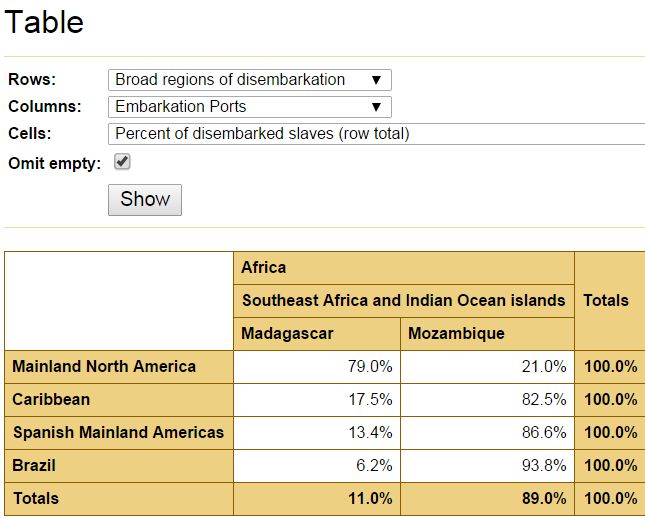

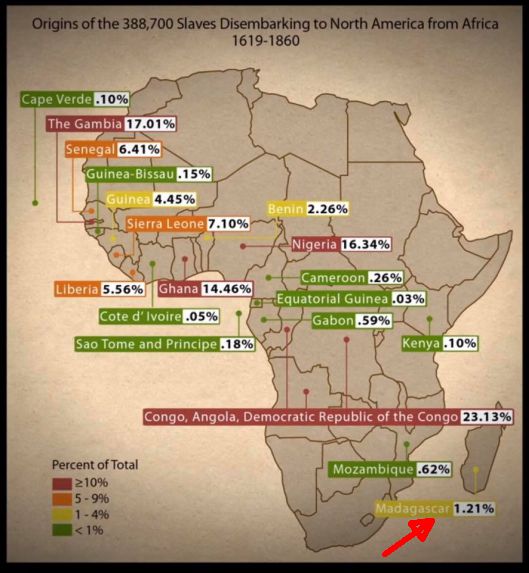

Every now and again I would see a DNA result comeback as Madagascar, which isn't particularly odd given I've read enough / seen enough data that shows African Americans also have populations that came from there. That said I randomly got the urge to really look into that vector of populating the U.S. ...figured I'd dump some preliminary data I found.

