OfTheCross

Veteran

What's the adage?..."you're the middle of your 5 closest friends..."

It makes sense that having richer friends will make you step up.

But the new study is the first to show that living in a place that fosters these connections causes better economic outcomes, using a significantly larger data set than other studies, covering 21 billion Facebook friendships.

The researchers limited the data, which did not include names, to active Facebook users. They estimated users’ incomes based on their ZIP codes, college, phone model, age and other characteristics.

For each low-income Facebook user, the researchers determined where the person was currently living, and how many high-income friends they had. That gave them a measure of how economically connected each neighborhood was. Then they compared the new data with earlier research that used tax records to measure how much a particular neighborhood raised low-income children’s economic prospects.

The researchers were also able to link almost 20 million users to both their high school and to their parents on Facebook. Using those ties, they repeated their analysis, this time on high school connections between children of rich and poor parents, to measure the impact of relationships made early in life. They did a similar analysis for teenage Instagram users. And they built on an earlier analysis of siblings who moved at different ages to show that it was the place that made a difference, versus something about the families who moved to those places.

Each analysis had the same result: The more connections between the rich and poor, the better the neighborhood was at lifting children from poverty. After accounting for these connections, other characteristics that the researchers analyzed — including the neighborhood’s racial composition, poverty level and school quality — mattered less for upward mobility, or not at all.

“It’s a big deal because I think what we lack in America today, and what’s been dropping catastrophically over the last 50 years, is what I call ‘bridging social capital’ — informal ties that lead us to people who are unlike us,” said Robert Putnam, the political scientist at Harvard who wrote “Bowling Alone” and “Our Kids,” about the decline of social capital in the United States. “And it’s a really big deal because it provides a number of avenues or clues by which we might begin to move this country in a better direction.”

Other kinds of social capital matter, too, like rates of volunteering in a community and friendships with people from similar backgrounds. Yet the new study shows that even in places lacking in other kinds of social capital, an increase in cross-class relationships is enough to benefit children’s economic prospects. And it’s this kind of social capital that has decreased as the country has become more segregated by class. In recent decades, people have become more likely to live in neighborhoods and attend schools with people of similar economic status — behavior that social scientists say is driven by anxiety about falling down the income ladder in an age of growing inequality.

“The pressure that parents feel to try to give their kids a competitive advantage is amplified when society is unequal and there’s more to be lost,” said Jessica Calarco, a sociologist at Indiana University who studies inequality in schools and among families. “Our society is structured in ways that discourage these kinds of cross-class friendships from happening, and many parents, often white, are making choices about where to live and what extracurriculars to put their kids into that make those connections less likely to happen.”

