In California’s largest race bias cases, Latino workers are accused of abusing Black colleagues

In the last decade, the two largest race discrimination cases brought by the federal government in the Golden State alleged widespread abuse of hundreds of Black employees at Inland Empire warehouses.

In California’s largest race bias cases, Latino workers are accused of abusing Black colleagues

Margot RooseveltAug. 22, 2022 6 AM PT

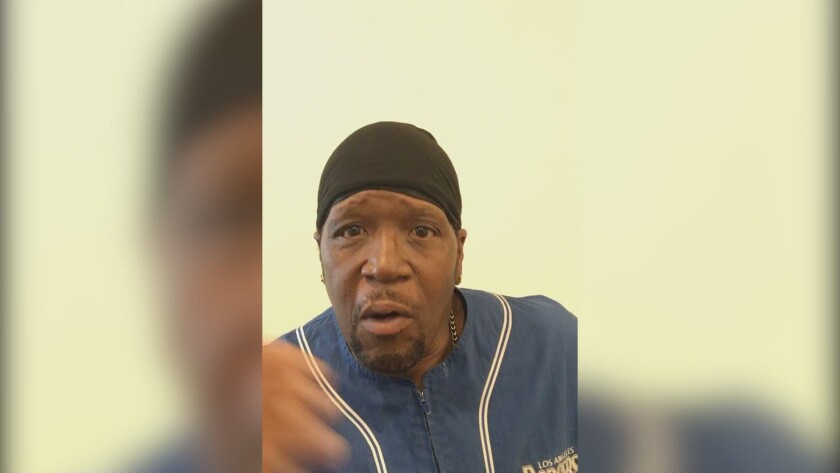

Leon Simmons is among hundreds of Black workers who say they faced racial harassment at Inland Empire warehouses.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

Nearly every day, the onetime Ontario warehouse employee said, he was stunned to hear racist slurs from Latino co-workers.

“They said it in English — they said it in Spanish all the time,” recalled Leon Simmons, a Black father of four with a deep voice and gentle manner. “When they look you right in the eye and call you the N-word to your face, that’s dehumanizing.”

Thirty-two miles away at a Moreno Valley warehouse, it was the same story. Another Black laborer, Benjamin Watkins, described how a Latina co-worker called to him: “‘Hey, monkey! Yeah, you!’ and waved a banana in her hand. A group of women burst out laughing.”

In America’s long history, harassment and discrimination against Black workers has usually involved white perpetrators — and that remains the case today. But with the rapid growth of the Latino population, now at 19% in the U.S. and 39% in California, Latinos form the majority in many low-wage workplaces. And instances of anti-Black bias and colorism among them is drawing new scrutiny, even as activists in the two communities forge alliances over criminal justice and economic development.

Latinos certainly are targets of job discrimination as well and continue to struggle for equity in the workplace. But the two largest racial bias cases brought by the federal government in California in the last decade alleged widespread abuse of hundreds of Black employees at warehouses in the Inland Empire, the state’s booming distribution hub for trade between the U.S. and Asia.

In interviews, Black employees said a torrent of racist insults and discriminatory treatment was mainly inflicted by Latino co-workers and supervisors who composed roughly three-quarters of the workforces at the sprawling facilities in Ontario and Moreno Valley.

“Mayate,” a type of beetle and Spanish slang for the N-word, was a common taunt, according to interviews and court filings.

Black employees will be compensated as a result of EEOC settlements with Cardinal Health, Ryder Integrated Logistics and Kimco Staffing Services over workplace discrimination.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission lawsuits alleged that supervisors at the global medical supplier Cardinal Health and at Ryder Integrated Logistics, a subsidiary of the trucking giant — along with their staffing firms — routinely ignored harassment in Spanish and English at their Inland Empire warehouses. They gave Black employees the hardest manual jobs, denied them training and promotions and failed to take action despite dozens of complaints, according to court filings and interviews.

Many of the Black workers were hired through temp agencies. When they complained, managers — both white and Latino — retaliated by disciplining them or abruptly firing them, according to the EEOC. Others felt forced to quit because of “intolerable working conditions created by the hostile work environment,” the lawsuits alleged.

Cardinal, Ryder and their temp firms denied the accusations. But as scores of Black employees came forward and the EEOC interviewed witnesses, the companies settled the cases last year rather than face jury trials.

“We are seeing an increase in larger race harassment cases,” said Anna Park, regional attorney for the EEOC’s Los Angeles district office. “The nature of them has gotten uglier. There’s a more blatant display of hatred with the N-word, with imagery, with nooses. All the violence you’re seeing in the news, it is manifesting in the employment context.”

In a state as diverse as California, offenders span all races and ethnicities, she said.

“Two decades ago discrimination was viewed as a Black-white paradigm,” Park said. “The feeling was minorities can’t be discriminating. But it could be Asians discriminating, it could be Latinos discriminating. Regardless of what color you are, you don’t get a free pass.”

