ogc163

Superstar

Back in February, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Program for Public Discourse convened a forum on “Meritocracy in Higher Education.” The event was hosted by Sarah Treul, a political scientist at UNC, and featured the New York Times opinion columnist Ross Douthat, the anthropologist Caitlin Zaloom, the philosopher Anastasia Berg, and the writer Thomas Chatterton Williams, the latter three of whom had written about meritocracy for The Chronicle Review a few months earlier.

This discussion took place before Covid-19 changed everything. But the topics — the definition of meritocracy, the role of universities in a just society, the composition of socioeconomic class, and the real purpose of education — are as relevant as ever. As we figure out what to make of our university system in the wake of this unprecedented crisis, this conversation offers an urgent and intelligent guide.

Sarah Treul: When I think of the meritocratic ideal — that social and economic rewards, rather than family status, should track achievement — it’s very much in alignment with the American dream, working hard, and pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. But here, with the exception of Thomas, all of you seem to be against meritocracy, which is an increasingly popular opinion in American culture.

How did we get here?

Caitlin Zaloom: Meritocracy begins with the idea that people have to be measured on a scale of human value. So when we have decided that meritocracy is the way into higher education — or in particular into government, via higher education — it becomes an essential problem, because participation is then premised on the idea of achievement on a hierarchy of values which you may or may not have subscribed to in the first place.

Anastasia Berg: I don’t think I am against meritocracy. Obviously certain roles in society and certain honors should be going to someone who is most competent for them: the Nobel Prize, or a teaching award, or who should perform eye surgery on us.

