Long article

www.nbcnews.com

www.nbcnews.com

In tax filings for 2020, Meya reported an annual salary of about $210,000 from his two nonprofit groups, according to tax disclosure documents. That kind of money bothers some in the Native American communities he’s worked in; on the Standing Rock reservation, the median income is just over $40,000.

Meya’s organizations have received more than $3.5 million in federal grants over the past 15 years for language revitalization projects with tribes across the country, records show. The Department of Health and Human Services alone has paid the Lakota Language Consortium nearly $1 million to create some of the textbooks the organization sells for $40 to $50 apiece

The Lakota Language Consortium had promised to preserve the tribe’s native language and had spent years gathering recordings of elders, including Taken Alive’s grandmother, to create a new, standardized Lakota dictionary and textbooks.

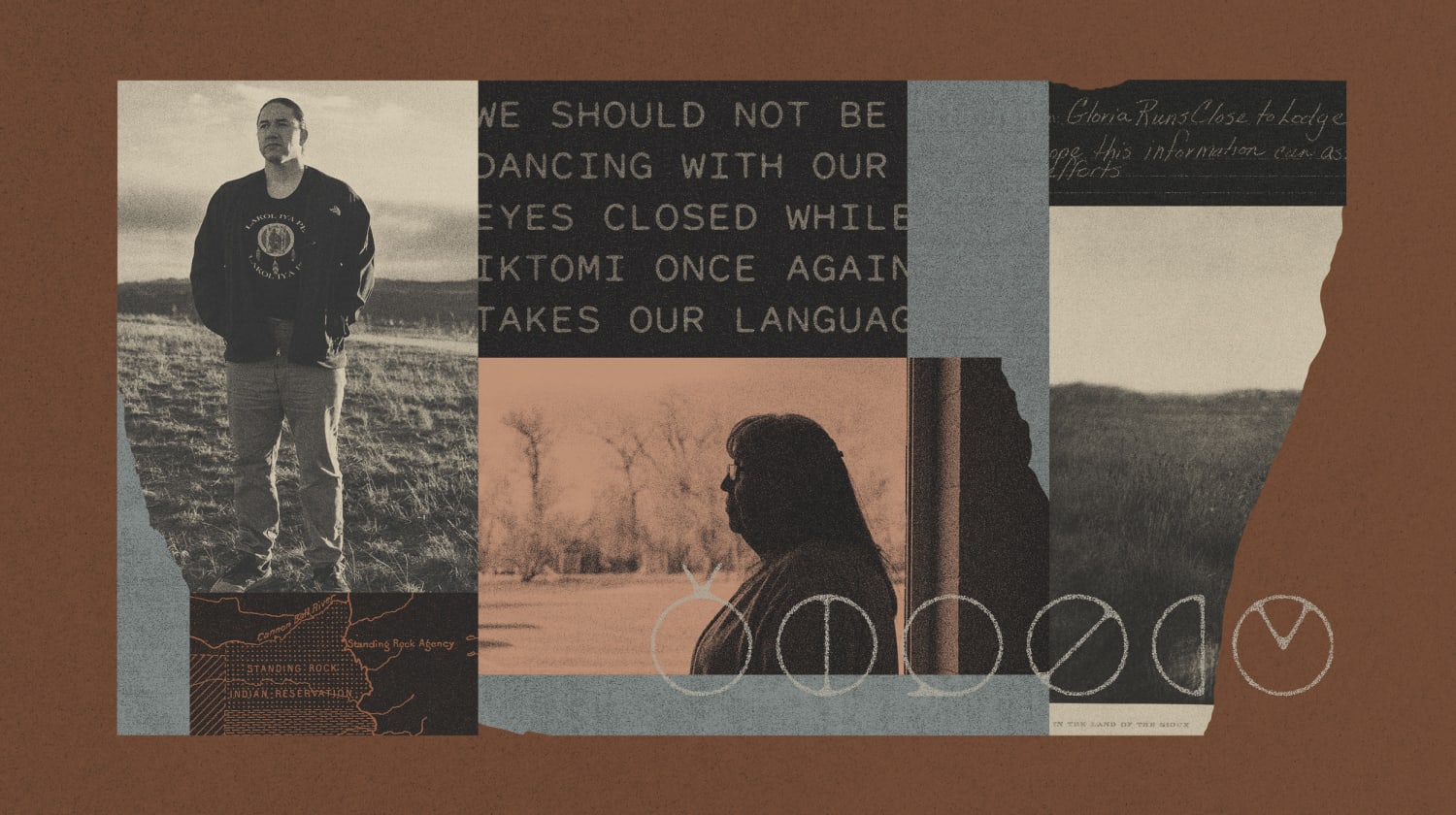

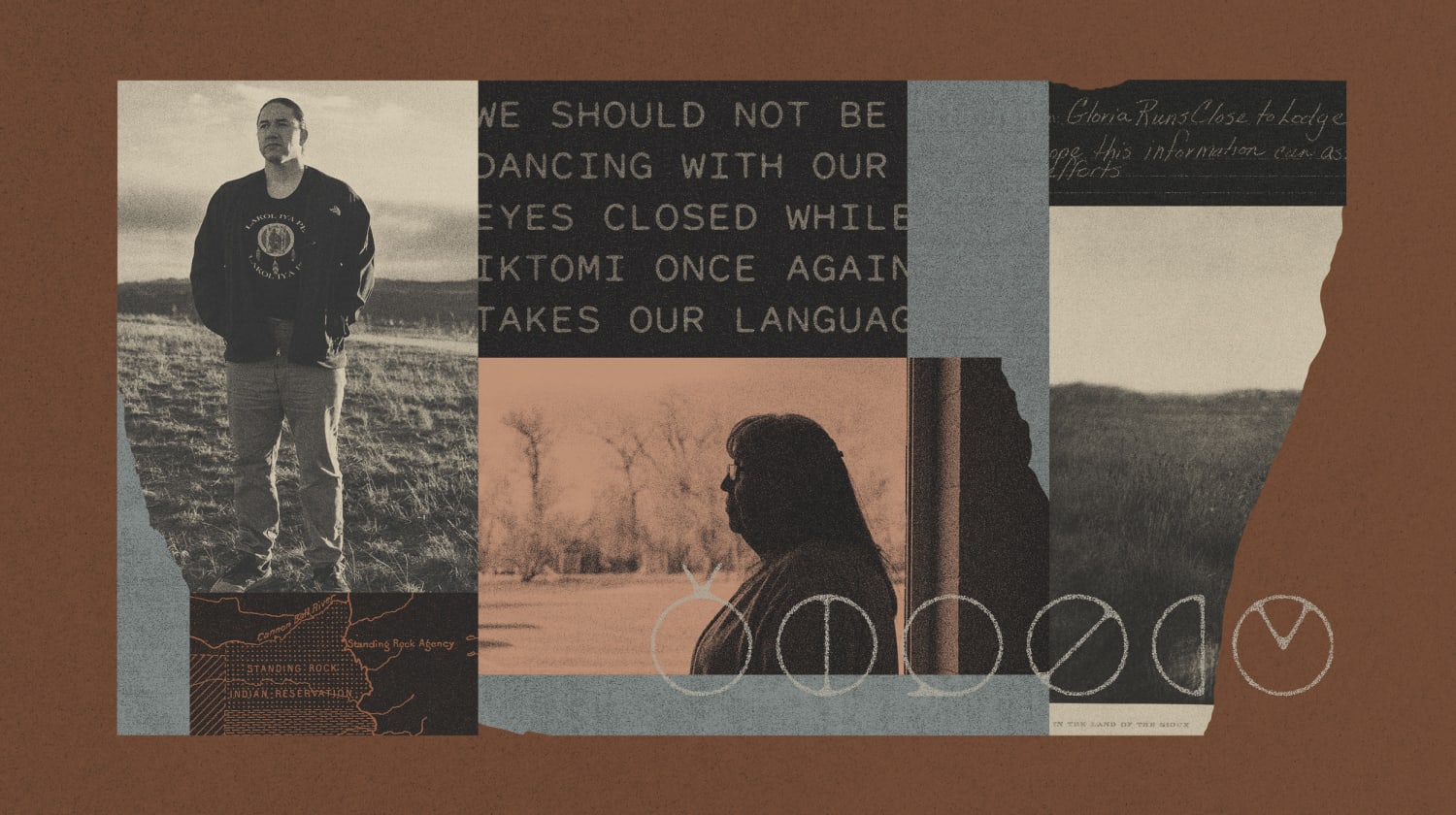

But when Taken Alive, 35, asked for copies, he was shocked to learn that the consortium, run by a white man, had copyrighted the language materials, which were based on generations of Lakota tradition. The traditional knowledge gathered from the tribe was now being sold back to it in the form of textbooks.

“No matter how it was collected, where it was collected, when it was collected, our language belongs to us. Our stories belong to us. Our songs belong to us,” Taken Alive, who teaches Lakota to elementary school students, told the tribal council in April.