Now about 300 Black workers are gaining compensation, some as much as tens of thousands of dollars, through the Inland Empire settlements. Cardinal agreed to pay $1.45 million. Ryder and Kimco Staffing Services, which supplied workers to Ryder, settled for $1 million each.

The warehouse operators and their staffing firms — including a Glendale temp agency, AppleOne, which supplied workers to Cardinal — must offer extensive harassment training in English and Spanish and submit to stringent monitoring for verbal abuse, bias and retaliation.

The Los Angeles Times contacted more than two dozen current and former Latino workers from Cardinal and Ryder. None agreed to an interview.

Nationwide, EEOC records show prejudice can afflict any race or ethnicity, but Black victims predominate.

Over the last decade, the agency has won settlements in 171 race discrimination suits involving Black workers, 59 cases involving Latino victims, 12 involving Asian victims and six involving white victims.

Though the agency tracks the race and ethnicity of victims, it does not compile official statistics on offenders. Nor are there databases of private cases categorized by perpetrators’ race. This makes it hard to gauge the extent of anti-Black hostility from Latino workers.

But court filings, victims’ allegations and employer records show that in the last decade, about a third of anti-Black bias suits filed by the EEOC’s Los Angeles and San Francisco offices involved discrimination by Latinos, about a third involved white offenders and a third were unspecific.

The suit against Cardinal Health and AppleOne was graphic.

Since at least 2016, the EEOC alleged, Black workers were subjected to the N-word by co-workers and managers “many times per day…including ‘n— bytch’, ‘lazy ass n— ain’t did no work all day,’ and ‘Look at those n—looking like monkeys, working like slaves like they should be.’”

The first worker to file a complaint described being called anti-Black slurs in English and Spanish, facing prejudice from a Latina supervisor and being deliberately run over with a cart by a Latino co-worker.

Photos taken by Black workers showed a women’s restroom defaced with graffiti: “N— stink up the aisles” and “Black pipo stink.” A men’s restroom was defaced with “n—killer.”

In a court filing, Cardinal acknowledged “derogatory graffiti,” but said it was promptly removed. A spokesman declined to address other worker allegations, citing the EEOC’s post-settlement statement: “Cardinal Health and AppleOne have put in place measures aimed at preventing discrimination and harassment.”

AppleOne, which placed 1,000 workers at Cardinal over two years, said in a statement it “did not control the workplace” but has implemented “improvements” to its policies ordered by the EEOC.

On a sunny morning in Rialto, Simmons, wearing a dashiki revealing forearm tattoos of a mermaid and a panther, was perplexed that the abuse at Cardinal Health had come from Latino colleagues. He choked up as he described his ordeal.

Leon Simmons said he complained to managers about poor treatment. “But nobody investigated,” he said. “Nobody cared.”

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

Growing up in Compton, Simmons had Mexican American friends. And over decades at other jobs — forklift driver, custodian, security guard — “Hispanics, whether they liked you or not, they kept it to themselves,” he said. As for the few white workers at Cardinal Health, “Never no problem with them,” he said.

AppleOne hired him to drive a cherry picker at Cardinal for $14 an hour, but he found Black workers were largely kept off the vehicles. Those jobs were given to less experienced Latino workers, even when licensed Black workers were first in line, he said.

Instead, Simmons, in his mid-50s, was given a harder floor picker job for $12 an hour, on his feet loading boxes headed for Kaiser Permanente hospitals. Temperatures inside the warehouse often rose past 90 degrees, he said.

It was six days a week, 14 to 16 hours a day, including mandatory overtime. He saw Latino workers clocking out after eight to 10 hours, but when Black workers asked to leave after 14 hours, they were often threatened with termination, Simmons said.

Leon Simmons voices his frustration with the racism he endured while working for Cardinal Health.

A Latino supervisor “would make me clean up the trash while everybody else was sent home.”

After three months of complaining, Simmons was allowed to drive a cherry picker, but his pay remained at $12 an hour, he said, lower than that of non-Black drivers.

He grew angry and despondent: “They’d write stuff on the bathroom walls — ‘gorillas, go back to Africa.’ The Black workers would cross it out. Two days later, it would be right back.”

Simmons complained to AppleOne and Cardinal managers, he said. “But nobody investigated. Nobody cared.” His Latina supervisor said, “If you’re up here complaining, the orders are not getting picked.”

Cardinal officials testified they received complaints about racial slurs, including graffiti with the N-word, but some emails documenting complaints and their responses were erased due to an auto deletion policy, even after EEOC charges were filed.

Black workers who complained “started disappearing one by one,” Simmons said. “We’d find out they were fired.” After 11 months, he too was told “your assignment is over.” No reason was given, he said.

By then, Simmons had started going to a psychologist. During visits, “I’d start shaking and crying,” he said. He was put on antidepressants.

Simmons got another job as a security guard but had to quit. The racism at Cardinal, he said, “messed me up. Something popped in my head. I was still having night terrors — waking up screaming.”

Today, diagnosed with PTSD, Simmons is on disability.

Last edited: