(this album is really like a book for your mind, liberating our communities, and eating and living healthy...not to mention just about everything they spit about actually happened during bush and obama's presidencies) http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/interviews/lets-get-free-living-hip-hop

http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/interviews/lets-get-free-living-hip-hop

http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/interviews/lets-get-free-living-hip-hop

Let's Get Free: Living Hip-Hop History Fifteen Years Later

February 23, 2015 dead prez interviewed by Gabriel San Roman

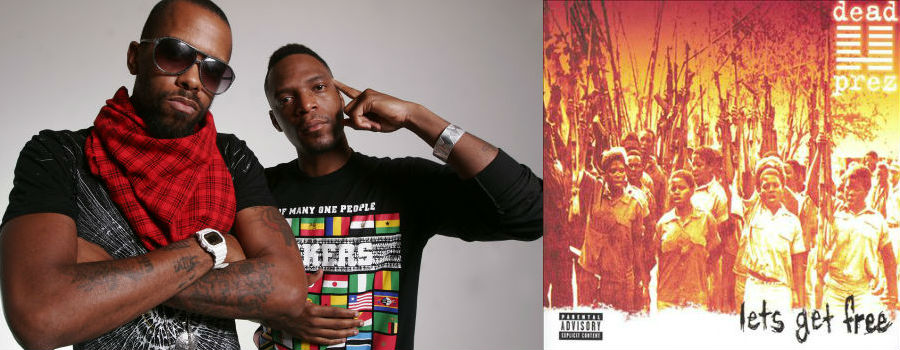

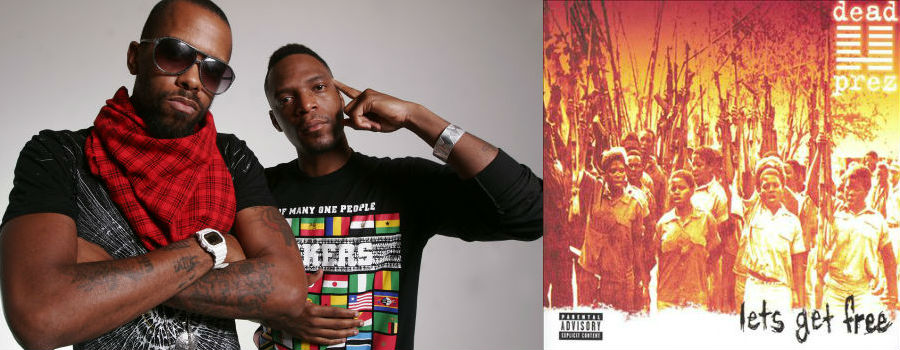

dead prez ( © Zubari, 2008), the cover art from Let's Get Free (Loud Records, 2000)

">

dead prez ( © Zubari, 2008), the cover art from Let's Get Free (Loud Records, 2000)

Rap duo dead prez exploded on the hip-hop scene 15 years ago like a Molotov cocktail. Their debut album Let’s Get Free, released March 14, 2000 on Loud Records, excoriated injustice with unabashed revolutionary bravado. Together M-1 and Stic.man revived the prophetic and political potential of hip-hop at a time when crass commercial rap further entrenched itself on the airwaves. Dreadlocked and militant, the MCs tackled mass incarceration, school indoctrination, and Black socialist liberation. They situated themselves as belonging on the spectrum “somewhere between N.W.A and P.E.” The 18-track effort seamlessly wove hints of jazz, poetry and the blues into its seditious beats.

Let’s Get Free bristled with a sense of urgency like on “Police State” where the lyrics decry, “And the people don't never get justice / And the women don't never get respected / And the problems don't never get solved / And the jobs don't never pay enough/ So the rent always be late / Can you relate? / We livin in a police state.” Masterfully mixing together speech excerpts between songs from Uhuru Movement founder Omali Yeshytela and historical voices of Black Panthers like Fred Hampton and Huey Newton, Let’s Get Free paced itself like an incendiary mixtape whose community ended up being a global one.

