get these nets

Veteran

Lincoln University president seeking to merge two university identities

Lincoln University has long held two identities

The historically Black university has also served as a regional institution of higher education in Mid-Missouri for decades. The result is one of the most diverse universities in the nation.

University President John Moseley is looking to support that dual mission, calling Lincoln's diversity a strength and a weakness.

"I don't know an institution in the country that wouldn't want our diversity," Moseley said. "Yet some struggle and want to be different from who we are and how we are, regardless of what side they sit on. And it makes no sense to me."

Lincoln University President John Moseley is shown with his daughter, Jillian, and wife, Crystal. (Courtesy/Lincoln University)

Lincoln had an entirely Black student population in 1954, Moseley said.

While the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education ended racial segregation in public schools and introduced Black students to many predominantly white schools, it had the reverse effect and introduced white students to Lincoln.

Within three years, Lincoln became 33 percent white. And within six years, the Jefferson City Community College closed, and Lincoln became a majority white institution.

Although it has maintained its HBCU heritage and mission, Lincoln remained a majority white institution from 1960-2017. Some years, the student population was 80 percent white, Moseley said.

Now, Moseley said students who identify strictly as African American make up about 43 percent of the university's population and students who identify strictly as white make up about 40 percent of the student population. When accounting for multiple races, he said the figures stand around 60 percent non-white and 40 percent white.

"We're one of the most diverse institutions in the country," he said. "In my opinion, our diversity is our greatest strength and our biggest challenge."

Diversity is an important part of the education Lincoln provides, Moseley said, because it prepares students for life beyond college.

He said the university's diversity lends itself to learning about the experiences of others and instills a confidence in students that allows them to be themselves in spaces with people who don't come from similar backgrounds.

"If we have a nursing major from Russellville, Missouri, likely it's going to be a white student," Moseley said. "If that nurse ends up in St. Louis and she's working in a hospital in St. Louis and an African American comes in because they're in need at that point, I'd like to think Lincoln University has helped that student develop a cultural competency that allows them to treat that patient with the respect and dignity that everyone of us have come to expect."

The dual role is also a challenge, however.

Moseley said there's an ever-present consciousness to consider how decisions will be taken by different students, faculty, staff and alumni who may have expectations for Lincoln.

That hasn't been a significant consideration at the previous HBCUs and universities Moseley has worked at, he said, but their student populations weren't as diverse.

Moseley said he's also conscious of the fact he's the first white university president since Richard Baxter Foster, the first principal of the Lincoln Institute in 1866.

But I also know how I was raised as a person and the things that I believe in as a person, and the values that I hold," he said. "And I think that many of those are shared by people regardless of our backgrounds."

Moseley and his administration use the crossroads of being an HBCU and a regional institution to shape decision-making, he said.

The dual identity discussion is most prevalent in recruitment and admissions, Moseley said. Some want the university to focus on recruiting students from local high schools, and others want Lincoln to concentrate on national recruiting.