On May 3, the tribal council voted nearly unanimously to banish the Lakota Language Consortium — along with its co-founder Wilhelm Meya and its head linguist, Jan Ullrich — from setting foot on the reservation. What the council took into consideration wasn’t just the organization’s dealings with the Standing Rock Sioux; it turned out at least three other tribes had also raised concerns about Meya, saying he broke agreements over how to use recordings, language materials and historical records, or used them without permission.

Meya denies this. A spokesman shared letters of support for Meya’s work from five tribes and tribal schools, though in recent interviews and statements to NBC News, officials with four of those tribes said they had concerns about Meya’s methods

Lakota elders helped a white man preserve their language. Then he tried to sell it back to them.

“No matter how it was collected, where it was collected, when it was collected, our language belongs to us," said Ray Taken Alive, a Lakota teacher.

In tax filings for 2020, Meya reported an annual salary of about $210,000 from his two nonprofit groups, according to tax disclosure documents. That kind of money bothers some in the Native American communities he’s worked in; on the Standing Rock reservation, the median income is just over $40,000.

Meya’s organizations have received more than $3.5 million in federal grants over the past 15 years for language revitalization projects with tribes across the country, records show. The Department of Health and Human Services alone has paid the Lakota Language Consortium nearly $1 million to create some of the textbooks the organization sells for $40 to $50 apiece

