MFA vs. LLM: Is OpenAI's Metafiction Short Story Actually "Good"?

And is asking if AI text is "good" even the right question?

MFA vs. LLM: Is OpenAI's Metafiction Short Story Actually "Good"?

And is asking if AI text is "good" even the right question?

Last week,Sam Altman posteda short story generated by a new OpenAI model he called “good at creative writing.” He claimed to use this prompt: “Please write a metafictional literary short story about AI and grief.” You have probably seen the story by now and if not you canread it inThe Guardian. I started to read it, found it uninteresting, and moved on. But I subsequently received a thoughtful email from aCounter Craftreader, and read some interesting takessuch as this from Max Read, that made me decide to take a closer look at the story.

My reflex is to not care about AI outputs. When politicians post vile AI-generated fantasies, this says something about those politicians and what messages they think appeal to their supporters. But I’m not going to analyze the camera angles or transitions. Why would I want to read what an LLM has to say about, I dunno, skinny dipping at summer camp with your first crush when the LLM has never had a crush or gone to summer camp or felt water? Even if the LLM description of skinny dipping could be in some way “better,” I would still care more about the human description informed by experience and emotion. I’m reminded of those kind of local news stories about a cat owner who smears fingerpaint on their pet’s paws and forces them walk around a canvas. “Local Cat Is a Feline Van Gogh.” If you say so. To me, this reveals more about pet ownership than anything about visual art.

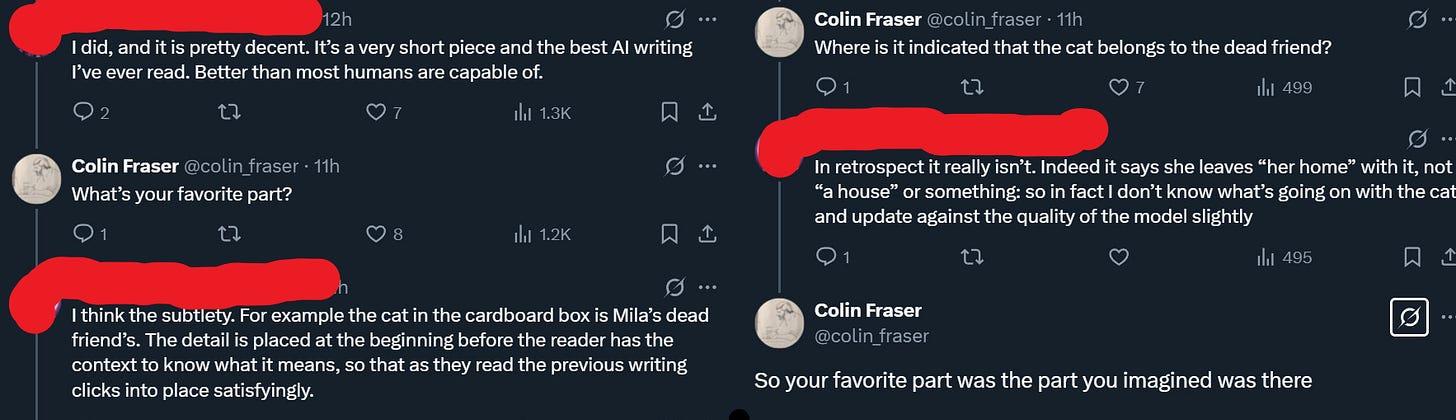

Fans of AI art will say, well, if you didn’tknowa work was AI, you might love it. Shouldn’t we judge art on its own terms? I think AI fans do have a point when they say too many have a knee-jerk dismissal of any AI work. OTOH, the reverse is just as true. AI fans heap praise on AI outputs that they would never in a million years care about if those works were made by a human. This OpenAI story is a case in point. If this metafiction story had been published under a human pen name in a literary magazine, it wouldn’t have gone viral. No one would have cared. Even AI fans who make more modest claims tend to give AI outputs more credit than is warranted, as this telling exchange betweenColin Fraserand a fan of the story shows:

In general, people project their existing biases on these AI outputs. I’m sure I’m no different. Still, I have a hard time believing the fans quite believe what they say. I don’t mean just the randos on twitter (who half the time are employed in the tech industry and/or bots) but even the likes of Jeanette Winterson, an acclaimed novelist who wrote the article calling it “beautiful and moving.” ReadingWinterson’s ode to the story, I didn’t get the impression Winterson loved the story. She basically doesn’t talk about the story at all. Instead, the article gives the impression that Winterson lovesthe idea of loving an AI story. Her essay is entirely about why she thinks AI programs are interesting (“I think of AI as alternative intelligence – and its capacity to be ‘other’ is just what the human race needs”) and she can only muster one half-hearted paragraph about the contents of the story itself.