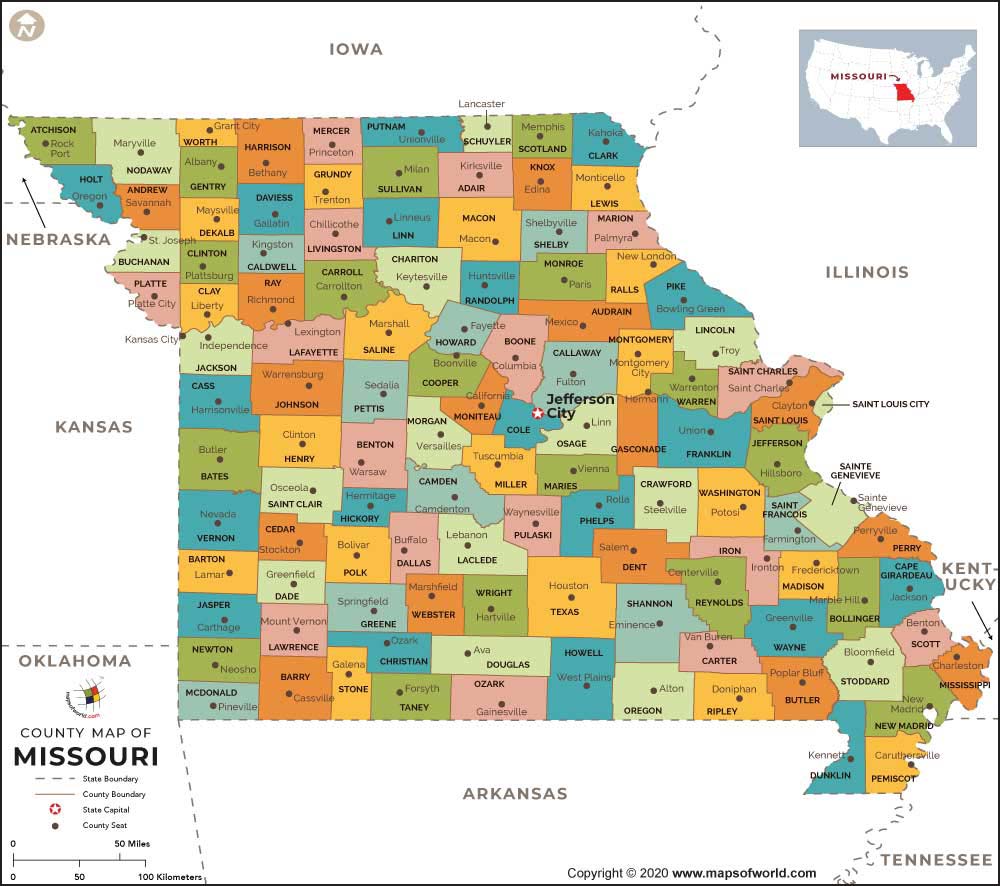

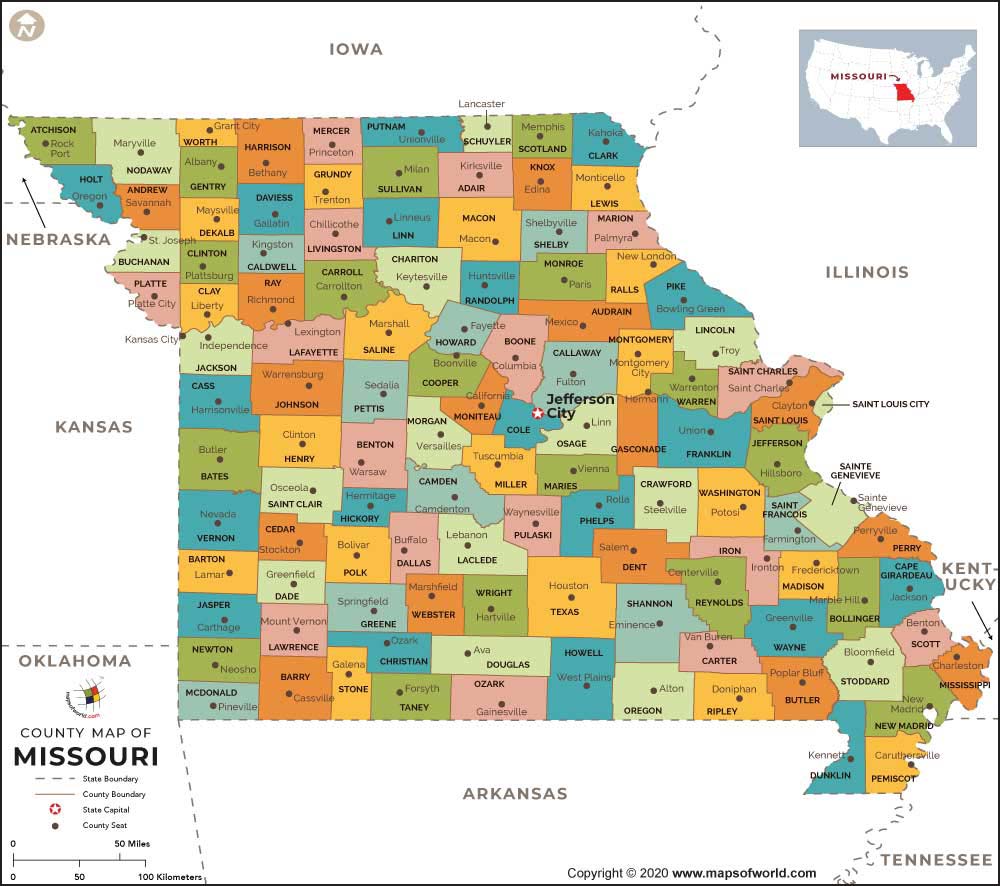

Cole County is 80 percent white and all neighboring counties -- except Boone County (76 percent white) -- are at least 85 percent white, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

"For a long time, pre-dating my appointment as president, there's just been this belief that if you recruit locally you're turning away from your mission as an HBCU, or if you recruit nationally, you're turning away from your responsibility as a state institution that is a regional institution," Moseley said.

He said there's no reason the university can't do both.

Lincoln University has long held two identities

The historically Black university has also served as a regional institution of higher education in Mid-Missouri for decades. The result is one of the most diverse universities in the nation.

University President John Moseley is looking to support that dual mission, calling Lincoln's diversity a strength and a weakness.

"I don't know an institution in the country that wouldn't want our diversity," Moseley said. "Yet some struggle and want to be different from who we are and how we are, regardless of what side they sit on. And it makes no sense to me."

Lincoln University President John Moseley is shown with his daughter, Jillian, and wife, Crystal. (Courtesy/Lincoln University)

Lincoln had an entirely Black student population in 1954, Moseley said.

While the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education ended racial segregation in public schools and introduced Black students to many predominantly white schools, it had the reverse effect and introduced white students to Lincoln.

Within three years, Lincoln became 33 percent white. And within six years, the Jefferson City Community College closed, and Lincoln became a majority white institution.

Although it has maintained its HBCU heritage and mission, Lincoln remained a majority white institution from 1960-2017. Some years, the student population was 80 percent white, Moseley said.

Now, Moseley said students who identify strictly as African American make up about 43 percent of the university's population and students who identify strictly as white make up about 40 percent of the student population. When accounting for multiple races, he said the figures stand around 60 percent non-white and 40 percent white.

"We're one of the most diverse institutions in the country," he said. "In my opinion, our diversity is our greatest strength and our biggest challenge."

