“

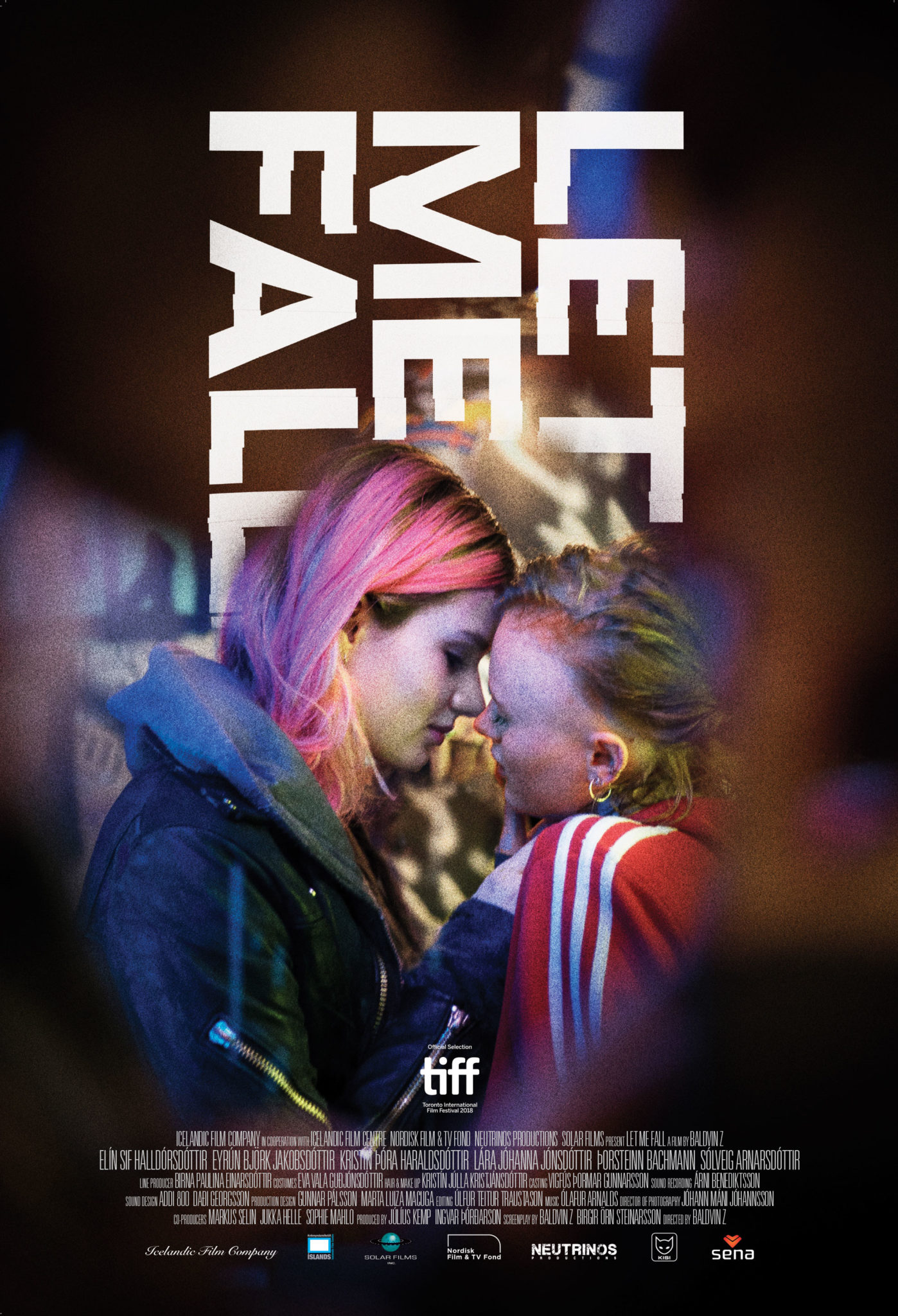

Let Me Fall” is a harrowing look at addiction that stands out amid an autumn filled with films about junkies and their families. Again touching a domestic nerve as he did with “Life in a Fishbowl,” Icelandic auteur

Baldvin Z’s drama tells the story of two teenage girls and their descent into the hellish depths of substance abuse. Like Z’s two previous features, it is strongly acted and sensitively directed. It is also remarkable for its unflinching gaze at the abuses the protagonists suffer to satisfy their habits, and for its compelling cinematic style. “Fall” opened in Reykjavik on Sept. 7, far out-grossing “The Nun” in its first week, and is still going strong.

Like Amazon’s awards-buzz title “Beautiful Boy,” “Let Me Fall” is also based on true stories and considerable research in the addict community. And like “Beautiful Boy,” it unfolds in a nonlinear fashion, cutting between the girls as thrill-hungry teenagers and their lives some 12 years later, when they are both broken adults. But in “Fall,” parents and extended family play a lesser role, although Magnea’s father (Thorsteinn Bachmann) is a sympathetic if ineffectual figure. The focal point is the relationship between the girls and how a betrayal and its repercussions change both their lives.

From the high-octane opening minutes in which 15-year-old Magnea (the mesmerizing Elín Sif Halldórsdóttir, from Z’s TV series “Court 3”), her faster-living friend Stella (Eyrún Björk Jakobsdóttir) and Stella’s drug-dealing boyfriend Toni (Sigurbjartus Sturla Atlason) rob a man they have conned in an internet sex scam, the film grabs viewers and doesn’t let up for the next two hours. Obviously, it’s a scam that the two others have worked before, but for Magnea, it’s just the beginning. This pleasingly zaftig, innocent-looking, middle-class girl is bored with school and her longtime friends. She’s physically attracted to Stella and willing to try anything the older girl suggests.

Z and his co-screenwriter Birgir Örn Steinarsson aren’t particularly concerned with providing psychological explanations for Magnea’s behavior. We see that her parents are divorced and both her mother and father have new partners and younger children in their homes, but Magnea doesn’t seem unhappy moving from one place to the other. It makes it easier to do what she pleases. And what pleases Magnea most is to skip school and hang out with Stella.

With Stella, Magnea partakes of cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana and very soon, injectables. She loves the rush, but very quickly gets in over her head. In order to obtain money to pay for their habit, Magnea lets Stella post nude photos of her on a website to lure older, monied men with the promise of sex. Stella’s willingness to pimp out her friend in what they consider an easy game foreshadows a later, more serious act of disloyalty.

As a battered adult, Magnea is played by Lára Jóhanna Jónsdóttir (virtually unrecognizable from her role in the Sundance award-winner “And Breathe Normally”), struggling to turn tricks to earn enough for her next fix. In contrast, Stella (Kristín Thóra Haraldsdóttir) has been clean for a number of years and is working as a counselor in a women’s center. When the two finally meet again, their ultimate confrontation triggers a downbeat ending.

With his enthralling widescreen lensing, Johann Mani Johannsson (“Life in a Fishbowl”) brings a grungy lyricism to the early scenes of the film, finding visual matches for the characters’ exhilarating highs without in any way romanticizing them. And over the course of the film, his extreme closeups chart the devastation wrought on the once-healthy faces of the protagonists. Composer Olafur Arnalds (another “Fishbowl” collaborator) contributes an apt score, while Ulfur Teitur Traustason’s intelligent cutting builds up to a powerful showdown