Food (Nri)

For black folks at the cookout, One-pot’ cooking practices, extra helpings of collard greens, a healthy incorporation of pepper, spices, and even “hot sauce” are not just random preferences.

Traditional soul food cooking is an inheritance which enslaved Africans passed on through their descendants once they were brought to the US. And this can be traced directly to Igbo cuisine.

Starting from the top clockwise: mashed potatoes, beans, collard greens, fried chicken

Many people are familiar with several staple foods that African Americans regularly consume such as rice, yam, black-eyed peas, watermelon, bananas, and plantains. But what a lot of people don’t know is that none of these foods listed are indigenous to the Americas.

During the Middle Passage, Western kidnappers intentionally took several crops native to Africa and made limited portions of these foods available on the ships in order to keep enslaved Africans alive. Once in the Americas, the enslaved Africans used their knowledge to continue to grow these crops on the plantations as food sources.

Frequently producing, consuming, and selling these crops, such as watermelon and black-eyed peas, these foods became tied to their identity and served as symbols of abolition and emancipation for free black people after the American Civil War. Some, such as watermelon, would also be turned into stereotypes via racist media portrayals.

Meanwhile in Igboland, during the course of all these events, the basic staple crops were primarily yams and palm oil. And secondarily: beans, green vegetables, cocoyams, papaws, plantains, bananas, okra, and watermelons.

Though the majority of these foods now show up in the Americas, descendants of Igbo at the time did not have the access to cultivate plantains, papaws, and bananas initially due perishability and the fact that those crops would be mainly brought to Central America once refrigerated ships were available. For African Americans, some of the stables such as palm-oil were replaced with butter and lard, while new staples such as maize and corn meal indigenous to America, were adopted entirely.

Yet still, the consumption of staples such as sweet and mashed potatoes in the Black Americans remains reminiscent of the consumption of pounded yam in West Africa. The frequent use of gravy for the consumption of mashed potatoes, vegetables, and cornbread by African-Americans is analogous to West Africans’ use of pounded yam and fufu (akpu) to devour stews and soups

In this picture, we can see that the diets are not all that different. Perhaps the main difference between African Americans today and Igbos is the latter’s traditional consumption using hands.

Okra commonly eaten as Soul food comes from the Igbo word “ọkwụrụ”. People in other parts of western Africa knew and grew the vegetable, But it was the Igbo expression that was the most common name that was Anglicized to ‘okra’ in the English language. Enslaved Africans frequently used okra to thicken stews and soups with even Thomas Jefferson adopting okra in his garden after learning from his African captives.

Africans arrivals in America commonly boiled greens in pork fat and seasoning with a combination of whatever vegetables were available at the time. This was no coincidence as there is nowhere is the frequent diet of leafy green vegetables more common than in Africa.

Even to this today, the recipe for Southern collard greens mirrors the recipe for steamed vegetable in Igboland. The ingredients for collard greens for Black Americans are: butter, chicken stock + garlic power, onion power, pepper, salt, and green vegetables.The ingredients for steamed vegetables in Igboland are: vegetable oil, Maggi stock: seasoning/spices, onion, pepper, salt, and green vegetables.

Language (Ásụ̀sụ̀)

Even with a clear relationship in dietary patterns, perhaps a more surprising example of Igbo inheritance is actually in language. The very part of identity most African Americans believe has been lost, is actually subtly present in the grammatical structure.

Most people assume that Black English or Ebonics is “poor English” due to a lack of education. But this Black English actually has a distinctive sets of grammar rules, structures, and sound patterns that are not random. This has been studied and analyzed as African American Vernacular English (AAVE).

Black English is more than just a vocabulary of cultural slangs and expressions like “Jive”, “Lit”, and “Straight Up”. There are grammatical nuances.

We take the following example comparing present simple and present continuous tenses:

Ebonics grammar is actually correct using Igbo grammar rules

If the “proper” English sentence of “We all live our lives” is translated word by word, based on American English rules, it produces a sentence that is actually incorrect under Igbo grammar rules.

The error occurs in the red highlight. The present verb tense “bi” translates to live momentarily instead of habitually. This implies a beginning and an end. Unlike in English where the present simple tense tells us something the speaker always does, In Igbo, the present tense shows an action taking place in the moment. For an Igbo person to denote lives as finite and measurable in a moment is a contradiction in the Igbo Cosmological worldview of life being continuous.

When we express the same concept into AAVE English, we obtain the continuous “lives” instead of “live”. And now when we translate this into Igbo based on English grammar rules, it actually corresponds exactly with the Igbo grammar structure.

In Igbo noun forms such as “ndụ” represent both plural “lives” and singular “life” which Igbo worldview sees as one and the same. Adding “s” to the “live” verb in this example corresponds with “is living” and this denotes a continuous living of the group. This is the present continuous tense is used in Igbo to show an action that is habitual and constant. This connotes with the Igbo identifying with spirit, instead of the physical body, which, in the Igbo worldview, has everlasting life.

