88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

More Research Shows Voter ID Laws Hurt Minorities

Black and Latino voters are “increasingly losing their place in the democratic process.”

AP/Ric Feld

Ever since photo voter ID laws began popping up in states during the late 2000s, there’s been a partisan war over whether they’re good for democracy. Voter ID’s most loyal followers are Republicans, who believe they are needed to combat voter-impersonation fraud. Democrats are voter ID’s most loyal enemies, concerned that the laws suppress voter participation, especially for people of color. There have been a variety of studies that aim to hash this out, most of them producing mixed results that either side could exploit.

But a trio of political scientists at the University of California San Diego say they’re getting closer to the truth about the impact of voter ID laws: “For Latinos, Blacks, and multi-racial Americans there are strong signs that strict photo identification laws decrease turnout.”

This was a key finding in a new working paper from UCSD researchers Zoltan Hajnal, Nazita Lajevardi, and Lindsay Nielson, who compared voter turnout rates between states with voter ID laws and those without. According to their analysis, no other demographic has as much difficulty as black and brown voters under these laws. “The results are clear,” the researchers state plainly in the paper.

Their study shows how wide the racial gaps are in voter turnout between states with and without voter ID requirements. Looking at general election outcomes from 2008 to 2012, the researchers found that Latino turnout was 10.3 points lower in states where photo ID is necessary to vote than for Latinos in states where it is not. For primary elections, they found that states with strict photo voter ID laws depressed Latino turnout by 6.3 points compared to Latinos in non-voter ID states, and depressed African-American turnout by 1.6 points.

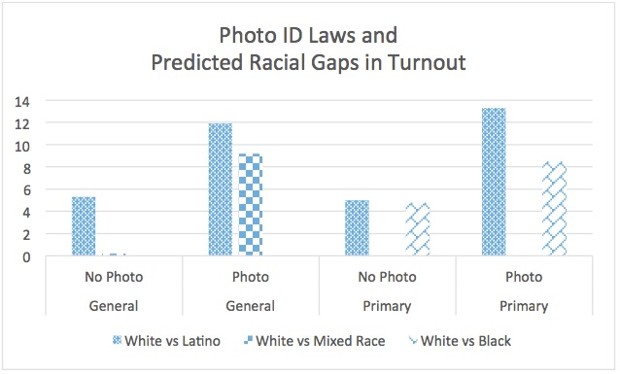

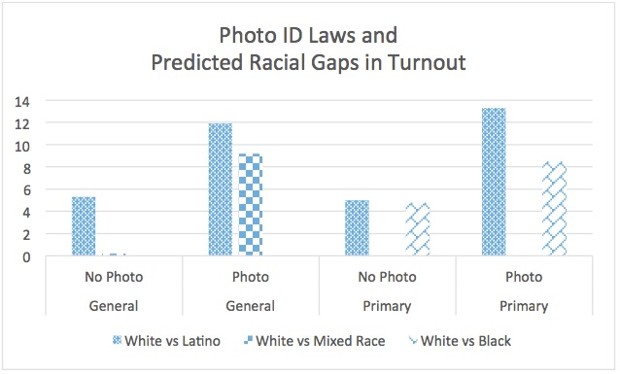

When looking at the voter turnout rates between whites and non-whites under voter ID laws, the guidelines continued to have a dampening effect. White voters already generally cast ballots at higher ratesthan Latino and black voters in most states, but that imbalance is intensified by voter ID requirements. In states where ID is not needed to vote, the gap between white and Latino turnout rates is just 5.3 percent in general elections. But that number jumps to 11.9 percent in states that do require ID. There’s a 4.8 percent gap between black and white turnout in non-voter ID states compared with a 8.5 percent gap between black and white voters in voter ID states. The chart below illustrates the mismatches:

(Zoltan Hajnal, Nazita Lajevardi, and Lindsay Nielson)

Meanwhile, white voters are “largely unaffected” by the laws, write the researchers, but black and brown voters have been “falling further and further behind and increasingly losing their place in the democratic process.”

From the report:

For the courts and for American democracy the core question should be—are these laws fair? Do they limit the access and participation of the nation’s most disadvantaged? Are these laws racially discriminatory? The findings presented here indicate that these laws do, in fact, have real consequences for the makeup of the voting population. Where they are enacted, racial and ethnic minorities are less apt to vote. The voices of Latinos, Blacks, and multi-racial Americans all become more muted and the relatively influence of white Americans grows. An already significant racial skew in American democracy becomes all the more pronounced.

As conclusive as the study sounds, the researchers admit that it does not settle the matter for good: “Our analysis cannot definitively show a causal connection between voter ID laws and turnout,” reads the study. But their results bolster a large body of work that has found similar effects, including reports from theU.S. Government Accountability Office, the University of Florida voting rights expert Daniel “ElectionSmith” Smith, and even fivethirtyeight.com’s Nate Silver.

It’s an important time to get closure on the question of whether these laws are harmful or not. This year’s presidential elections do not have a standout candidate like Barack Obama, who inspired African Americans to vote in record numbers, soany problems with turnout will be more apparent. And the next two primary elections in this year’s race are in states—New Hampshire and South Carolina—with voter ID laws. South Carolina went to court over its law in 2012, after the U.S. Justice Department rejected it, and was ultimately forced by a federal judge to lighten its restrictions under the Voting Rights Act.