Dr. Wendy Wilson-Fall of Lafayette University

Memories of Madagascar and Slavery in the Black Atlantic

By Wendy Wilson-Fall

Foreword by Michael Gomez

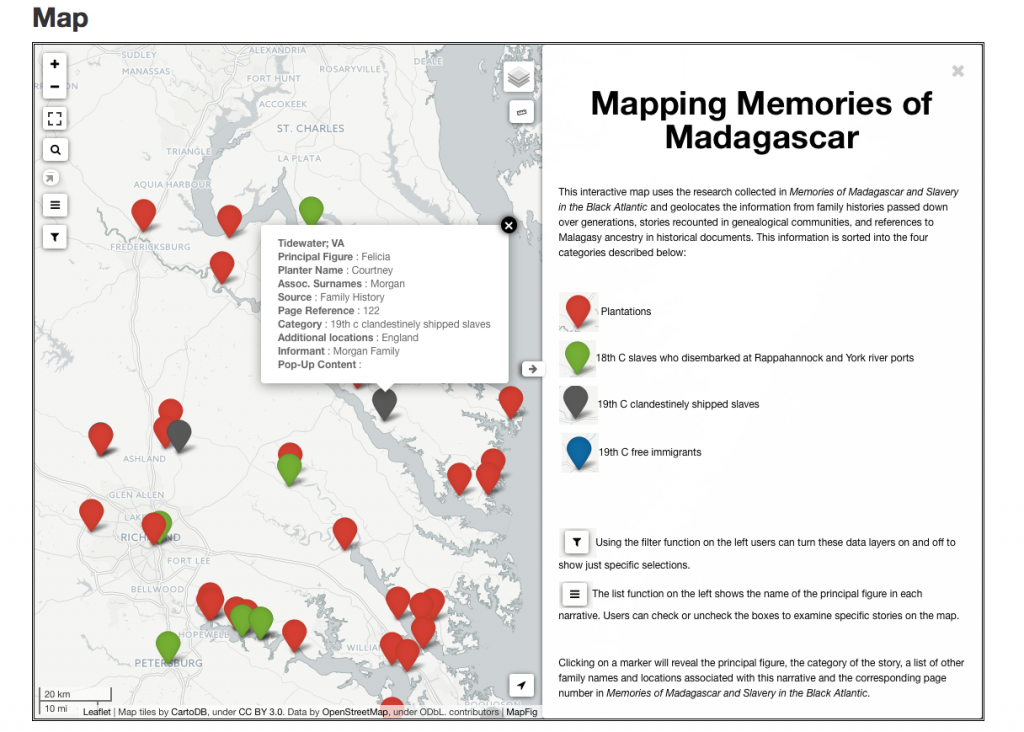

OK. I’m going to talk about four or five different periods, although in my particular research, I’ve really focused on three of those periods. But I would say that the first period was the 17th century where you have records of Malagasies being brought in as slaves, both to Canada and to New York under the Dutch. And at that time it was the Philips family who were extremely active in bringing slaves from eastern Madagascar to New York, presumably to sell them in the northeast area, perhaps to Canada, perhaps down as far as Delaware. There’s certainly a record of that, although I haven’t seen any reckoning of the numbers of people. But then you get to the 18th century and you have to see this also as an evolution of the British attitude toward Americans having access to East Indian Ocean trade. So it’s a little bit like what caused the Boston Tea Party. Americans were not allowed to trade in the Indian Ocean. If they wanted something that was an Indian Ocean product they had to buy it in London or Bristol. They weren’t supposed to go directly, but because of their lobbying, there were two periods—I think between 1670 and 1693, and then 1712 to 1721 or so, when the British parliament actually legalized direct trade to the Indian Ocean. So, one of the results of that was several boats that left with the explicit intention of going to Madagascar to pick up labor and whose investors were mostly the big Virginia planters like Robert King Carter and John Randolph. John Baylor would be another. So they invested; they worked out the itinerary with their contemporaries, their financial advisors in London and Bristol, and the ships went directly to Île Sainte-Marie (Saint Mary’s Island) in the northeast of Madagascar. We have one record that between 1719 and 1721, 1400 people from Madagascar were imported into Tidewater, Virginia, which is actually a very big number for three years. It works out that almost about every 22nd or 25th captive would have been of Malagasy origin in that region.

If you look at the other research on Virginia, for example by Lorena Walsh, who’s a historian at Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, you realize that not only were they coming to Virginia, but of those 1400, fully a thousand of them went to one major river port, which was the York River. This suggests that there was a critical mass of people of Malagasy origin in a fairly delimited geographic area, who were owned and managed by a rather small and rarified group of people, which increases the likelihood that they would have met each other carrying out tasks for the various plantations they ended up on—perhaps seeing each other as messengers, as horse drivers, as boatmen. So those people were able to sustain at least some idea about having ancestors from Madagascar, and that Madagascar was a unique geographic place. It was not the same as the African continent.

The next group of people show up in the 1820s, and from the 1820s on, it’s kind of ironic. It’s the people coming in as slaves from 1719-1721 for whom we have a record of their arrival, because they were unfortunately classed as commodities. Even though we don’t have lists of their names, we know what ships they were on, we know who the captains were, and to a great extent, we even know who bought them. So we can say they were most likely at X, Y and Z plantations. That wasn’t true later.

The people who came in the 1820s to the 1830s belong to two different groups. One group I class as freed merchants. These were people who had white sponsors—you could say a trading partner or boss. They worked on their ships or they were sailors on their ships or perhaps they were linked to a particular commodity that these people were importing from the Indian Ocean. I have stories like that from South Carolina, from Alabama, from my own family in Maryland. And it appears that at least two of these families refer to Cape Town, South Africa, which makes sense because most Indian Ocean trade had to come through Cape Town. I have this category of people who appear to be free, at least by the time they came to the U.S. I do admit that it’s possible that some of them may have been what they call affranchi (manumitted) either in Mauritius or in Cape Town, so that’s always a possibility. In any case, they show up in the U.S. as free people.

The second group is people who appear to be brought in through an illegal, clandestine slave trade. And here’s the reason I think this. While I was collecting stories, I used the Internet, genealogical sites, and word of mouth, and I kept getting these stories where people only counted back to the 1830s. At first I thought, “No, this is impossible because the Atlantic slave trade was outlawed in 1808, and most of that was achieved by 1812, 1814, 1817. Could this be true? Maybe these people have confused the way they’re counting back their generations.” But when I got so many of these kinds of stories, I realized that I just had to be a little bit more flexible and allow the possibility that it was me who didn’t understand, that there’s something here that maybe hasn’t come to light before. And I was even able to identify geographic clusters of people in the United States, geographic clusters of stories of people who have ancestors who arrived as slaves after 1825. One difference with this group is that they don’t seem to have arrived in a great big boat full of people from Madagascar. They seem to have been isolated in areas where there aren’t other people from Madagascar, so they ended up sort of on their own in Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio. Those are all areas where these stories are coming from.

Afropop Worldwide | Wendy Wilson-Fall on Malagasy Americans