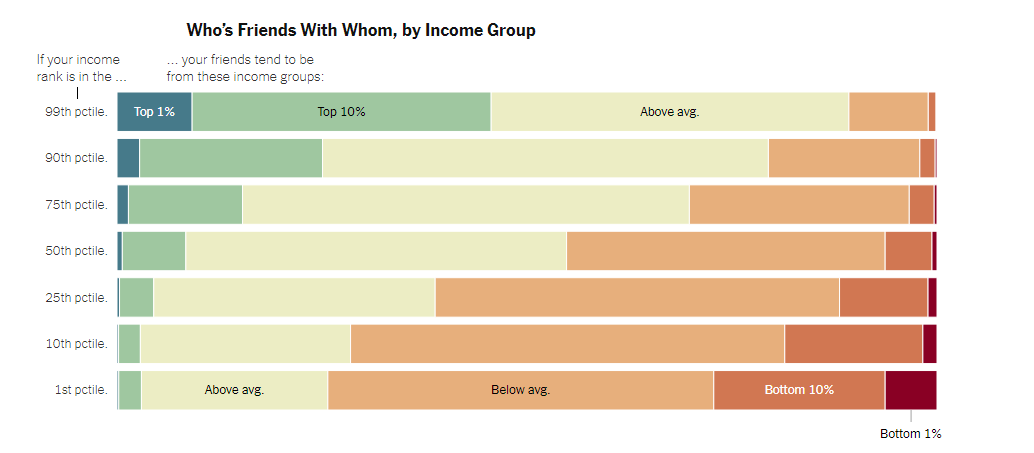

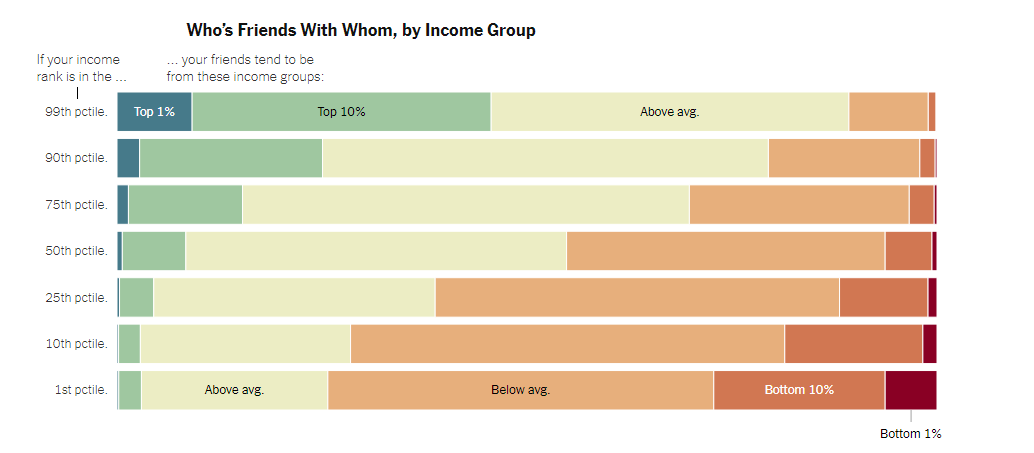

As a result, rich people have mostly rich friends, and poor people have mostly poor friends.

Low-income people are far more likely than high-income people to make friends in their neighborhoods, the study found. But in poorer areas, there are fewer rich people nearby to befriend.

It’s human nature to befriend people who are similar, which is why most cultures have a phrase like “birds of a feather flock together,” Professor Putnam said. Even when people do form cross-class connections, there is evidence in this and other research that they gravitate toward people of the same race.

Ms. Bowie, who is Black and Japanese, said that the friends she made from wealthier families were also Black.

“Just being with Black people who had money was a culture shock,” she said. “But white people with money had a completely different lifestyle. At least with Black people, we had the same sayings, we saw the same movies, our grandparents had the same beliefs.”

The analysis did not directly measure the role of race, which was not provided in the Facebook data. (Though there are techniques researchers use to guess race, the authors of the new study did not use them.) But in more racially diverse places, the study found fewer cross-class relationships.

Race is clearly associated with levels of mobility, a variety of research has shown, including by Professor Chetty’s team. In general, Black people in segregated areas are more likely to experience concentrated poverty and have worse economic outcomes.

“There was speculation that maybe it was about differences in resources, quality of schools, social norms,” he said. “What we show here is places that have large Black populations tend to be more economically disconnected — both Black and white people living there have fewer high-income friends.”

It’s clear that other factors also influence outcomes for Black people in both segregated and integrated areas, he said, including racial discrimination in the labor market and mass incarceration.

But the researchers say their findings on the importance of cross-class relationships are true regardless of race. They found the same relationship — high economic connectedness leading to higher economic mobility — in neighborhoods that were nearly entirely white, Black or Hispanic.

It makes sense that having richer friends will make you step up.

Vast New Study Shows a Key to Reducing Poverty: More Friendships Between Rich and Poor

An analysis of 21 billion Facebook friendships, covering 84 percent of U.S. adults aged 25 to 44, puts cross-class relationships at the heart of income mobility.

www.nytimes.com

Birds of a feather

Social capital, the network of people’s relationships and how they’re influenced by them, has long intrigued social scientists. The first known use of the phrase was in 1916, by L.J. Hanifan, a school administrator in West Virginia. Since then, researchers have found that ties to more educated or affluent people, starting in childhood, can shape aspirations, college-going and career paths.But the new study is the first to show that living in a place that fosters these connections causes better economic outcomes, using a significantly larger data set than other studies, covering 21 billion Facebook friendships.

The researchers limited the data, which did not include names, to active Facebook users. They estimated users’ incomes based on their ZIP codes, college, phone model, age and other characteristics.

For each low-income Facebook user, the researchers determined where the person was currently living, and how many high-income friends they had. That gave them a measure of how economically connected each neighborhood was. Then they compared the new data with earlier research that used tax records to measure how much a particular neighborhood raised low-income children’s economic prospects.

The researchers were also able to link almost 20 million users to both their high school and to their parents on Facebook. Using those ties, they repeated their analysis, this time on high school connections between children of rich and poor parents, to measure the impact of relationships made early in life. They did a similar analysis for teenage Instagram users. And they built on an earlier analysis of siblings who moved at different ages to show that it was the place that made a difference, versus something about the families who moved to those places.