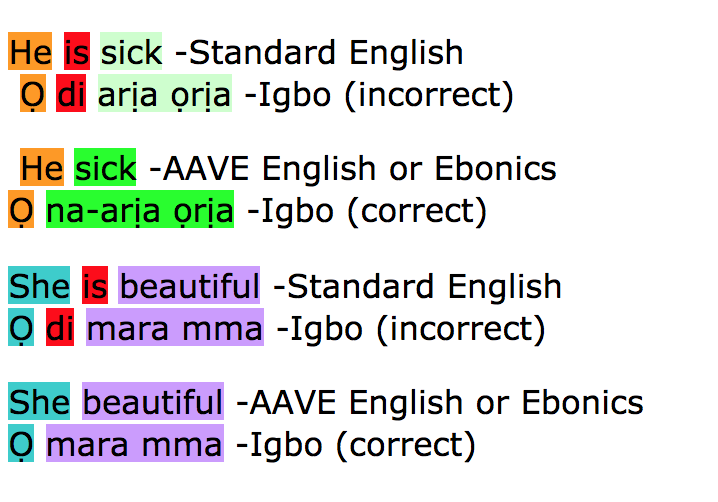

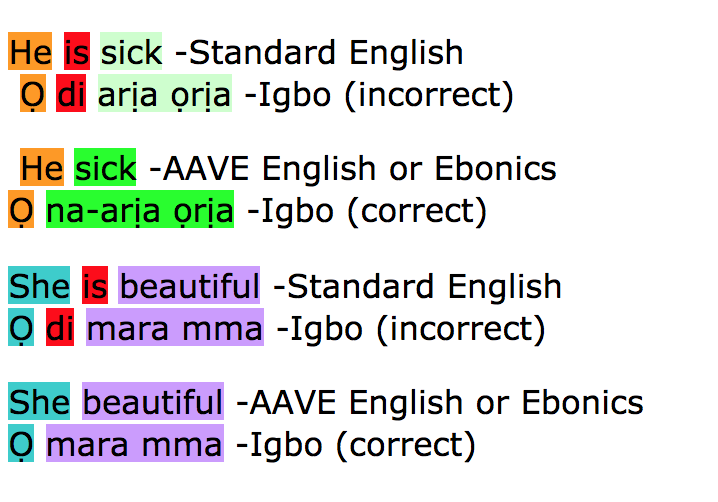

We investigate another example comparing the use of Copula Verbs:

English uses Copula Verbs in grammar for linking verbs from the subject to adjectives or subject compliments. In the first example of Standard English, “is”, the verb of to be, joins “He” and the adjective of “sick”. The same is true for joining “She” and “beautiful” with “is”. Under English grammar rules this is standard.

However, most African languages, including Igbo, do not use the copula verbs, before a qualifying adjectives. One attempting to use English grammar such as “Ọ dị arịa oria” for He is sick or “O di mara mma” for “She is beautiful” would receive confused looks from native Igbo speakers. As they intuitively can sense that this is incorrect speech under Igbo grammatical rules.

In Igbo and many African languages, the verb itself is applied directly to the subject without the need for a linking verb. This is shown in the case of “Ọ dị na-arịa oria” and “Ọ mara mma”. For this reason, when AAVE or Ebonics omits the joining verb of “is”, and says “He sick” or “She beautiful”, this is actually correct under Igbo grammar rules.

—

In the next blog, I will speak to more distinct Igbo cultural behaviors that have manifested in African-Americans.

Udoka the Afrikan – Medium

Igbo Amaka

..

For black folks at the cookout, One-pot’ cooking practices, extra helpings of collard greens, a healthy incorporation of pepper, spices, and even “hot sauce” are not just random preferences.

Traditional soul food cooking is an inheritance which enslaved Africans passed on through their descendants once they were brought to the US. And this can be traced directly to Igbo cuisine.

Starting from the top clockwise: mashed potatoes, beans, collard greens, fried chicken

Many people are familiar with several staple foods that African Americans regularly consume such as rice, yam, black-eyed peas, watermelon, bananas, and plantains. But what a lot of people don’t know is that none of these foods listed are indigenous to the Americas.

During the Middle Passage, Western kidnappers intentionally took several crops native to Africa and made limited portions of these foods available on the ships in order to keep enslaved Africans alive. Once in the Americas, the enslaved Africans used their knowledge to continue to grow these crops on the plantations as food sources.

Frequently producing, consuming, and selling these crops, such as watermelon and black-eyed peas, these foods became tied to their identity and served as symbols of abolition and emancipation for free black people after the American Civil War. Some, such as watermelon, would also be turned into stereotypes via racist media portrayals.

Meanwhile in Igboland, during the course of all these events, the basic staple crops were primarily yams and palm oil. And secondarily: beans, green vegetables, cocoyams, papaws, plantains, bananas, okra, and watermelons.