The Lakota Language Consortium had promised to preserve the tribe’s native language and had spent years gathering recordings of elders, including Taken Alive’s grandmother, to create a new, standardized Lakota dictionary and textbooks.

But when Taken Alive, 35, asked for copies, he was shocked to learn that the consortium, run by a white man, had copyrighted the language materials, which were based on generations of Lakota tradition. The traditional knowledge gathered from the tribe was now being sold back to it in the form of textbooks.

“No matter how it was collected, where it was collected, when it was collected, our language belongs to us. Our stories belong to us. Our songs belong to us,” Taken Alive, who teaches Lakota to elementary school students, told the tribal council in April.

On May 3, the tribal council voted nearly unanimously to banish the Lakota Language Consortium — along with its co-founder Wilhelm Meya and its head linguist, Jan Ullrich — from setting foot on the reservation. What the council took into consideration wasn’t just the organization’s dealings with the Standing Rock Sioux; it turned out at least three other tribes had also raised concerns about Meya, saying he broke agreements over how to use recordings, language materials and historical records, or used them without permission.

Meya denies this. A spokesman shared letters of support for Meya’s work from five tribes and tribal schools, though in recent interviews and statements to NBC News, officials with four of those tribes said they had concerns about Meya’s methods

still havent learned huh...

still havent learned huh...