“That’s where you find really cool stuff, in museums,” says Grohé. For about three weeks, Grohé worked in the museum’s basement, analyzing the hundreds of Omo carnivore fossils. “I was not just looking at otters,” she says. “I was looking at overall diversity [and] checking if the specimens we had in the database also matched the specimens we had in the drawers.”

Eventually, she came across a “weird” femur, the same one paleontologists uncovered back in the 70s. In a previous

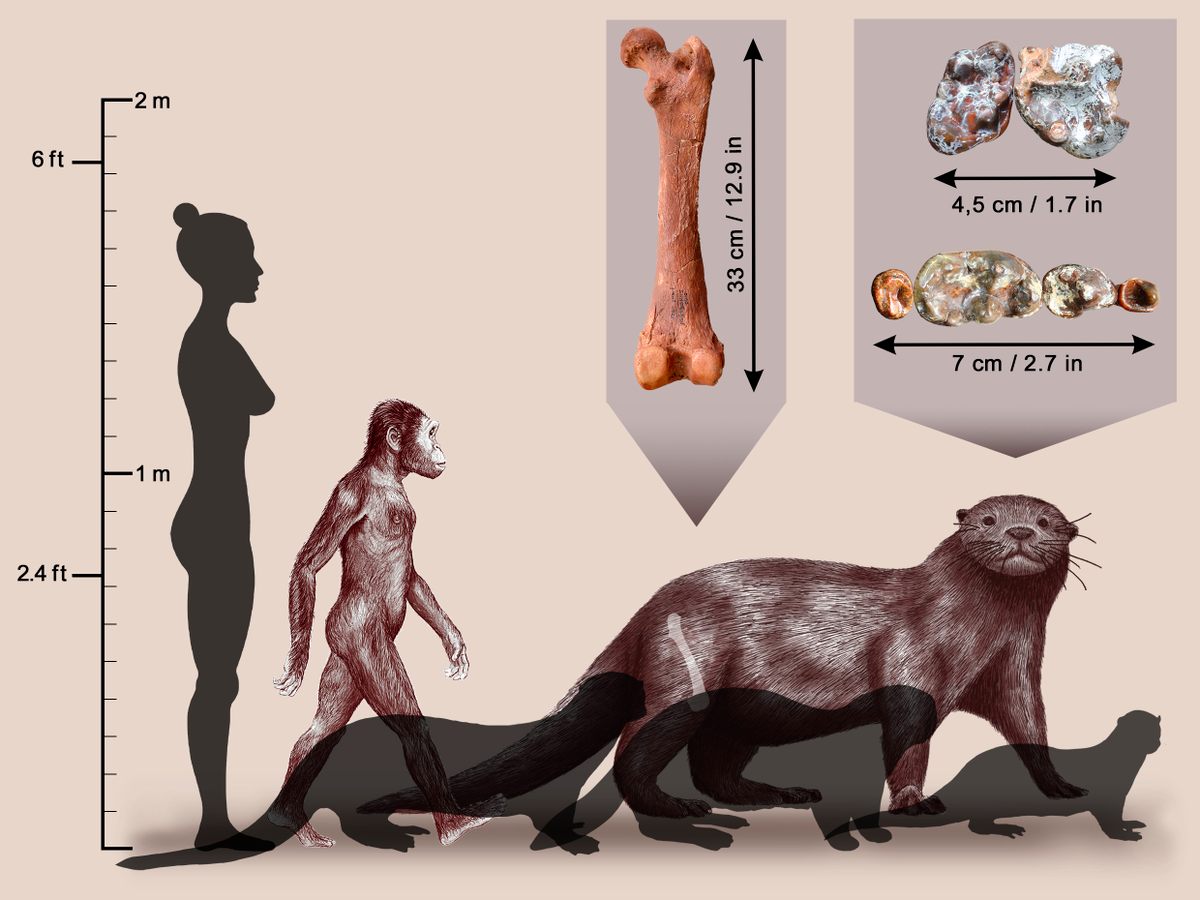

study, Lewis had identified that the femur came from a very big prehistoric otter. But that wasn’t the only thing that made this femur a little weird. “It was really, really long and that didn’t really match an aquatic mammal,” which have generally shorter femurs to help the animals swim. Grohé picked out a few other fossils—some teeth and bits of the cranium—that also didn’t seem to match any known species of otter.

The prehistoric giant otter weighed almost five times as much as

Australopithecus afarensis, the hominin species that “Lucy” belonged to. © Sabine Riffaut, Camille Grohé / Palevoprim / CNRS – Université de Poitiers

In July 2019, Grohé returned to Ethiopia, and this time went to the Lower Omo Valley to see where the fossils had been uncovered. “It’s a long ways,” says Kevin Uno of Columbia University, another author on the study. “Imagine driving across the state of Utah without a single paved road.” With 10 cars filled with paleontologists and supplies, it takes four days to reach the Omo from Addis Ababa. Nestled along the chai-colored river, the arid valley is dotted with stunning hills. “It looks like the Badlands in South Dakota,” says Uno.

While the paleontologists looked for fossilized carnivores, armed security personnel kept their eyes peeled for their living brethren. Lions stalk the grasses; crocodiles prowl the river. One morning in 2014, Uno remembers seeing the footprint of a lion stamped into the team’s fresh tire tracks.

Luckily, Grohé avoided any run-ins with living carnivores in 2019. Instead, she found some fossilized giant oysters. Guessing that

Enhydriodon omoensis was semi-aquatic, “I thought that could be a good meal for this otter,” she says. But when she analyzed some of the otter’s teeth back at her lab, she found something astounding.

Collaborating with Uno, Grohé and a team of scientists extracted small amounts of enamel from the

Enhydriodon omoensis’s teeth, which they

tested for carbon and oxygen isotopes. Grohé was surprised to find that the isotopes were from largely terrestrial sources. “It was feeding on a wide range of [land-based] prey,” says Grohé; the patterns were similar to those found in big cats and hyenas today. But whether the otter was hunting or scavenging, Grohé isn’t sure.

Almost 500 miles long, the Omo River winds through southwestern Ethiopia.

Rod Waddington/CC BY-SA 2.0

Enhydriodon omoensis wasn’t the only giant otter in Africa during the Pliocene and late Miocene, roughly seven million to two million years ago, but it was one of the last. “I expected it to have a very narrow range of habitat that could potentially explain why it went extinct,” says Grohé. Given that the otter had a large habitat and could eat just about anything, “I know less now why she went extinct.”

Lewis takes that question a step further—if a generalist like

Enhydriodon omoensis didn’t make the evolutionary cut, how did our human ancestors manage to survive? “It’s scary enough if you just think about surviving with lions and hyenas and leopards and all the living stuff,” but when you add in three species of saber-toothed cats, these giant otters, and all the other terrifying things of the Pliocene, “it’s amazing that [our hominin ancestors] came through this,” she says.

Grohé isn’t sure exactly what would’ve happened in an encounter between our early ancestors and

Enhydriodon omoensis. “I don’t know if it would’ve been necessarily aggressive towards you,” says Grohé. But nonetheless, she says, “I think, like [with] a bear, you don’t approach it.” Uno agrees, joking, “If I were to encounter this otter, I would have wanted our encounter to be at a distance.”