get these nets

Veteran

=============================

How Does Charleston Grapple With Its History? By Talking About It.

As the city's International African American Museum prepares for its late 2022 debut, Charlestonians speak up.

Mar 18, 2022

Until we reckon with history, we’re not going to be free,” Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, has said, comparing historical discourse in America unfavorably to that of countries like Germany, South Africa, and Rwanda, which have had their reckonings. “I think there’s something better waiting for us that we can’t get to until we talk honestly about our past.”

In 2018 Charleston, routinely voted the number one city in America, did an uncommon thing: It tried to go there, as it were. (This in a country that has seen a recent push to ban Toni Morrison’s Beloved because its depiction of slavery makes some readers uncomfortable.) Charleston’s legislature passed a resolution “recognizing, denouncing, and apologizing on behalf of the city of Charleston for the city’s role in regulating, supporting, and fostering slavery and the resulting atrocities inflicted by the institution.” It committed, as well, to pursuing “initiatives that honor the contributions of those who were enslaved” and to “ameliorating remaining vestiges of slavery.”

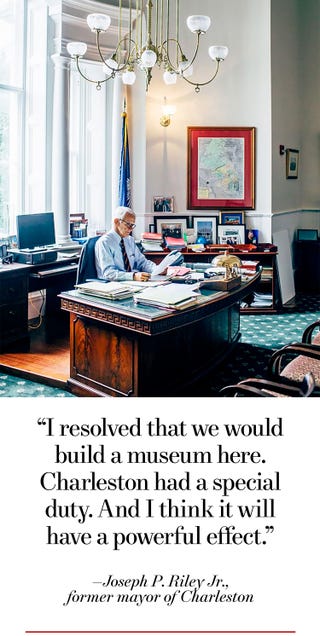

I’ve come to Charleston—my fourth visit in five years—for two reasons. First, to talk to Charlestonians about where things stand three years after the city’s apology. On my calendar are meetings with museum directors, historians, preservationists, artists, poets, guides, the pastor of a storied Black church, and the city’s popular 10-term former mayor, Joseph P. Riley Jr.

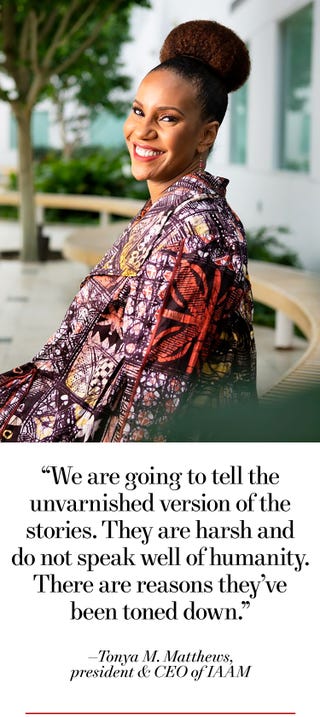

I’m here, too, in anticipation of a major step in the city’s promise to honor the contributions of the enslaved: Charleston’s long-awaited International African American Museum (IAAM). Its exterior is complete, its opening is now scheduled for late 2022, and it is the talk of the town, its mission being to “honor the untold stories of the African American journey at one of our country’s most sacred sites.”

A rendering of the International African American Museum, which will trace the tragedies and triumphs of the African diaspora.

The site in question is the southern bit of Gadsden’s Wharf. It was built in the 1770s by merchant and slaveholder Christopher Gadsden on the east side of the peninsula, along the Cooper River where it flows into the harbor and the Atlantic beyond. Here captive Africans were disgorged from slave ships. As many as 200 ships arrived in just the last 22 months of international trading, which ended in 1808, the merchants racing against the clock to maximize profits. “This is literally ground zero of American slavery,” says Tonya M. Matthews, IAAM’s president and CEO.

The forcefulness of Charleston’s 2018 resolution suggested that Charleston had a lot to apologize for. A brief primer: The city had been nothing less than the juggernaut of American slavery. Beginning in 1670, more enslaved Africans (the ones who survived the horrors of the Middle Passage) first set foot on land in Charleston than anywhere else in North America—some 200,000, nearly half of all who arrived during the two-and-a-half centuries of the international slave trade. The city had a relentless appetite for “new Negroes,” as imports from West Africa were called. The backbreaking, high mortality work on rice plantations required a constant infusion of fresh enslaved labor. (By 1860, Blacks comprised 60 percent of Charleston’s population.)

The interstate slave trade, supplying enslaved people to the cotton and sugar plantations of the Deep South, was just as lucrative, and it persisted until emancipation, in 1863. The immense wealth generated by rice (“Carolina gold” was in great demand throughout the Americas and Europe), together with the slave trade, created the billionaire class of the day. (It is their mansions we tour.) By the late 18th century the region was among the richest not only in North America but in the world. No wonder South Carolina statesmen led the opposition to the 19th-century abolition movements and that Charleston became a hotbed of secession, culminating in the firing on the Union garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor—the start of the Civil War.

The grand houses near Charleston’s Battery Park look out toward Fort Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired.

How do you honor the contributions of the enslaved, whose humanity was denied and largely undocumented? In Charleston, by looking around. “There is hardly an artifact here—antiques, silver, ordinary objects—that wasn’t crafted, maintained, handled in some way by enslaved people,” says Carl Borick, director of the Charleston Museum, showing me its galleries. “It fascinates me,” he continues, “that the white elite here relied on the enslaved workforce to do pretty much everything. The churches, houses, grand public buildings? We wouldn’t have any of that without the work of enslaved and free Blacks. The ironworkers were also Black, and they were producing much of what is the beauty and grandeur of this city. We are always looking for ways to better highlight that.”