Migrants Are Settling in Thriving Blue Counties — Not the Red Counties That Need Them

Migrants landing in swing states, and across the country, are gravitating to counties that voted for President Joe Biden in 2020. Much like in previous generations, migrants are headed to places with growing local economies, bolstering the labor force in places that are already thriving.

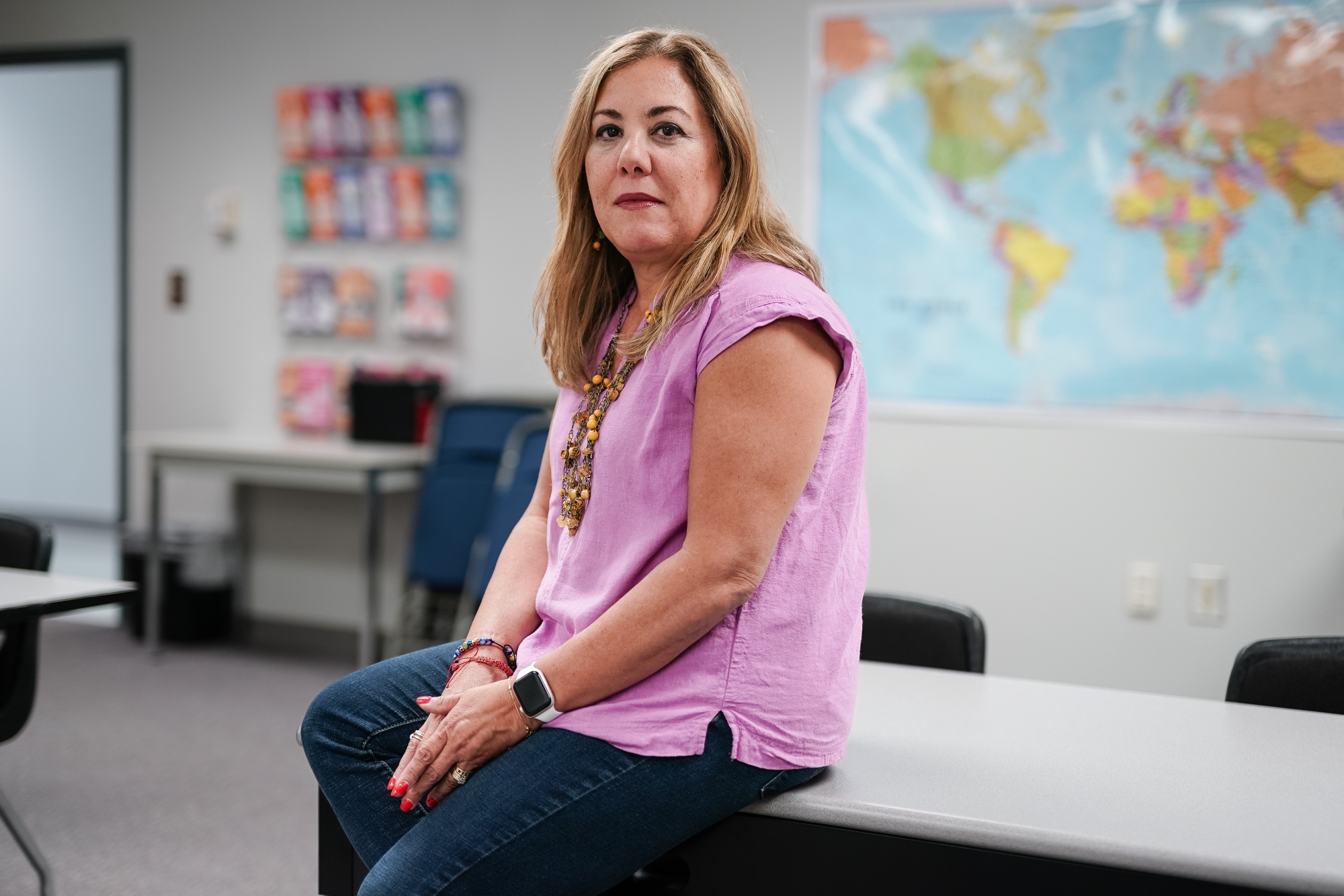

Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, is a Trump stronghold where the politics of immigration are clashing with local economic needs. Photographer: Justin Merriman/Bloomberg

Migrants Are Settling in Thriving Blue Counties — Not the Red Counties That Need Them

By Elena Mejía Shawn Donnan September 16, 2024In this year’s US presidential campaign, few issues figure as prominently as immigration. Voters from coast to coast have seen their communities mired in fierce debates about how to handle an influx of migrants fueled by a record number of border crossings in 2023.

Republican Donald Trump has long put cracking down on immigration at the center of his America First political agenda, using extreme or disproven examples to demonize migrants. Vice President Kamala Harris has had to respond to criticism of the Biden administration’s handling of the issue, even as the inflow at the US-Mexico border has slowed in recent months.