On February 10, dead prez performed Let’s Get Free as an album show for the first time ever at the Observatory in Santa Ana. The sold out crowd clamored as “Wolves,” a Yeshytela speech set to music played. In the greenroom, Stic.man sipped on herbal tea and did pushups. The duo readied themselves for the moment with a ritual pouring out water and voicing their offerings. They emerged from behind the curtain as “I’m a African” echoed through the walls of the venue. Fans faithfully recited the lyrics of every song as the duo powered through “They Schools,” “Propaganda,” and “Psychology,” before bringing things to a fervor with “Hip-Hop.”

The night cemented Let’s Get Free as all too resonate today to simply rest upon its well deserved mantle as a masterpiece of political rap. Before and after the show, I spoke with dead prez about the album and their recollections making it.

What was dead prez before Let’s Get Free?

M-1: I met Stic in 1990-1991 in Tallahassee, Florida. I attended Florida A&M University. We were young people trying to figure out the world, that’s all. We studied revolutionaries and thought we might want to be revolutionaries. That’s genuinely what created dead prez. It wasn’t contrived from a concept at all. It was actually the lives we were trying to live and figure out through our pursuit. A lot that, of course, was based off our political ideologies. I quickly passed through a stage of being a student on campus after two or three semesters. We ended up forming an organization called the Black Survival Movement. That movement led to us joining other political organizations. That journey is still happening. It’ll never stop. For me, music was a way to do what I couldn’t do with a leaflet in my neighborhood. That’s who we were before the actual name "dead prez." Before that, we were a group called The Masses Want War and actually we were The Heads From the Attic and then there were several MC crews in that big crew.

The back story behind the album also included taking a risk in moving to New York. What was that experience like?

Stic.man: We had a vision based on our love for Mobb Deep and Wu-Tang Clan at the time. They happened to be our biggest influences and inspirations. We lived in the South, in Florida. In order to get our voice heard with the type of music that we make, we needed to be in that environment. We were going to move to New York and attempt to sign to Loud Records or somewhere similar and have a better chance than the booty-club type of music in the South. A lot of our homies in our neighborhood and other talented artists, we got nine of us together and a little bit of money, maybe like $600, and we moved to New York. Of course, that ended super fast. The next thing you know, we were staying with my girlfriend’s sister and just had the luck of an electric fire in the wall that made it obvious that there was too many people in the apartment. That was our last day there. Over time it just got to the point where the money we had couldn’t add up and the subway began to be the overnight place to live. The year that we were there, I think in ’94, there was one of the worst blizzards. It was my first time seeing snow. We were literally knee deep. But we had our vision, our dream to stay and continue. Over time, we ran into Brand Nubian and Lord Jamar. We started working together and actually signed with the label we initially wanted to.

What are your thoughts looking back at 15 years of that album?

M-1: Let’s Get Free alone was like the contents page to a book that we wanted to write. It talked about what might be covered inside the book but it still had a lot to go. It was a statement that we wanted to make to the world that we thought we might not be able to make again, you know what I’m sayin. We wanted to able to say all we could while we could say it.

Stic.man: Let’s Get Free really was all of the demos and all the studio time in Florida, all the experiences in the political education and being members of the National Democratic Uhuru Movement. All the demos in Brooklyn and getting a demo that got us signed and then working on songs to see what the album would be like, all of those things became 20-plus years of our lives.

How resonate do the messages of the album remain today?

M-1: Politically for me, I think it was prophetic in a certain way. Since then we’ve been, in many different ways, touching on the same stuff that has primary contradiction in the things that produced the songs in Let’s Get Free. We’ve been able to understand that contradiction from the beginning. It hasn’t moved or changed. The same problems we had before is the same problems that we’re having now. What we have been trying to do for many years since Let’s Get Free is talk about it in different ways and not make the same ol’ song over again. I could, in fact, make the same song over again because they’re still relevant in that way. It has absolutely nothing to do with me or Stic in an egotistical way. We just study. We’re just social scientists. We study the world and figure out how to change it. Anybody who is trying to do that is going to make the same noises we making.

