Doobie Doo

Veteran

Why Doesn’t Boston Give New Edition Their Due?

Forget New Kids on the Block—New Edition is the greatest pop group Boston has ever produced. So 40 years after they rocketed out of Roxbury, why don’t they get their due in their own hometown?

by G. VALENTINO BALL· 8/21/2018, 6:45 a.m.

A snapshot of the original Roxbury group in the early ’80s. / Photo via Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

For many Bostonians, hearing the crack of the bat and enjoying a hot dog at Fenway is the ultimate sign of summer. For others, it’s navigating Friday-evening traffic for a trip down the Cape, or sprawling on the Esplanade and listening to the Boston Pops unleash their incendiary finale on the Fourth of July. In Dorchester, Mattapan, and Roxbury—the neighborhoods where I grew up—it’s the hum of mopeds and minibikes weaving through traffic like Grand Prix racers, the colorful costumes and thumping rhythms of the Caribbean Carnival, and the sounds of backyard barbecues, complete with a DJ set, that mark the change of seasons. And to me, one of the essential sounds of summer has always been New Edition—made up of five local guys from Roxbury. It’s almost a ’hood requirement that the summer soundtrack include at least a few of the group’s classic hits.

Call it nostalgia, maybe. Or a nod to my music-nerd roots. Whatever it is, I have a healthy dash of hometown pride for the band, which was cranking out chart-toppers before they could shave. In the years since New Edition rode their sweet harmonies and slick dance moves to fame—and sometimes infamy—there’s always been a part of Boston that remembers These are our guys. But lately, I’ve started to wonder whether the people who live here now—and even some who’ve lived here as long as I have—know the talent and the impact they truly had.

When I was growing up, New Edition was a kind of fantasy story come true. The first incarnation of the group came together in 1978 in Roxbury’s Orchard Park Projects, just a few miles from my home in Dorchester. In the late ’70s, the 350-unit cement public housing complex was one of the toughest spots in the city—an honor it would lose only when it was torn down in 1998. There, Bobby Brown, Michael Bivins, and Ricky Bell—later joined by Ralph Tresvant and Ronnie DeVoe—honed their act during daily rehearsals. They played school auditoriums and talent shows at Uphams Corner’s Strand Theatre—I’d see the posters for their performances on my walk to school. When the group won a record deal from producer and local celebrity Maurice Starr, who wrote hits including “Candy Girl” and “Popcorn Love” for them, they became superstars but remained Boston to the core.

Now, 40 years after their careers began, I’d argue that the members of New Edition had as much influence on pop music as any act in Boston. They were the band that Starr then modeled his next group after, shaping Boston heartthrobs New Kids on the Block in the image of New Edition (though their pipes and their moves weren’t quite as good). Once the Roxbury kids grew older, they led R & B into the hip-hop era and helped define new jack swing, which mixed R & B, jazz, electronica, and hip-hop. They consistently topped the charts. And they did it all with some of the crispiest choreography this side of Motown.

Lately, there’s been a bloom of new appreciation for New Edition across the country. Last year, the lauded BET miniseries The New Edition Storyrehashed the band’s breakups, makeups, and on-stage fisticuffs. The cable network is following it up with The Bobby Brown Story, coming in September. A few years ago, Vibe recounted the reasons why New Edition should be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. But while they remain national icons, they seem to consistently get low billing in their hometown. Bostonians love to fawn over the city’s illustrious rock ’n’ roll history, but how many know that New Edition changed the face of pop music, launched a thousand boy bands, and might just be Boston’s most important pop export of all time? It’s about time these hometown heroes got their due.

