Black Haven

We will find another road to glory!!!

How My Grandparents Helped Shape Chicago’s Blues Industry

By Arionne Nettles

April 27, 2019, 10:04 p.m. CT

In the 20th century, millions of black Americans who lived in southern states packed up and moved to northern cities — drawn by the promise of greater freedom and better jobs. Many headed to Chicago.

They brought a musical genre with deep African roots that reflected the realities of black life: the blues.

My granddaddy Narvel Eatmon and my grandma Bea Eatmon were among them. And when they established themselves in Chicago, they found success in the growing blues industry.

That’s one of the reasons I wanted to answer a question from Curious Citizen Charlie Davis, who asked:

What role did the Great Migration play in establishing the blues industry in Chicago?

During the time of the Great Migration, Chicago’s blues industry became by far the largest in the Midwest.

People like my grandparents helped build that industry. Their story reveals how the black community that came to Chicago during the Great Migration was able to take advantage of the city’s nightlife and established recording industry to make it their own.

Black people bring the blues to Chicago

Both my grandparents grew up in a place that was home to one of the earliest-known blues styles: Mississippi Delta Blues. They came from that Mississippi River culture and were immersed in the music of the region.

“The reason many people left Mississippi, and Alabama, and everywhere, is because they were tired of the circumstances there,” says my aunt Mary Brooks, who is our family’s unofficial historian. “So, they came north and they brought the blues with them.”

When they got to Chicago, they moved into the Black Belt on the South Side, which eventually spanned roughly between 12th and 79th streets and Wentworth and Cottage Grove avenues.

In the mid-20th century, the Black Belt was one of the few areas open to black tenants in Chicago. The area spanned roughly between 12th and 79th streets and Wentworth and Cottage Grove avenues on Chicago’s South Side. (Courtesy Newberry Library and University of Chicago Press)

My grandma was just 19 years old when she came to the city by herself. She was tired of picking cotton and, like many black Southerners, wanted an opportunity to work for better pay in one of Chicago’s large industries. She soon started working for the Dixie Cup Company.

My granddaddy, nicknamed Cadillac Baby, always had entrepreneurial dreams. He had just gotten out of the Army when he moved to Chicago. He met my grandma, and together they opened up a lounge at 47th and Dearborn called Cadillac Baby’s Show Lounge. There, they could stay close to the blues music they’d brought from the Jim Crow South while becoming a part of the city’s music and entertainment industry.

Entrepreneurs build upon an established recording industry

By the time my grandparents arrived in Chicago in the 1940s, there was already a vibrant recording industry that had been operating in Chicago for more than 20 years. The industry embraced the blues. Companies like Chess Records, started by Polish immigrants in 1950, would represent musicians like Muddy Watersand Howlin’ Wolf, who had themselves moved from Mississippi and Tennessee in 1943 and 1952, respectively.

Other music industry entrepreneurs, like my granddaddy, formed smaller but very important record labels that added to the city’s robust industry. He and my grandma started a recording company, Bea & Baby Records, in 1955. They recorded artists who would grow to become well-known at the time, like Little Mac, Hound Dog Taylor, Homesick James, and Eddie Boyd. Listen to one of their albums here.