How did “Hip-Hop” come together in the studio? And is it true Kanye West co-produced it?

Stic.man: There’s a big myth that Kanye West produced our song “Hip-Hop.” That’s one of the biggest myths about that album. The raggedy bass, I actually produced that. Kanye West produced the remix. I was in the studio. We had most of the songs recorded already. We had the vision. We knew the direction the album was going. We were trying to make a well-rounded record, but we didn’t know what would be a single. I was at a place that we called Warrior Studios and I was working on the ASR-10, the old 16-bit sound. I remember when I was growing up in Florida the whole thing about music that drove us crazy was the bass and just seeing the woofers just vibrate. At that time, East Coast hip-hop, there was bass but it wasn’t like 2 Live Crew bass. In my mind, I was just looking to create a bass that rattled like back in the day. I started playing around with the wheels on the ASR-10 and I was literally making a joke when M1 and about six homies came into the studio. I had the basic drums and bass. “Whatchu workin’ on,” M1 said and I was like “Yo, check this out.” I made up “It’s Bigger Than Hip-Hop.” I didn’t really know what that meant. I just knew something was going to go on the hook. He just looked at me like “Dude, that’s crazy!” M1 started writing and then I ended up writing my verse. Then we played it for the label. Instantly, they all was like “that’s the single, that’s what we’ve been waiting for, let’s go.” That ended up being the lead single and to this day our biggest tune.

Chairman Omali Yeshytela’s speeches are peppered throughout Let’s Get Free as well as voices from Black Panther history giving the album a political mixtape feel. How did that come together?

M1: Well, like I said, it wasn’t contrived. It was actually the lives that we lived. We met the Uhuru Movement who gave us the majority, the brunt of our political education and our actual work, not just songs. We were part of many real campaigns that organized around this country. I only trained in that job as an MC because I think people can relate to the message that comes from this kind of music. That’s why I wouldn’t ever make any other kind of music. To me it would abandon what I came in it to do. For the way it sounded, we wanted to make a statement in a time when people weren’t making it anymore. The people who taught us, that’s what their job was. The KRS-Ones, the part of Big Daddy Kane, the part of Rakim that gave us what we are, you know what I’m sayin’. We knew we had to make that statement. That’s why it sounds like we learned from the Black Panther Party because we were definitely doing that and actually involved in Uhuru. It wasn’t like we stumbled across a Chairman Omali speech. I was there for that. I recorded that with my own microphone. I was organizing. I would take that and go right into the street. That’s why it’s in there and that’s why we’ll never make another Let’s Get Free, because that moment was that.

Where do you think the album is situated in hip-hop history?

Stic.man: Humbly speaking, based on the cycle of growing up in today’s world, there’s always going to be that age where we come into an awakening politically. When we was growing up, Rodney King was the situation that was a national outrage. When the Panthers was growing up it was people like Emmett Till. Each generation, there’s been conditions that influences the consciousness of those times and the music documents that. We didn’t set out to do that, but what we realize is that Let’s Get Free marked that process of people coming into the realization that our condition needs to change. That’s going to constantly happen as long as there’s oppression. The album has had this much longevity because there’s people constantly turning 13 and there’s constant evidence of the Reagan, Bush or slavery era. It became a soundtrack to waking up and inspiring consciousness, resistance and change along the line for some people as reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X. We’re just part of our history. That’s what the album captured.

How was it performing Let’s Get Free as a live show for the first time?

Stic.man: I’m just grateful to be a part of the experience and to have the opportunity to take something we would do for fun, for free, that was just our own therapy, our own realization process. To be able to share with our community, with the world, fifteen years later to a sold-out crowd in a city I’ve never been, you know what I’m sayin, for some people that probably wasn’t 2 or 3 years old when that record dropped. Man, it’s a grateful feeling. It’s also a bittersweet kind of thing to know that all of those issues are just as relevant now as opposed to we’ve gotten much closer to being like “Remember that, back in the day when people were oppressing each other? Remember when we solved that?” I’m grateful as a musician to have made some relevant music that can inspire people and give a voice to a marginalized condition. I wish our album was obsolete. Unfortunately, it’s still relevant in the present.