Each analysis had the same result: The more connections between the rich and poor, the better the neighborhood was at lifting children from poverty. After accounting for these connections, other characteristics that the researchers analyzed — including the neighborhood’s racial composition, poverty level and school quality — mattered less for upward mobility, or not at all.

“It’s a big deal because I think what we lack in America today, and what’s been dropping catastrophically over the last 50 years, is what I call ‘bridging social capital’ — informal ties that lead us to people who are unlike us,” said Robert Putnam, the political scientist at Harvard who wrote “Bowling Alone” and “Our Kids,” about the decline of social capital in the United States. “And it’s a really big deal because it provides a number of avenues or clues by which we might begin to move this country in a better direction.”

Other kinds of social capital matter, too, like rates of volunteering in a community and friendships with people from similar backgrounds. Yet the new study shows that even in places lacking in other kinds of social capital, an increase in cross-class relationships is enough to benefit children’s economic prospects. And it’s this kind of social capital that has decreased as the country has become more segregated by class. In recent decades, people have become more likely to live in neighborhoods and attend schools with people of similar economic status — behavior that social scientists say is driven by anxiety about falling down the income ladder in an age of growing inequality.

“The pressure that parents feel to try to give their kids a competitive advantage is amplified when society is unequal and there’s more to be lost,” said Jessica Calarco, a sociologist at Indiana University who studies inequality in schools and among families. “Our society is structured in ways that discourage these kinds of cross-class friendships from happening, and many parents, often white, are making choices about where to live and what extracurriculars to put their kids into that make those connections less likely to happen.”

As a result, rich people have mostly rich friends, and poor people have mostly poor friends.

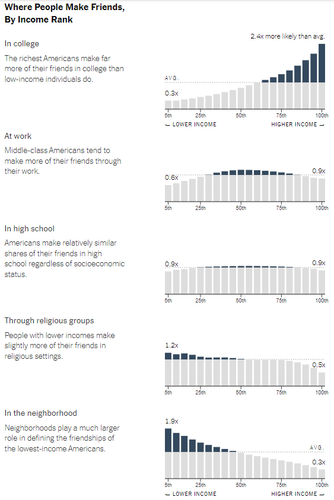

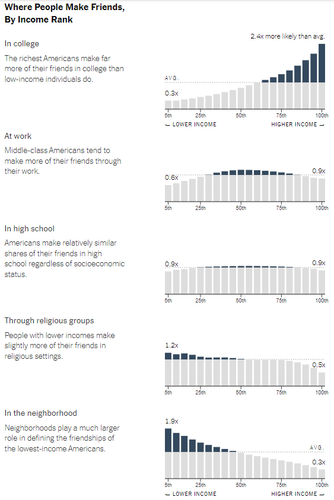

Low-income people are far more likely than high-income people to make friends in their neighborhoods, the study found. But in poorer areas, there are fewer rich people nearby to befriend.

It’s human nature to befriend people who are similar, which is why most cultures have a phrase like “birds of a feather flock together,” Professor Putnam said. Even when people do form cross-class connections, there is evidence in this and other research that they gravitate toward people of the same race.

Ms. Bowie, who is Black and Japanese, said that the friends she made from wealthier families were also Black.

“Just being with Black people who had money was a culture shock,” she said. “But white people with money had a completely different lifestyle. At least with Black people, we had the same sayings, we saw the same movies, our grandparents had the same beliefs.”

The analysis did not directly measure the role of race, which was not provided in the Facebook data. (Though there are techniques researchers use to guess race, the authors of the new study did not use them.) But in more racially diverse places, the study found fewer cross-class relationships.

Race is clearly associated with levels of mobility, a variety of research has shown, including by Professor Chetty’s team. In general, Black people in segregated areas are more likely to experience concentrated poverty and have worse economic outcomes.

“There was speculation that maybe it was about differences in resources, quality of schools, social norms,” he said. “What we show here is places that have large Black populations tend to be more economically disconnected — both Black and white people living there have fewer high-income friends.”

It’s clear that other factors also influence outcomes for Black people in both segregated and integrated areas, he said, including racial discrimination in the labor market and mass incarceration.

But the researchers say their findings on the importance of cross-class relationships are true regardless of race. They found the same relationship — high economic connectedness leading to higher economic mobility — in neighborhoods that were nearly entirely white, Black or Hispanic.

‘A culture of success’

The researchers focused on high schools, one of the few settings where people of all classes make friends at similar rates, and a place where people form lifelong friendships before they start making decisions that may determine their economic trajectories.