Malcolm X as Visual Strategist

By Maurice Berger Sep. 19, 2012 Sep. 19, 2012

5

- Malcolm X, the national spokesman for the Nation of Islam, stands as one of the great meta-images about photography — an astute commentary on our insatiable hunger for pictures. Taken in Los Angeles in May 1963, the photo depicts the civil rights leader and his associates as they await the verdict of an all-white jury deliberating the fate of 14 Black Muslims accused of assaulting police officers. The pictorial magazines and tabloid newspapers they voraciously read to pass the time nearly crowd out the image.

If Flora’s photograph speaks to the country’s obsession with visual media, it tells another, interconnected story about Malcolm’s passionate engagement with photography. The men in the picture are focused on articles about the Nation of Islam. The Life magazine story that engrosses Malcolm, for example, was typical of the derisive coverage of the Black Muslims in the mainstream press: “The White Devil’s Day Is Almost Over: Black Muslim’s Cry Grows Louder,” screams its headline.

Malcolm X was one of the most media-savvy black leaders of the period. By the time of his assassination in 1965, he was also one of the most photographed (and televised, appearing on hundreds of local and national interview programs). Handsome, charismatic and articulate, he provided the mainstream news media with a continuing and histrionic story that would enrapture its readers: a burgeoning black community calling for self-determination, racial separatism and independence to be achieved by “any means necessary,” including violent insurrection.

In turn, the news media afforded him a national platform for espousing a radical worldview, one that rejected the nonviolent practices and integrationist goals of the mainstream civil rights movement. (Shortly before his death, Malcolm’s view of the latter grew more conciliatory.)

For more positive reporting, Malcolm X could depend only on the Nation of Islam’s weekly newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, and, to a lesser extent, the Negro press. The mainstream news media, stoked by his fierce, sometimes inflammatory rhetoric and its own anxieties around race, afforded little more than negative and sensationalistic coverage, much like the Life article featured in Flora’s photograph. If conventional news outlets typically portrayed the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as the “angel of light,” as the sociologist Algernon Austin wrote, Malcolm had become their villainous “angel of darkness.”

While Malcolm viewed the “white press” as more or less a lost cause — its coverage remained largely negative until the day he died — he nevertheless engaged it and, at times, outsmarted it. The public’s trust of and faith in visual media, and its dominant role in shaping public opinion, made it a powerful outlet for reaching his target audience: African-Americans disillusioned with the mainstream civil rights movement.

Many blacks at the time rejected the Nation of Islam’s religious orientation, fundamentalism, political extremism and cultural insularity. But many were also skeptical of the mainstream movement; a 1963 poll by Newsweek reported that more than a third of African-Americans were “resigned to the possibility that they may have to fight their way to freedom.” It was the purpose of Malcolm’s media campaign to motivate these people. And it was the photograph that served as one of his most effective motivators.

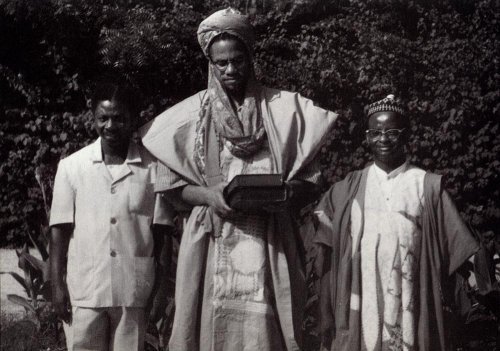

A keen steward of the Nation of Islam’s visual representation, Malcolm X often carried a camera, his way of “collecting evidence,” as Gordon Parks once observed. He relied on photographs to provide the visual proof of Black Muslim productivity and equanimity that sensationalistic headlines and verbal reporting often negated. When photojournalists visited the community, he tried to steer them toward the kinds of affirmative images — shots of contented family life, children at play and school, and thriving businesses and institutions — that might subtly ameliorate the negative texts that he knew would inevitably accompany them.

In her book “Flashback: The 1950s” (Alfred A. Knopf, 1978), the photographer Eve Arnold writes of Malcolm’s passion for getting the picture right. From 1959 through 1960, Arnold, on assignment for Life, shot hundreds of images for a photo essay about Malcolm and the Nation of Islam. While she won Malcolm’s trust, he continually inserted himself into her process, guiding her through Black Muslim enclaves in Chicago, New York and Washington and even, at one point, walking out 10 women in traditional Black Muslim attire and posing them for a photo shoot. Arnold, a wily negotiator, acquiesced. “Malcolm set up the shots and I clicked the camera. It was hilarious,” she wrote of his zeal.

Well before the rise of photo ops and People magazine, he endeavored, with considerable sophistication, to prepare himself — and the community he led — for the penetrating, and often unforgiving, eye of the news media.

But when Arnold attempted to photograph Malcolm framing a photo with his hands, “to catch him in the act,” as she put it, he demurred. It was the wholesomeness of the community, and not his role as image maker, that he hoped Arnold’s photographs would reveal. (Life pulled the photo essay as it was going to press. Some of the photographs were published in Esquire the following year.)

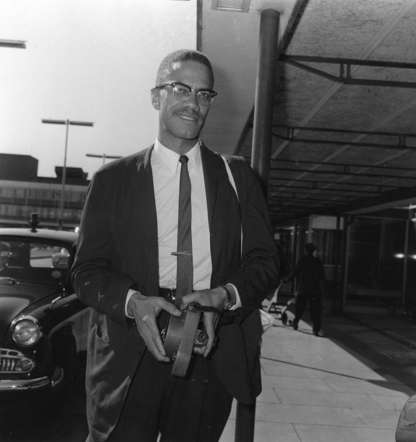

If Malcolm was a talented visual strategist behind the camera, he was nothing less than a prodigy in front of it. Well before the rise of photo ops and People magazine, he endeavored, with considerable sophistication, to prepare himself — and the community he led — for the penetrating, and often unforgiving, eye of the news media. He crafted every aspect of his camera persona, from the cool self-confidence he exuded in still images to the urbane speaking style and command of ideas that were the hallmarks of his television appearances.

In “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” he recounted the ways he altered his outward appearance, from clothing to hairstyle, to transform himself from Nebraska country kid and small-town Michigan teenager to Boston “home boy,” and finally to national political and religious figure. Taking charge of his image helped Malcolm to define himself before the news media could define him. It also afforded him the opportunity, by the example he set, to reverse stereotypes and change minds.

In the end, it is the precision and sophistication of Malcolm’s self-presentation that reads most vividly in Flora’s photograph: the fashionable, well-tailored clothes, the chic eyeglasses, the relaxed yet formal posture, and the refined hand gesture, details meant to convey both composure and authority.

No matter Flora’s motivation for taking the picture, his subject, much as always, succeeded in getting his message across. And through the myriad ideas he communicated through photographs, Malcolm X transformed the Nation of Islam — increasing its membership by tens of thousands and allowing its leaders to influence African-American public opinion for decades to come.

Got his picture up on my wall (pause)

Got his picture up on my wall (pause)

Used it as a tool to affect the narrative.

Used it as a tool to affect the narrative.