So what’s in the future for dead prez after the 15th anniversary of its debut?

M1: Who knows? We still here. Hopefully the revolution. That’s what it’s all for. We gotta win! Today, I’ve grown. It’s not static. I’m not dogmatic. I look for new approaches as to what we understand as our liberation and I’m open to that. But, what I do realize scientifically is that this is always going to be imperialism, we’re always going to be in the stages of imperialism and people have given us a great wealth of information about what that is. People like Frantz Fanon, Patrice Lumumba and Omali Yeshytela. They’re great revolutionary theorists. Revolution is good for us. It’s not a fringe or extremist thing.

dead prez is a revolutionary hip-hop duo based in New York City. The group's albums include Information Age, Revolutionary But Gangsta and Let's Get Free, which features the well-known track "It's Bigger Than Hip-Hop."

Gabriel San Román is the author of Venceremos: Victor Jara and the New Chilean Song Movement, co-creator of the 2015 Calendar of Revolt and a writer with OC Weekly.

http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/interviews/lets-get-free-living-hip-hop

http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/interviews/lets-get-free-living-hip-hop

Let's Get Free: Living Hip-Hop History Fifteen Years Later

February 23, 2015 dead prez interviewed by Gabriel San Roman

dead prez ( © Zubari, 2008), the cover art from Let's Get Free (Loud Records, 2000)

">

dead prez ( © Zubari, 2008), the cover art from Let's Get Free (Loud Records, 2000)

Rap duo dead prez exploded on the hip-hop scene 15 years ago like a Molotov cocktail. Their debut album Let’s Get Free, released March 14, 2000 on Loud Records, excoriated injustice with unabashed revolutionary bravado. Together M-1 and Stic.man revived the prophetic and political potential of hip-hop at a time when crass commercial rap further entrenched itself on the airwaves. Dreadlocked and militant, the MCs tackled mass incarceration, school indoctrination, and Black socialist liberation. They situated themselves as belonging on the spectrum “somewhere between N.W.A and P.E.” The 18-track effort seamlessly wove hints of jazz, poetry and the blues into its seditious beats.

Let’s Get Free bristled with a sense of urgency like on “Police State” where the lyrics decry, “And the people don't never get justice / And the women don't never get respected / And the problems don't never get solved / And the jobs don't never pay enough/ So the rent always be late / Can you relate? / We livin in a police state.” Masterfully mixing together speech excerpts between songs from Uhuru Movement founder Omali Yeshytela and historical voices of Black Panthers like Fred Hampton and Huey Newton, Let’s Get Free paced itself like an incendiary mixtape whose community ended up being a global one.

On February 10, dead prez performed Let’s Get Free as an album show for the first time ever at the Observatory in Santa Ana. The sold out crowd clamored as “Wolves,” a Yeshytela speech set to music played. In the greenroom, Stic.man sipped on herbal tea and did pushups. The duo readied themselves for the moment with a ritual pouring out water and voicing their offerings. They emerged from behind the curtain as “I’m a African” echoed through the walls of the venue. Fans faithfully recited the lyrics of every song as the duo powered through “They Schools,” “Propaganda,” and “Psychology,” before bringing things to a fervor with “Hip-Hop.”

The night cemented Let’s Get Free as all too resonate today to simply rest upon its well deserved mantle as a masterpiece of political rap. Before and after the show, I spoke with dead prez about the album and their recollections making it.

What was dead prez before Let’s Get Free?

M-1: I met Stic in 1990-1991 in Tallahassee, Florida. I attended Florida A&M University. We were young people trying to figure out the world, that’s all. We studied revolutionaries and thought we might want to be revolutionaries. That’s genuinely what created dead prez. It wasn’t contrived from a concept at all. It was actually the lives we were trying to live and figure out through our pursuit. A lot that, of course, was based off our political ideologies. I quickly passed through a stage of being a student on campus after two or three semesters. We ended up forming an organization called the Black Survival Movement. That movement led to us joining other political organizations. That journey is still happening. It’ll never stop. For me, music was a way to do what I couldn’t do with a leaflet in my neighborhood. That’s who we were before the actual name "dead prez." Before that, we were a group called The Masses Want War and actually we were The Heads From the Attic and then there were several MC crews in that big crew.

