.

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

New Report Highlights Sharp Income and Employment Disparities for Black New Yorkers

?

?

So so wrong.

So so wrong.