However, the section of the act responsible for taming that law has beendeactivated, thanks to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision. North Carolina used that occasion to create its own voter ID law, which includes other statutes that could make it even more difficult for minorities to vote. Civil rights groups aren now in a legal fight with North Carolina over the new law and hope to have it removed before the state’s primary.

Voter ID isn’t the only controversial feature facing the electorate this year. As the UCSD political scientists point out in their study, there are also cuts to early voting periods, eliminating same-day voter registration, and confusion aroundproving one’s citizenship when registering to vote. There are unsettled questions about how all of these changes will affect voter participation, especially in combination.

“The more we answer these kinds of questions,” reads the UCSD study, “the more we will be able to offer accurate assessments of the fairness of American democracy and the more we will be able to recommend a clear path forward.”

'The Results are Clear': Voter ID Laws Hurt Black and Latino Voters

Black and Latino voters are “increasingly losing their place in the democratic process.”

- BRENTIN MOCK

- @brentinmock

- 4:27 PM ET

- Comments

AP/Ric Feld

Ever since photo voter ID laws began popping up in states during the late 2000s, there’s been a partisan war over whether they’re good for democracy. Voter ID’s most loyal followers are Republicans, who believe they are needed to combat voter-impersonation fraud. Democrats are voter ID’s most loyal enemies, concerned that the laws suppress voter participation, especially for people of color. There have been a variety of studies that aim to hash this out, most of them producing mixed results that either side could exploit.

But a trio of political scientists at the University of California San Diego say they’re getting closer to the truth about the impact of voter ID laws: “For Latinos, Blacks, and multi-racial Americans there are strong signs that strict photo identification laws decrease turnout.”

This was a key finding in a new working paper from UCSD researchers Zoltan Hajnal, Nazita Lajevardi, and Lindsay Nielson, who compared voter turnout rates between states with voter ID laws and those without. According to their analysis, no other demographic has as much difficulty as black and brown voters under these laws. “The results are clear,” the researchers state plainly in the paper.

Their study shows how wide the racial gaps are in voter turnout between states with and without voter ID requirements. Looking at general election outcomes from 2008 to 2012, the researchers found that Latino turnout was 10.3 points lower in states where photo ID is necessary to vote than for Latinos in states where it is not. For primary elections, they found that states with strict photo voter ID laws depressed Latino turnout by 6.3 points compared to Latinos in non-voter ID states, and depressed African-American turnout by 1.6 points.

When looking at the voter turnout rates between whites and non-whites under voter ID laws, the guidelines continued to have a dampening effect. White voters already generally cast ballots at higher ratesthan Latino and black voters in most states, but that imbalance is intensified by voter ID requirements. In states where ID is not needed to vote, the gap between white and Latino turnout rates is just 5.3 percent in general elections. But that number jumps to 11.9 percent in states that do require ID. There’s a 4.8 percent gap between black and white turnout in non-voter ID states compared with a 8.5 percent gap between black and white voters in voter ID states. The chart below illustrates the mismatches:

(Zoltan Hajnal, Nazita Lajevardi, and Lindsay Nielson)

Meanwhile, white voters are “largely unaffected” by the laws, write the researchers, but black and brown voters have been “falling further and further behind and increasingly losing their place in the democratic process.”

From the report:

For the courts and for American democracy the core question should be—are these laws fair? Do they limit the access and participation of the nation’s most disadvantaged? Are these laws racially discriminatory? The findings presented here indicate that these laws do, in fact, have real consequences for the makeup of the voting population. Where they are enacted, racial and ethnic minorities are less apt to vote. The voices of Latinos, Blacks, and multi-racial Americans all become more muted and the relatively influence of white Americans grows. An already significant racial skew in American democracy becomes all the more pronounced.

As conclusive as the study sounds, the researchers admit that it does not settle the matter for good: “Our analysis cannot definitively show a causal connection between voter ID laws and turnout,” reads the study. But their results bolster a large body of work that has found similar effects, including reports from theU.S. Government Accountability Office, the University of Florida voting rights expert Daniel “ElectionSmith” Smith, and even fivethirtyeight.com’s Nate Silver.

It’s an important time to get closure on the question of whether these laws are harmful or not. This year’s presidential elections do not have a standout candidate like Barack Obama, who inspired African Americans to vote in record numbers, soany problems with turnout will be more apparent. And the next two primary elections in this year’s race are in states—New Hampshire and South Carolina—with voter ID laws. South Carolina went to court over its law in 2012, after the U.S. Justice Department rejected it, and was ultimately forced by a federal judge to lighten its restrictions under the Voting Rights Act.

However, the section of the act responsible for taming that law has beendeactivated, thanks to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision. North Carolina used that occasion to create its own voter ID law, which includes other statutes that could make it even more difficult for minorities to vote. Civil rights groups aren now in a legal fight with North Carolina over the new law and hope to have it removed before the state’s primary.

Voter ID isn’t the only controversial feature facing the electorate this year. As the UCSD political scientists point out in their study, there are also cuts to early voting periods, eliminating same-day voter registration, and confusion aroundproving one’s citizenship when registering to vote. There are unsettled questions about how all of these changes will affect voter participation, especially in combination.

“The more we answer these kinds of questions,” reads the UCSD study, “the more we will be able to offer accurate assessments of the fairness of American democracy and the more we will be able to recommend a clear path forward.”

'The Results are Clear': Voter ID Laws Hurt Black and Latino Voters