The back story behind the album also included taking a risk in moving to New York. What was that experience like?

Stic.man: We had a vision based on our love for Mobb Deep and Wu-Tang Clan at the time. They happened to be our biggest influences and inspirations. We lived in the South, in Florida. In order to get our voice heard with the type of music that we make, we needed to be in that environment. We were going to move to New York and attempt to sign to Loud Records or somewhere similar and have a better chance than the booty-club type of music in the South. A lot of our homies in our neighborhood and other talented artists, we got nine of us together and a little bit of money, maybe like $600, and we moved to New York. Of course, that ended super fast. The next thing you know, we were staying with my girlfriend’s sister and just had the luck of an electric fire in the wall that made it obvious that there was too many people in the apartment. That was our last day there. Over time it just got to the point where the money we had couldn’t add up and the subway began to be the overnight place to live. The year that we were there, I think in ’94, there was one of the worst blizzards. It was my first time seeing snow. We were literally knee deep. But we had our vision, our dream to stay and continue. Over time, we ran into Brand Nubian and Lord Jamar. We started working together and actually signed with the label we initially wanted to.

What are your thoughts looking back at 15 years of that album?

M-1: Let’s Get Free alone was like the contents page to a book that we wanted to write. It talked about what might be covered inside the book but it still had a lot to go. It was a statement that we wanted to make to the world that we thought we might not be able to make again, you know what I’m sayin. We wanted to able to say all we could while we could say it.

Stic.man: Let’s Get Free really was all of the demos and all the studio time in Florida, all the experiences in the political education and being members of the National Democratic Uhuru Movement. All the demos in Brooklyn and getting a demo that got us signed and then working on songs to see what the album would be like, all of those things became 20-plus years of our lives.

How resonate do the messages of the album remain today?

M-1: Politically for me, I think it was prophetic in a certain way. Since then we’ve been, in many different ways, touching on the same stuff that has primary contradiction in the things that produced the songs in Let’s Get Free. We’ve been able to understand that contradiction from the beginning. It hasn’t moved or changed. The same problems we had before is the same problems that we’re having now. What we have been trying to do for many years since Let’s Get Free is talk about it in different ways and not make the same ol’ song over again. I could, in fact, make the same song over again because they’re still relevant in that way. It has absolutely nothing to do with me or Stic in an egotistical way. We just study. We’re just social scientists. We study the world and figure out how to change it. Anybody who is trying to do that is going to make the same noises we making.

How did “Hip-Hop” come together in the studio? And is it true Kanye West co-produced it?

Stic.man: There’s a big myth that Kanye West produced our song “Hip-Hop.” That’s one of the biggest myths about that album. The raggedy bass, I actually produced that. Kanye West produced the remix. I was in the studio. We had most of the songs recorded already. We had the vision. We knew the direction the album was going. We were trying to make a well-rounded record, but we didn’t know what would be a single. I was at a place that we called Warrior Studios and I was working on the ASR-10, the old 16-bit sound. I remember when I was growing up in Florida the whole thing about music that drove us crazy was the bass and just seeing the woofers just vibrate. At that time, East Coast hip-hop, there was bass but it wasn’t like 2 Live Crew bass. In my mind, I was just looking to create a bass that rattled like back in the day. I started playing around with the wheels on the ASR-10 and I was literally making a joke when M1 and about six homies came into the studio. I had the basic drums and bass. “Whatchu workin’ on,” M1 said and I was like “Yo, check this out.” I made up “It’s Bigger Than Hip-Hop.” I didn’t really know what that meant. I just knew something was going to go on the hook. He just looked at me like “Dude, that’s crazy!” M1 started writing and then I ended up writing my verse. Then we played it for the label. Instantly, they all was like “that’s the single, that’s what we’ve been waiting for, let’s go.” That ended up being the lead single and to this day our biggest tune.