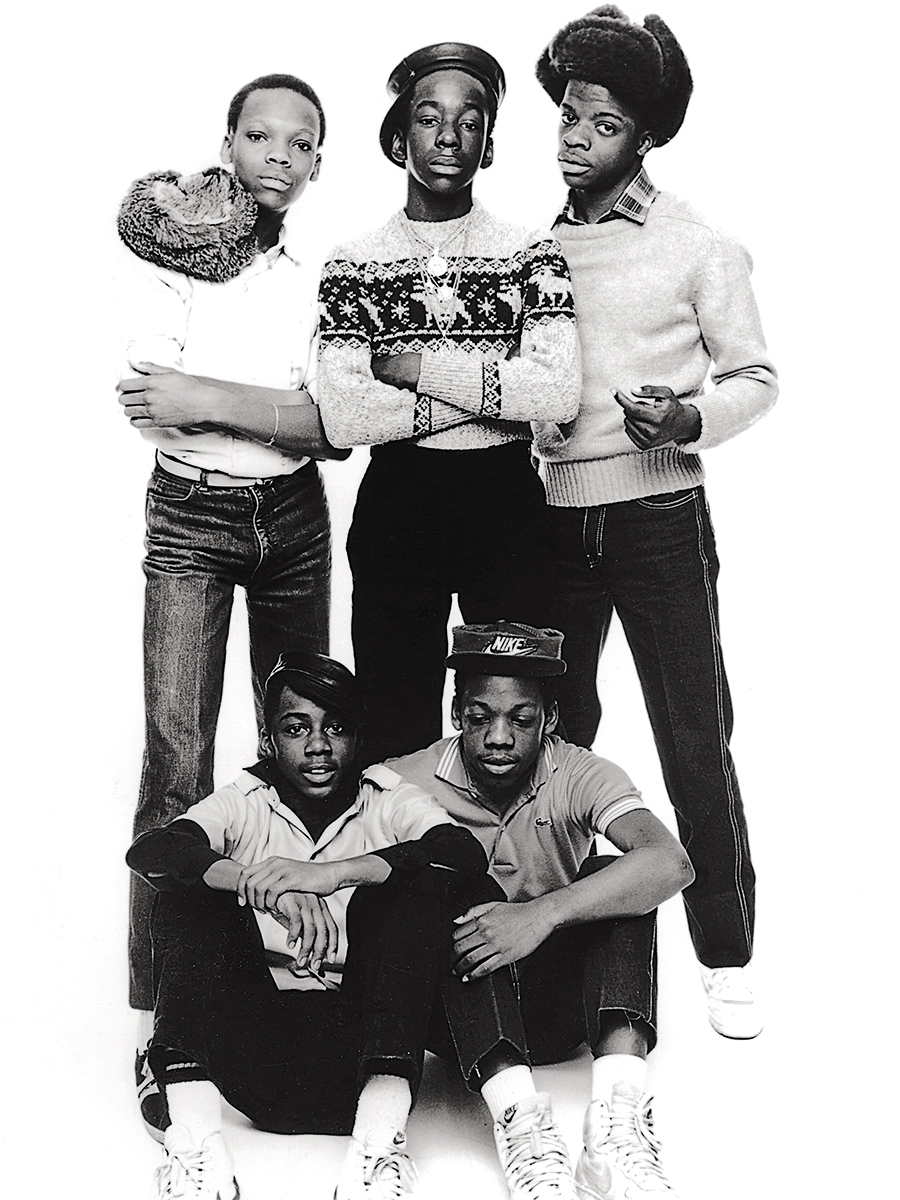

A young New Edition, of the “Candy Girl” era: Ronnie DeVoe, Bobby Brown, and Ricky Bell (top), with Ralph Tresvant and Michael Bivins (front). / Photo by Echoes/Redferns

Roxbury today is very different from when New Edition started coming together. There were no boutique coffee spots, such as Dudley Café, to grab a latte; the elevated tracks of the Orange Line still cast a shadow on the streets of Dudley Square; and you could hear the wail of trains turning into the station from just about anywhere in the projects. Mayor Kevin White’s city-sponsored concert series, Summerthing, was still around, and a fresh pair of Adidas Superstars—known as Shelltoes—would make any kid the envy of the neighborhood.

Brown, Bell, and Bivins were about 10 years old when the idea of forming New Edition came to them. They added two other friends from the neighborhood, who didn’t stick with the group, and ultimately brought in Ralph Tresvant from Orchard Park to be the lead singer. They also worked with Brooke Payne, a local choreographer, who set up daily practices to hone their singing and their steps. Before long, the group became a neighborhood draw. “They were doing all the talent shows,” says Dana “Daneja” Bradley, a longtime fixture in Boston’s music scene, first as a DJ and then as a promoter. “My cousin LaBaron Jones and Ralph were best friends” and they’d hang out at Ralph’s house and wait for the practice sessions to end. “When they were doing the New Edition stuff, as a kid it was like, ‘When are you gonna be finished so we can go play?’” After all, what they were doing was cool, but it wasn’t out of the ordinary. “Everybody had their little group growing up—you were either in a rap group or singing group or dance group,” Bradley says. Even so, the New Edition singers stood out. “They were going super-hard-body at it, always rehearsing,” he says. “But you never imagine it getting big—to where they got to.”

That success story, full of glitz and fame, started on November 15, 1981. When New Edition took the stage at the Strand Theatre to sing a Jackson 5 medley for Hollywood Talent Night, their destiny was on the line. The prize was a recording contract, and even though they finished second in the competition, Starr liked what he saw and signed them. He added a fifth member to round out the roster, Payne’s nephew Ronnie DeVoe, from Dorchester, and handed the band a song he had been working on: “Candy Girl.” A little over a year later, it was a smash hit. “Candy Girl” spent weeks on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart and took the top spot on the Hot R & B Singles and U.K. charts. And the guys singing it were Boston all the way down to the Adidas Shelltoes they rocked as they descended the stairs of the Northampton Orange Line station in the music video. They looked like kids from around the way because that’s exactly what they were—they dressed like everyone I went to school with.