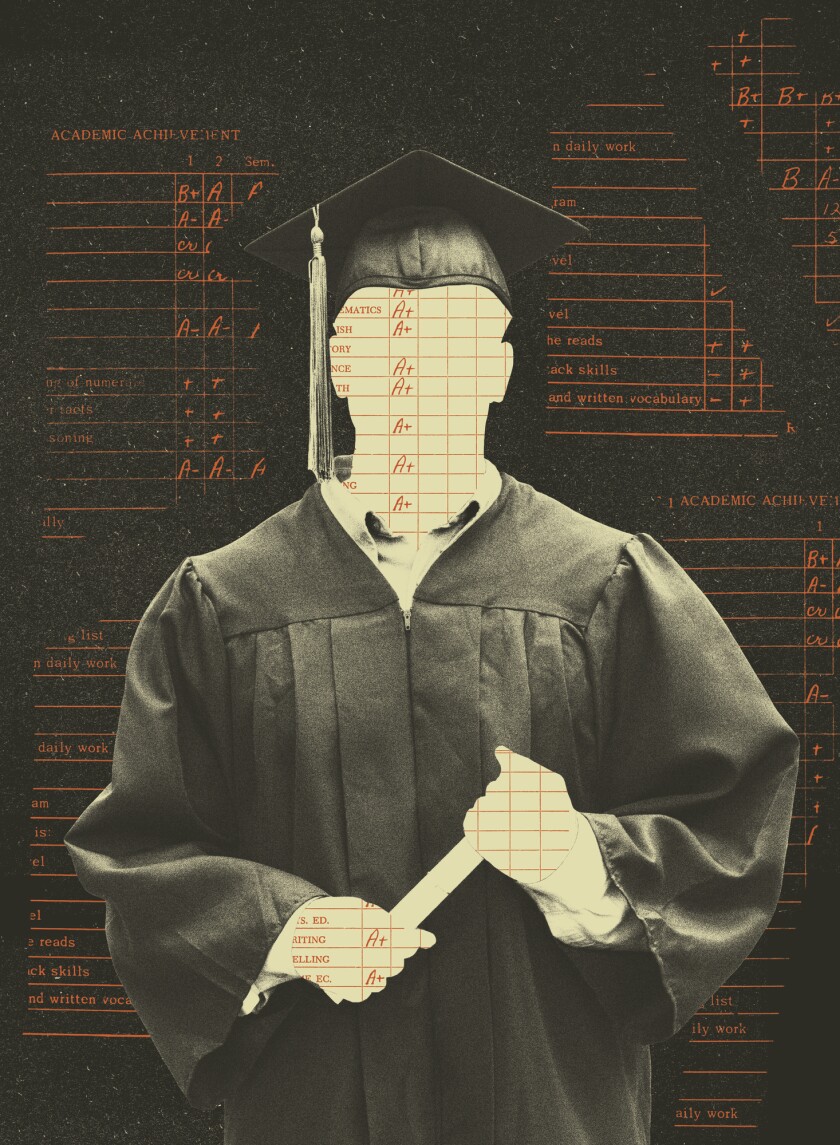

The question is whether this is the right measure for determining who should be entering universities. There are objections from the left and from the right. I find the left ones persuasive, which is to say, in effect, that the pretensions to meritocracy are not borne out, if we actually look at who gets into colleges. We find out that there’s huge correlation between the kind of material support that people have, and their ability to perform on the kind of exams that allow people to get into colleges.

But what I also find problematic has to do with what has formerly been thought of as a conservative critique, although I think that leftists and liberals and progressives should be as concerned about it as anyone else: The current way of running college admissions concentrates talent, ambition, and competence in very few areas — on the coasts, in a very few universities — and draws potential leaders from communities elsewhere. Moreover, the current system leaves people blind to all the ways in which they owe gratitude to a community, for all the help that allowed them to achieve.

Ross Douthat: It’s useful to remember that the term “meritocracy” was coined as a description of a dystopia, in a book by a British civil servant written in the late ’50s called The Rise of the Meritocracy. It was a tongue-in-cheek evocation of some pompous civil servant from somewhere around our own era, looking back on what he saw as the self-selection of the cognitive elite to rule over a society that was drained of talent, drained of ambition, and had all power centers outside the elite deprived of leadership and talent from within.

It’s reasonable to look at class divisions in the United States and much of the West and say that at least a partial version of that dystopia has come to pass. College-educated and more-than-college-educated Americans cluster together in geographic hubs in ways that they did not 50 or 60 years ago. With that concentration comes a mix of economic and cultural stratification that is linked to populist disturbances on the right and the left alike. You can trace similar geographies in Brexit, and support for the National Front in France, and so on.

There are two questions that hang over meritocratic debates. First, are there ways to successfully either devolve or claim from below forms of power in our society that aren’t dependent on credentialism? And second, is there a different kind of education that we could give to our meritocrats that might better equip them to govern the Western world slightly better than it’s been governed for the last 20 years or so?

Thomas Chatterton Williams: At the risk of being the most myopic analyst here, I want to talk about meritocracy not in the abstract but through the lens of personal experience. My father was a black man from the segregated South, really old enough to be my grandfather — he’s 82, born in 1937. He is the first in his family to get an education, and he did not grow up in a meritocracy. He grew up in an America that told him when he was pursuing his graduate education that ******s don’t get deferments in the state of Texas. So he was getting drafted when every white student was getting a deferment. That, in my book, is not a meritocracy.

Part of civic duty is feeling that you have something in common with someone who’s different from you.

But he raised my brother and me with a kind of immigrant’s belief in the idea that knowledge and effort and exertion are the only power of the poor and the oppressed. We attacked everything that was in our control. That really came down to the SAT test for me, because I didn’t even go to the kind of high school that offered AP courses. So my GPA wasn’t going to reflect the same type of effort as people who were going to prep schools. But there was a standardized measure that I could put all my effort into, and that was the SAT. To do well on the SAT also gave me confidence that I wasn’t getting a handout, that I could perform in spaces where other people had greater advantages than I had. I understand that that’s a selfish way of looking at the matter, but I’ve come to the conclusion that it takes a kind of privilege to sneer at meritocratic measures that allow people to advance.

Treul: Why has meritocracy as it relates to college admissions become such a lightning rod?

Zaloom: For families, getting into a prestigious college feels like the way that they can give their kid a shot. But lower-income people are largely shut out or discouraged from elite universities — that’s a background fact — and now, even for middle-class people, 50 percent of middle-class young adults can expect to do less well than their parents. We’re in this very unequal and unstable situation, even for middle-class people who these universities were designed to support.

Treul: How do we strengthen public education before college? I feel like we’re putting a lot on colleges.