Chairman Omali Yeshytela’s speeches are peppered throughout Let’s Get Free as well as voices from Black Panther history giving the album a political mixtape feel. How did that come together?

M1: Well, like I said, it wasn’t contrived. It was actually the lives that we lived. We met the Uhuru Movement who gave us the majority, the brunt of our political education and our actual work, not just songs. We were part of many real campaigns that organized around this country. I only trained in that job as an MC because I think people can relate to the message that comes from this kind of music. That’s why I wouldn’t ever make any other kind of music. To me it would abandon what I came in it to do. For the way it sounded, we wanted to make a statement in a time when people weren’t making it anymore. The people who taught us, that’s what their job was. The KRS-Ones, the part of Big Daddy Kane, the part of Rakim that gave us what we are, you know what I’m sayin’. We knew we had to make that statement. That’s why it sounds like we learned from the Black Panther Party because we were definitely doing that and actually involved in Uhuru. It wasn’t like we stumbled across a Chairman Omali speech. I was there for that. I recorded that with my own microphone. I was organizing. I would take that and go right into the street. That’s why it’s in there and that’s why we’ll never make another Let’s Get Free, because that moment was that.

Where do you think the album is situated in hip-hop history?

Stic.man: Humbly speaking, based on the cycle of growing up in today’s world, there’s always going to be that age where we come into an awakening politically. When we was growing up, Rodney King was the situation that was a national outrage. When the Panthers was growing up it was people like Emmett Till. Each generation, there’s been conditions that influences the consciousness of those times and the music documents that. We didn’t set out to do that, but what we realize is that Let’s Get Free marked that process of people coming into the realization that our condition needs to change. That’s going to constantly happen as long as there’s oppression. The album has had this much longevity because there’s people constantly turning 13 and there’s constant evidence of the Reagan, Bush or slavery era. It became a soundtrack to waking up and inspiring consciousness, resistance and change along the line for some people as reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X. We’re just part of our history. That’s what the album captured.

How was it performing Let’s Get Free as a live show for the first time?

Stic.man: I’m just grateful to be a part of the experience and to have the opportunity to take something we would do for fun, for free, that was just our own therapy, our own realization process. To be able to share with our community, with the world, fifteen years later to a sold-out crowd in a city I’ve never been, you know what I’m sayin, for some people that probably wasn’t 2 or 3 years old when that record dropped. Man, it’s a grateful feeling. It’s also a bittersweet kind of thing to know that all of those issues are just as relevant now as opposed to we’ve gotten much closer to being like “Remember that, back in the day when people were oppressing each other? Remember when we solved that?” I’m grateful as a musician to have made some relevant music that can inspire people and give a voice to a marginalized condition. I wish our album was obsolete. Unfortunately, it’s still relevant in the present.

So what’s in the future for dead prez after the 15th anniversary of its debut?

M1: Who knows? We still here. Hopefully the revolution. That’s what it’s all for. We gotta win! Today, I’ve grown. It’s not static. I’m not dogmatic. I look for new approaches as to what we understand as our liberation and I’m open to that. But, what I do realize scientifically is that this is always going to be imperialism, we’re always going to be in the stages of imperialism and people have given us a great wealth of information about what that is. People like Frantz Fanon, Patrice Lumumba and Omali Yeshytela. They’re great revolutionary theorists. Revolution is good for us. It’s not a fringe or extremist thing.

dead prez is a revolutionary hip-hop duo based in New York City. The group's albums include Information Age, Revolutionary But Gangsta and Let's Get Free, which features the well-known track "It's Bigger Than Hip-Hop."

Gabriel San Román is the author of Venceremos: Victor Jara and the New Chilean Song Movement, co-creator of the 2015 Calendar of Revolt and a writer with OC Weekly.

Get it done....I was on that shyt..........

Get it done....I was on that shyt..........