Often lost in all the politicking, though, is a clear accounting of what shape the recent wave of immigration has taken — and what clues that offers about the US economy, including the labor and resource needs of the swing-state cities and towns that are poised to have outsize impact on the election.

Bloomberg News analyzed immigration court data obtained by researchers at Syracuse University that show where the 1.8 million asylum seekers and refugees who landed in the US in 2023 have taken up residence. In past decades, these records for immigration court cases would not have offered as comprehensive a picture of new arrivals. Now, though, more border-crossers are turning themselves in to apply for asylum and, eventually, a work permit, making the data set more exhaustive.

In some places, the prevailing politics are in friction with local economic interests. That creates a messaging challenge for both Harris and Trump as they try to win over voters in key states — and a policy conundrum for local leaders looking beyond the election to their communities’ future.

These newcomers are unlikely to become US citizens before the election, so they won’t be casting ballots of their own. But their arrival will nonetheless reverberate in the presidential contest, and their journeys — as seen in one county that is solid Trump country and another that is a Democratic stronghold — don’t always unfold in the ways partisan campaign cliches would suggest.

Greensburg is the county seat of Westmoreland County, which has seen a steady decline in its population over the past half century. Photographer: Justin Merriman/Bloomberg

At Scott Electric, a wholesale distributor for electrical products located in the exurbs of Pittsburgh, business is so good that the company is expanding its warehouse space, says General Manager Chaz Boggs.

But in Westmoreland County, where the population has been in decline for decades and the recovery from the pandemic recession has been slow, his company has struggled to fill vacancies and retain workers.

One answer has been Ukrainian refugees brought to the area through a relocation effort for migrants authorized to work in the US that is run by a local Catholic diocese. Boggs now employs two such workers and would like to hire more. Some 150 Ukrainians are on a waitlist with the diocese to make a similar move.

“It is a win-win situation. For them and us,” Boggs says.

Westmoreland, which through the 19th and 20th centuries turned coal into a manufacturing-driven regional economy that once attracted companies such as Alcoa, Sony and Volkswagen, has weathered decades of deindustrialization that led to a steady exodus of people. And for years local leaders have been plotting how to attract more residents, with mixed results. The county’s population is about 10% smaller today than it was at its peak in 1979.

Westmoreland was the destination for just 142 migrants with cases pending in immigration court in 2023. And the politics of the region may preclude that from getting much larger.

Local Republican elected officials have this year worked to get the county, in which Trump took 63% of the vote in 2020, taken off a list of sanctuary communities kept by the Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank that advocates for tougher border policies. That became an issue because of Republican moves in the state legislature to crack down on cities and counties identified as sanctuaries and local complaints from Trump supporters.

As of last month, Republicans had spent over $150 million this year to fund immigration-focused ads that air in swing-state TV markets, according to AdImpact, an organization that tracks political ads. Almost two-thirds of that money comes from the Trump campaign and two Trump-supporting super PACs — MAGA Inc. and Preserve America PAC.

And those groups have spent more money on immigration-focused ads than on any other issue, with almost half their spending in swing states going to Pennsylvania and Georgia. In Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, for example, 73% of their total spending went to ads with an immigration focus. One says “Pennsylvania is paying the price” after Biden “let all these people in.”

The narratives spun in those broadcast messages don’t necessarily reflect reality.

One of the refugees working in Scott Electric’s Greensburg warehouse is Andrii Babak, who owned a trucking company in Ukraine that he closed when the war started, donating some of his trucks to the Ukrainian military and selling another so that he could leave the country.

“I see a future in this country,” Babak said. “I like this country.”

Andrii Babak moved to Greensburg in 2023 as part of a resettlement program for Ukrainian refugees administered by the local Catholic diocese that matches newcomers with employers. Photographer: Justin Merriman/Bloomberg

He joined his girlfriend, Dariia Savenko, who months earlier crossed into the US from Mexico with her two children and lodged a refugee claim. Savenko took this approach after she says she was twice denied visas to come to the US.

In Babak’s $19.50 per hour job, he has found at least a start and a way to practice the English he is still learning. Starting over is not easy, but one day, Babak hopes, his job in the warehouse might grow into a supervisor role that pays more. He has a second job doing maintenance for the diocese.

Meanwhile, Savenko is working at a nursing home and aims one day to get her certification as a nursing assistant in a place that, like many in America, is struggling with a shortage of both nurses and nursing home staffers. Her two daughters have scholarships to the local Catholic schools. Both Babak and Savenko are authorized to work in the US.

When she calls friends or her father back in Ukraine, Savenko tells them that while it’s different from the life they once lived, she and her daughters are in Westmoreland County to stay. “I feel like I am home,” she says.

The program that brought Babak and Savenko here was rushed into existence by Bishop Larry Kulick, who sees immigrants as the pragmatic answer to some of Westmoreland’s challenges.

“I want to welcome people who need a place and give them an opportunity for the American dream,” Kulick said.

they're literally doing that. You in a thread that is touching on just that. TF?

they're literally doing that. You in a thread that is touching on just that. TF?