mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

Milwaukee's Housing First programs shows how lifting people out of homelessness can improve health, and cut costs

The program, based on a national model, shows how stable, adequate housing can be more important than access to doctors and medicine.

Milwaukee's Housing First programs shows how lifting people out of homelessness can improve health, and cut costs

By Vanessa Rivera, Guy Boulton and Angela PetersonMilwaukee Journal SentinelPublished 7:00 AM EDT Sep. 23, 2022 Updated 7:41 AM EST Nov. 30, 2022

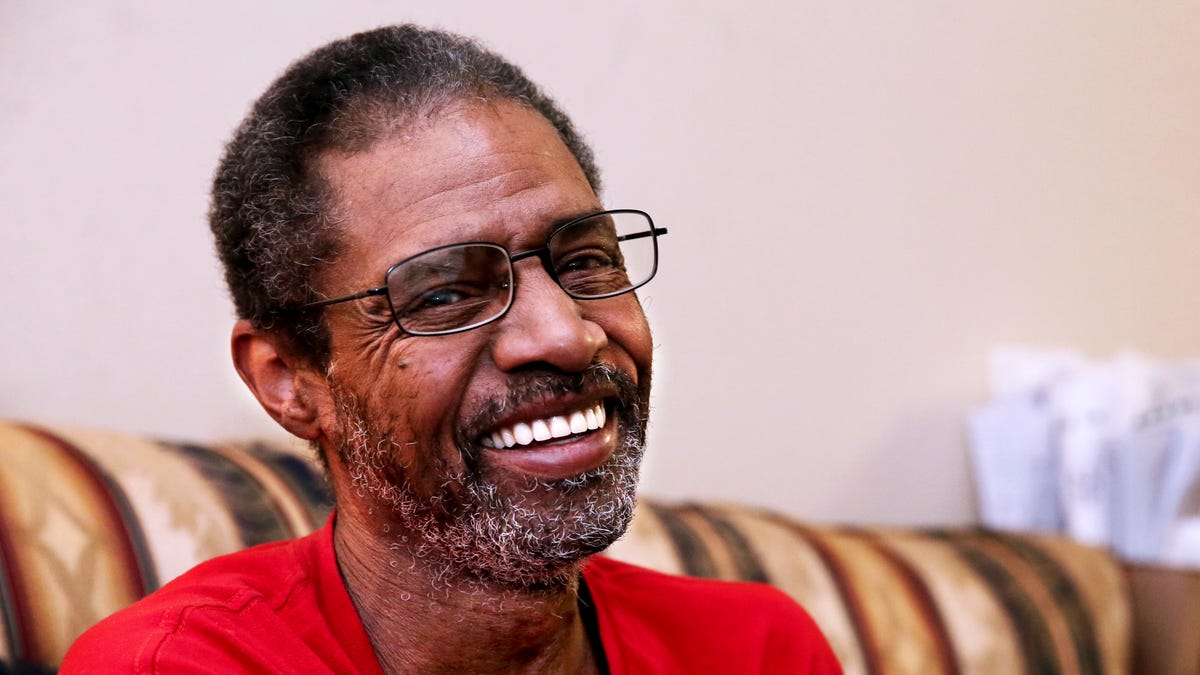

Elijah Edwards begins each day reading Scripture from a Bible as worn from use as his leathered hands are from years of work.

He does this from a modest apartment that helped him rebuild his life, providing a foundation to move beyond addiction and homelessness.

“I’m grateful because this is what God is doing,” Edwards said.

The program, based on a national model, was introduced in Milwaukee County in 2015. It provides permanent housing to people who are homeless without any requirements, such as participation in programs, employment or sobriety. Instead, it offers optional services, such as treatment for substance abuse.

The idea is that people need the stability of a place to live before they can make other changes in their lives.

“It is not necessarily the cure-all for all the layers of the things they are going through,” said Eric Collins-Dyke, assistant administrator of supportive housing and homeless services for the Milwaukee County Housing Division. “But it is the first step to having that stability.”

People have the comfort and stability of waking up in their own bed and walking into their own kitchen.

“They have that each day, before they start the day,” Collins-Dyke said, “as opposed to the constant grind, the daily grind, of surviving on the street and all that comes with that.”

Program aims to reduce hospital visits

The majority of people who are chronically homeless have behavioral health conditions or substance abuse disorders. And the Housing First program was started with $1 million in funding from the Milwaukee County Behavioral Health Division.“Housing is the single greatest need in our community,” said Mike Lappen, its executive director.

The Behavioral Health Division continues to give $1 million a year to the program. The idea is that providing housing to people will reduce emergency department visits and hospitalizations for behavioral health conditions.

The Housing First program — which costs $2 million to $3 million a year — has done that.

The program has reduced costs for state Medicaid programs by $2.1 million a year and for behavioral health services by $715,000 a year for mental health services, according to a brief by the La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

It also has saved the judicial system money by reducing the number of homeless people who are incarcerated.

The Housing First model — which has been used in other communities — is an example of how in some cases spending on social services can save money by lowering health care and other costs.

A three-day stay in a behavioral health hospital, for instance, can cost $4,500 or more. By comparison, the cost of a housing voucher — which limits what a person pays for rent and utilities to 30% of his or her income — averaged about $800 a month, or $9,600 a year, in February 2020.

New approach to help homeless

Homelessness reached crisis levels in the 1980s, prompting a rethinking of how to combat it.Sam Tsemberis founded Pathways to Housing in New York City in 1992, the program that inspired the Housing First model. When Tsemberis came up with the idea, he was working as the director of Project H.E.L.P. (Homeless Emergency Liaison Project) in New York City, an emergency outreach team that serves people who were homeless, mentally ill and a possible danger to themselves or others.

Medical community seeing that better health hinges on social services

Before Housing First, there was no alternative for people facing such challenges. Programs required they be clean and sober before housing. His team took a different approach — to stop dictating and start listening to those they served.

“Pretty much everybody said, ‘I want a place to live.’” Tsemberis said.

His team found homeless individuals to be much more capable than other programs imagined them to be.

“All of that day-to-day, exhausting — figuring it out,” Tsemberis said. “If they can do that, of course they can do an apartment where everything is right between four walls.”

Today, this model has been replicated all over the U.S. and has been adopted in other countries, such as Canada, France and New Zealand.

Injury led to addiction, challenges

A cascade of personal issues led Edwards to the program.Since he was 13, Edwards has waxed and stripped floors and has done tile and grout work. He worked for a company that did remediation for water damage. His favorite job was working as a teen counselor and an assistant physical education director for what is now the Boys & Girls Club from 1970 to 1975.

He also was an intramural basketball coach at the club.

“The exciting part was working with the kids through their hard times,” Edwards said. “Every time I see them, they always call me Coach Edwards.”

Then, in his mid-50s, his life began to unravel, starting with being injured while working and needing hip replacement surgery. He eventually ended up addicted to cocaine and living at the Rescue Mission.

If the weather was good, he said, he would stay in his truck and get high or drink.

A turning point came when Father Steven Block, a friend and spiritual mentor, put him in touch with an outreach worker for the Housing First program.