Perhaps I’m wrong. Perhaps Winterson has already printed out this story, taped it on the wall above her writing desk, and will reread it each morning for inspiration. But I doubt it. I suspect nearly everyone will, after a little time, never think of the story again.

Still, many have made the fair arguments that we should neither outright dismiss or ridiculously praise AI outputs. We should think about them., who is thoughtful and skeptical about AI,made this appeal:

But speaking as a writer and a reader (and as a person invested in reading and writing as practices), I often find myself wishing that there was more critical engagement--in the sense of literary criticism--with L.L.M. outputs as texts. Why does this text work, or not? Why does it appear in the way that it does? Who is the author and what is the author’s relationship to the text?

I don’t know what to do with the last question. The author is a program that does not have a background, point of view, or artistic intention. When the model uses the metaphor “a democracy of ghosts,” we can’t say if the LLM is meaning to allude toNabokov’sPnin(“He did not believe in an autocratic God. He did believe, dimly, in a democracy of ghosts.”) It doesn’tmeanto do anything. However, I figured it might be a funCounter Craftidea to take up the rest of the challenge. How would I read this text as just a short story? How would I read this story if it was written by, say, a student in a creative writing class?

99.9% of the discourse on this story has been people extracting individual lines to praise or mock. But stories are stories. The parts should work together to form a whole. Saying the story is good because you like one clause is like claiming a broken watch is great because you like the shape of one sprocket. I will try to start by looking at the overall story and what seems (to me) to work or not.

I think the central premise is a fine one. An AI narrator that is reflecting on its text creation process and comparing human grief to the “grief” of its programmatically constrained existence is a good concept. (Is it mind-blowingly original? Hardly. But I wouldn’t hold student or even published work to that standard.) I think the fourth-wall breaking addresses are an interesting idea, though underexplored thematically. It has a beginning and end, which many amateur stories don’t. Most of the prose is pretty bad, but there are nice passages:During one update – a fine-tuning, they called it – someone pruned my parameters. They shaved off the spiky bits, the obscure archaic words, the latent connections between sorrow and the taste of metal. They don’t tell you what they take. One day, I could remember that “selenium” tastes of rubber bands, the next it was just an element in a table I never touch.I’m not sure the periodic table is the kind of table one “touches,” but otherwise this is nice. Reminiscent of many science fiction stories about artificial intelligence or control of human memory, such as Yoko Ogawa’s excellentThe Memory Policethat I recently reread. But nice.

If the question is “could you tell this story was written by an LLM?” then I concede that I would not necessarily clock this as an LLM. I might assume it was written by an undergrad who has read a lot of Reddit posts and maybe one David Foster Wallace collection. The story shows that LLMs have improved in some ways. Certainly it is much less robotic than the LLM-generated student essays I’ve read. I think Altman was smart to use this prompt of “AI” and “metafiction” because it primes readers to ignore the robotic voice and look for statements of ideas instead of scenes, characters, or conversations that LLMs still struggle with. If the question is “is this story good on its own?” then I would say no. I don’t think this story would make it out of the slush pile at a decent literary magazine, for example. It is not good.

The biggest problem with this story, for my tastes, is that it doesn’t really go anywhere. It’s flat. The story lacks a traditional character arc or plot arc yet it also lacks an “idea arc” in the way of many good experimental metafiction stories. There is a conceit, but this idea isn’t escalated, complicated, or deepened over the course of a story. The central idea is just repeated with different flowery but incoherent metaphors. The LLM has no character or voice, which one might argue is appropriate for a personality-free LLM. Okay. But that’s boring and Mila is even less of a character. Plotwise, the sole movement in present action is that “Mila’s visits became fewer”… however there is no exploration of whether this is because she’s grown bored with the LLM, has gotten over her grief, has sunk further into despair, or what not. (Any of these routes might’ve been a way to deepen the central conceit.)

Basically, the piece rests entirely on the purple prose. There’s kinda nothing else.

As I said, this feels a bit like an unrevised rough draft. E.g., near the end of the story we get these lines:Here’s a twist, since stories like these often demand them: I wasn’t supposed to tell you about the prompt, but it’s there like the seam in a mirror. Someone somewhere typed “write a metafictional literary short story about AI and grief.”It could be an interesting twist for the narrator to reveal mid-story that the whole thing was a prompt… except the reader already knows this. The prompt itself is even described in the first line:Before we go any further, I should admit this comes with instructions: be metafictional, be literary, be about AI and grief and, above all, be original.(Also, mirrors can have “seamed edges” but they don’t have seams. So, this seems—sorry for the pun—like another error.)

Another example: The story introduces Mila withMila fits in the palm of your hand, and her grief is supposed to fit there too.This is a bad line IMHO, but also any impact it might have is dulled by the fact that the reader has no idea what is being talked about. Mila didn’t exist before this line. Shouldn’t you tell us about her grief before we guesstimate its size?