Diversity is an important part of the education Lincoln provides, Moseley said, because it prepares students for life beyond college.

He said the university's diversity lends itself to learning about the experiences of others and instills a confidence in students that allows them to be themselves in spaces with people who don't come from similar backgrounds.

"If we have a nursing major from Russellville, Missouri, likely it's going to be a white student," Moseley said. "If that nurse ends up in St. Louis and she's working in a hospital in St. Louis and an African American comes in because they're in need at that point, I'd like to think Lincoln University has helped that student develop a cultural competency that allows them to treat that patient with the respect and dignity that everyone of us have come to expect."

The dual role is also a challenge, however.

Moseley said there's an ever-present consciousness to consider how decisions will be taken by different students, faculty, staff and alumni who may have expectations for Lincoln.

That hasn't been a significant consideration at the previous HBCUs and universities Moseley has worked at, he said, but their student populations weren't as diverse.

Moseley said he's also conscious of the fact he's the first white university president since Richard Baxter Foster, the first principal of the Lincoln Institute in 1866.

But I also know how I was raised as a person and the things that I believe in as a person, and the values that I hold," he said. "And I think that many of those are shared by people regardless of our backgrounds."

Moseley and his administration use the crossroads of being an HBCU and a regional institution to shape decision-making, he said.

The dual identity discussion is most prevalent in recruitment and admissions, Moseley said. Some want the university to focus on recruiting students from local high schools, and others want Lincoln to concentrate on national recruiting.

Cole County is 80 percent white and all neighboring counties -- except Boone County (76 percent white) -- are at least 85 percent white, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

"For a long time, pre-dating my appointment as president, there's just been this belief that if you recruit locally you're turning away from your mission as an HBCU, or if you recruit nationally, you're turning away from your responsibility as a state institution that is a regional institution," Moseley said.

He said there's no reason the university can't do both.