Though the majority of these foods now show up in the Americas, descendants of Igbo at the time did not have the access to cultivate plantains, papaws, and bananas initially due perishability and the fact that those crops would be mainly brought to Central America once refrigerated ships were available. For African Americans, some of the stables such as palm-oil were replaced with butter and lard, while new staples such as maize and corn meal indigenous to America, were adopted entirely.

Yet still, the consumption of staples such as sweet and mashed potatoes in the Black Americans remains reminiscent of the consumption of pounded yam in West Africa. The frequent use of gravy for the consumption of mashed potatoes, vegetables, and cornbread by African-Americans is analogous to West Africans’ use of pounded yam and fufu (akpu) to devour stews and soups

In this picture, we can see that the diets are not all that different. Perhaps the main difference between African Americans today and Igbos is the latter’s traditional consumption using hands.

Okra commonly eaten as Soul food comes from the Igbo word “ọkwụrụ”. People in other parts of western Africa knew and grew the vegetable, But it was the Igbo expression that was the most common name that was Anglicized to ‘okra’ in the English language. Enslaved Africans frequently used okra to thicken stews and soups with even Thomas Jefferson adopting okra in his garden after learning from his African captives.

Africans arrivals in America commonly boiled greens in pork fat and seasoning with a combination of whatever vegetables were available at the time. This was no coincidence as there is nowhere is the frequent diet of leafy green vegetables more common than in Africa.

Even to this today, the recipe for Southern collard greens mirrors the recipe for steamed vegetable in Igboland. The ingredients for collard greens for Black Americans are: butter, chicken stock + garlic power, onion power, pepper, salt, and green vegetables.The ingredients for steamed vegetables in Igboland are: vegetable oil, Maggi stock: seasoning/spices, onion, pepper, salt, and green vegetables.

Language (Ásụ̀sụ̀)

Even with a clear relationship in dietary patterns, perhaps a more surprising example of Igbo inheritance is actually in language. The very part of identity most African Americans believe has been lost, is actually subtly present in the grammatical structure.

Most people assume that Black English or Ebonics is “poor English” due to a lack of education. But this Black English actually has a distinctive sets of grammar rules, structures, and sound patterns that are not random. This has been studied and analyzed as African American Vernacular English (AAVE).

Black English is more than just a vocabulary of cultural slangs and expressions like “Jive”, “Lit”, and “Straight Up”. There are grammatical nuances.

We take the following example comparing present simple and present continuous tenses:

Ebonics grammar is actually correct using Igbo grammar rules

If the “proper” English sentence of “We all live our lives” is translated word by word, based on American English rules, it produces a sentence that is actually incorrect under Igbo grammar rules.

The error occurs in the red highlight. The present verb tense “bi” translates to live momentarily instead of habitually. This implies a beginning and an end. Unlike in English where the present simple tense tells us something the speaker always does, In Igbo, the present tense shows an action taking place in the moment. For an Igbo person to denote lives as finite and measurable in a moment is a contradiction in the Igbo Cosmological worldview of life being continuous.

When we express the same concept into AAVE English, we obtain the continuous “lives” instead of “live”. And now when we translate this into Igbo based on English grammar rules, it actually corresponds exactly with the Igbo grammar structure.

In Igbo noun forms such as “ndụ” represent both plural “lives” and singular “life” which Igbo worldview sees as one and the same. Adding “s” to the “live” verb in this example corresponds with “is living” and this denotes a continuous living of the group. This is the present continuous tense is used in Igbo to show an action that is habitual and constant. This connotes with the Igbo identifying with spirit, instead of the physical body, which, in the Igbo worldview, has everlasting life.

We investigate another example comparing the use of Copula Verbs:

English uses Copula Verbs in grammar for linking verbs from the subject to adjectives or subject compliments. In the first example of Standard English, “is”, the verb of to be, joins “He” and the adjective of “sick”. The same is true for joining “She” and “beautiful” with “is”. Under English grammar rules this is standard.

However, most African languages, including Igbo, do not use the copula verbs, before a qualifying adjectives. One attempting to use English grammar such as “Ọ dị arịa oria” for He is sick or “O di mara mma” for “She is beautiful” would receive confused looks from native Igbo speakers. As they intuitively can sense that this is incorrect speech under Igbo grammatical rules.

In Igbo and many African languages, the verb itself is applied directly to the subject without the need for a linking verb. This is shown in the case of “Ọ dị na-arịa oria” and “Ọ mara mma”. For this reason, when AAVE or Ebonics omits the joining verb of “is”, and says “He sick” or “She beautiful”, this is actually correct under Igbo grammar rules.

—

In the next blog, I will speak to more distinct Igbo cultural behaviors that have manifested in African-Americans.

Udoka the Afrikan – Medium

Igbo Amaka

..