Almost overnight, these hardworking performers from the neighborhood became honest-to-God celebrities. Their faces were plastered all over the covers of the music mags—Fresh! and Word Up!—that I’d take the train up to Harvard Square to buy at Out of Town News with my allowance money. The elementary school auditoriums of their talent-show days gave way to sold-out arenas and stadiums. Geoff “Geespin” Gamere, the onetime DJ for the local hip-hop outfit Microphone Thunder, who now develops acts for United Talent Agency’s music division, watched New Edition mania explode in Boston. “There used to be a concert series downtown called Concerts on the Common,” Gamere says. “I remember seeing [New Edition] and there were just a bunch of screaming girls. That was the go-to show at the time, too. It wouldn’t just be the city. Kids from the ’burbs would come down. It was almost like an early festival vibe.” When New Edition played the Kiss 108 concert at the old Boston Garden in 1985, just after their second album, he says his whole school went just to see them.

That same year, internal drama in the group rose to a boil. Egos clashed, and they started fighting off-stage, and occasionally mid-show. Bobby Brown, who had chafed at the band’s squeaky-clean appearance, had become such a problem that the other members voted to kick him out. He went solo the next year, cultivating a bad-boy image that later included a tumultuous marriage to Whitney Houston. Johnny Gill, the only non-Bostonian in the group, joined after Brown’s departure, bringing a smooth, mature voice to the then-teenage band. Other members spun off into their own acts, too. There was the trio Bell Biv DeVoe, as well as solo projects from Gill and Tresvant. But beyond the drama and the breakups and reunions, they kept making hits until, at some point, they faded from pop culture. So what’s happened to their legacy since then?

When New Edition showed up at oliver wendell Holmes Elementary in Dorchester for a surprise concert one day in the early ’90s, Sharra Gaston had no idea they’d grown up less than 15 minutes from where she did. A second grader at the time, Gaston had been listening to “Candy Girl” practically since she was born, and to her, New Edition was the epitome of stardom. “As a child in the pre–social media era, the only way you really saw your favorite artists was on TV or in person,” says Gaston, who later went on to work in the music business. “That was the day I realized that they were from Boston, like me. And that put them in an entirely different sphere from other artists—success suddenly felt tangible. I was a child, but I had the thought that I could go and pursue my dreams of obtaining a certain amount of fame and come back to the place that I live and show people that they could make it out.”

It’s almost shocking that—less than a decade after they were the talk of Roxbury—someone could grow up in the next neighborhood over and not know the members of New Edition had walked the same streets. Arguably, it reflects the priorities of the tastemakers who tell us what’s important here—historically, Boston has had a rather, ah, pale complexion. It’s not necessarily intentional. People talk about what they see around them, and there are a lot of rock acts that started in Boston. Aerosmith, sure, but also the Cars, the Modern Lovers, the Pixies, the Lemonheads, Mission of Burma, and Boston, obviously. “Boston’s built on a marsh,” quipped a Globeretrospective on the city’s pop history, “but it sure feels founded on rock.” But the weight of our rock ’n’ roll history can steamroll the other things that were going on here.

To some, the emphasis on rock is another example of Boston’s long struggle to recognize its black history. “Boston always overlooks, or wholesale erases, the accomplishments of its black residents,” says Dart Adams, a Boston-born music journalist and historian. “It took Donna Summer’s death for the city to finally embrace her and claim her. Had BET never done The New Edition Story or the upcoming Bobby Brown Story, Boston would probably still be overlooking them even 35 years after they broke out with ‘Candy Girl.’”

Still, the story with New Edition might be a little more complicated. One reason they don’t receive the same hometown love as many of their peers is that rocky relationships within the band haven’t always made it easy to be a fan. Plans for a full-scale reunion project and tour with all six members, along with the cast of the BET series, were announced and later scrapped—leaving Bell, Bivins, DeVoe, and Brown to hit the road as the newly christened RBRM. But unlike some hometown bands that reliably return to show the city some love, there isn’t a Boston stop planned on the RBRM tour—you’ll have to travel all the way to Foxwoods to see them.

Geespin also points out that the band has been off the scene for a while. “Both Aerosmith and New Kids continue to have strong careers, so they deserve the accolades they get,” he says. “Maybe if [New Edition] were able to continually tour and deliver music over the past 20 years, we would have a different convo.” Despite this, he says, New Edition’s fan base is still strong. “I think what the miniseries showed is that New Edition gets the love and accolades from the people whose lives they affected with the music.” The question is, will the rest of Boston get on the bandwagon?