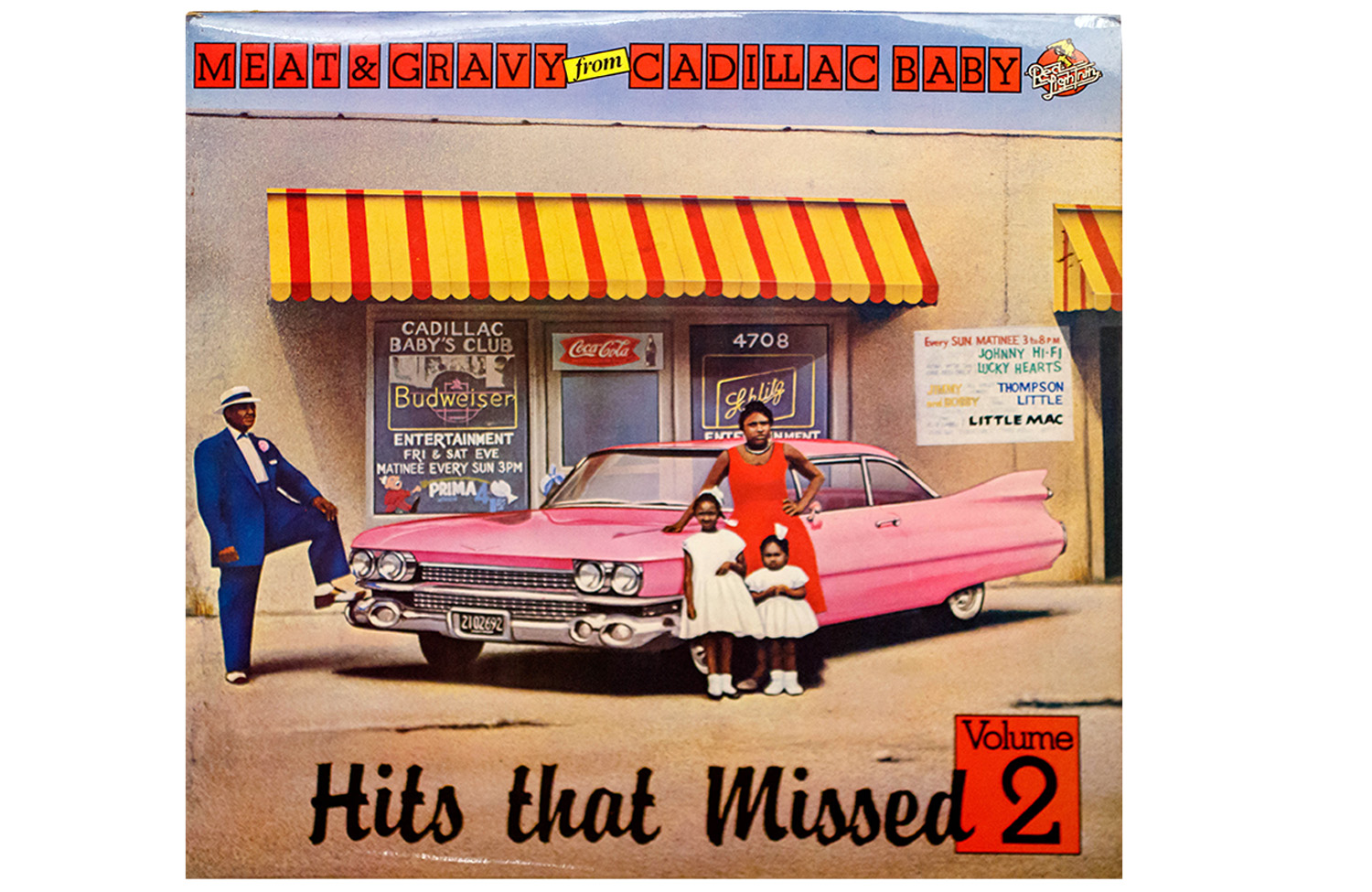

In 1955, my grandparents started a recording company called Bea & Baby Records. This compilation album includes songs originally released from 1959 through 1971. (WBEZ/Arionne Nettles)

It was during this postwar period through the 1960s that Chicago was starting to create its own blues subgenre. Musicians like Buddy Guy, Otis Rush and Freddie King changed both the sound and the lyrics to appeal to a more urbane, younger listener, says David Whiteis, author ofChicago Blues: Portraits and Stories.

“The postwar musicians began using electric guitars in the late ’40s, and within a few years, their sound, more or less, was what we’d now recognize as ‘electric Chicago blues.’” But, he adds, “there was a definite ‘roots/retro’ sound to the postwar Chicagoans, even after their full electric sound was being reproduced on records.”

Hustlers take advantage of the club scene

With its history of the Mafia, Prohibition, and paying folks to look the other way, the city was already prime for the blues industry to also grow into a nightlife ecosystem.

“We had loose liquor laws; we had mayors who allowed their police officers to take bribes and let the clubs open all night,” Whiteis says. “We had mayors that really permitted vast areas of the South Side to be basically centers for vice.”

So the blues, like several other Chicago industries, became “a hustlers’ industry.” My aunt says my granddaddy paid police officers and did whatever else he needed to do to keep the business going.

“Your grandpa was a hustler,” Whiteis says. “He wasn’t a gangster, but he was a hustler. He was out there making that money, and that was the name of the game.”

My grandparents worked tirelessly to keep their lounge successful: my granddaddy was the colorful face of the business while my grandma worked behind the scenes. (WBEZ/Arionne Nettles)