theworldismine13

God Emperor of SOHH

How an ex-FBI profiler helped put an innocent man behind bars

How an ex-FBI profiler helped put an innocent man behind bars

How an ex-FBI profiler helped put an innocent man behind bars

Exasperated, Jeffrey Ehrlich paused the true-crime television show every couple of minutes. The same thought kept running through the attorney’s mind: “No, that's wrong.”

The episode of “Killer Instinct” highlighted how the work of a retired FBI profiler had helped convict Ehrlich’s client of killing an 18-year-old woman in a Palmdale parking lot.

There were no fingerprints left behind, no murder weapon. But clues from the crime scene caught the profiler’s attention. The driver’s-side window of the victim’s car had been lowered several inches, suggesting to the profiler that the teen had rolled it down when someone who looked trustworthy approached. And her tube top was askew — a sign, the profiler said, of a botched sexual assault.

“No, no, no,” Ehrlich said, stopping the show again. He thought the episode — titled “Sudden Death” — needed a new name: “Here’s How We Convicted an Innocent Man of Murder.”

Years after the profiler’s testimony helped secure a murder conviction, the case against Ehrlich’s client, Raymond Lee Jennings, has unraveled in dramatic fashion.

After reinvestigating the case, authorities now suspect gang members killed Michelle O’Keefe and that the motive was robbery, not sexual assault. The profiler, Mark Safarik, has withdrawn his testimony. And a judge earlier this year declared Jennings — the security guard who patrolled the lot the night of the murder — factually innocent, putting a capstone on his legal nightmare that included 11 years behind bars.

Mark Safarik, a crime scene and behavioral analyst for Forensic Behavioral Services, gives testimony during the trial of Shadwick R. King during his trial in Illinois in 2015. (Sandy Bressner / Kane County Chronicle)

The wrongful conviction has renewed questions about the credibility of profiling and focused attention on the role played by Safarik, the star of the season-long television show “Killer Instinct,” whose testimony was considered crucial at Jennings’ trial.

In an interview with The Times, Safarik defended his analysis of the crime scene, saying he still harbors doubts about Jennings’ innocence. He agreed to withdraw his testimony, he said, after learning that homicide investigators hadn’t interviewed everyone who had been at the scene of the killing, but having the information wouldn’t have necessarily led him to a different conclusion.

In recent decades, profilers have captured the public’s imagination as the stars of a plethora of television shows and movies. In the real world, they work to help detectives predict the likely characteristics of a criminal in an unsolved case and explain to jurors how evidence left at crime scenes can reveal a killer’s motive or modus operandi.

But there is a deep chasm in legal and academic circles about how much credibility to give profilers. Many detectives credit them with helping investigations, but some researchers have criticized profiling as nothing more than glorified guesswork.

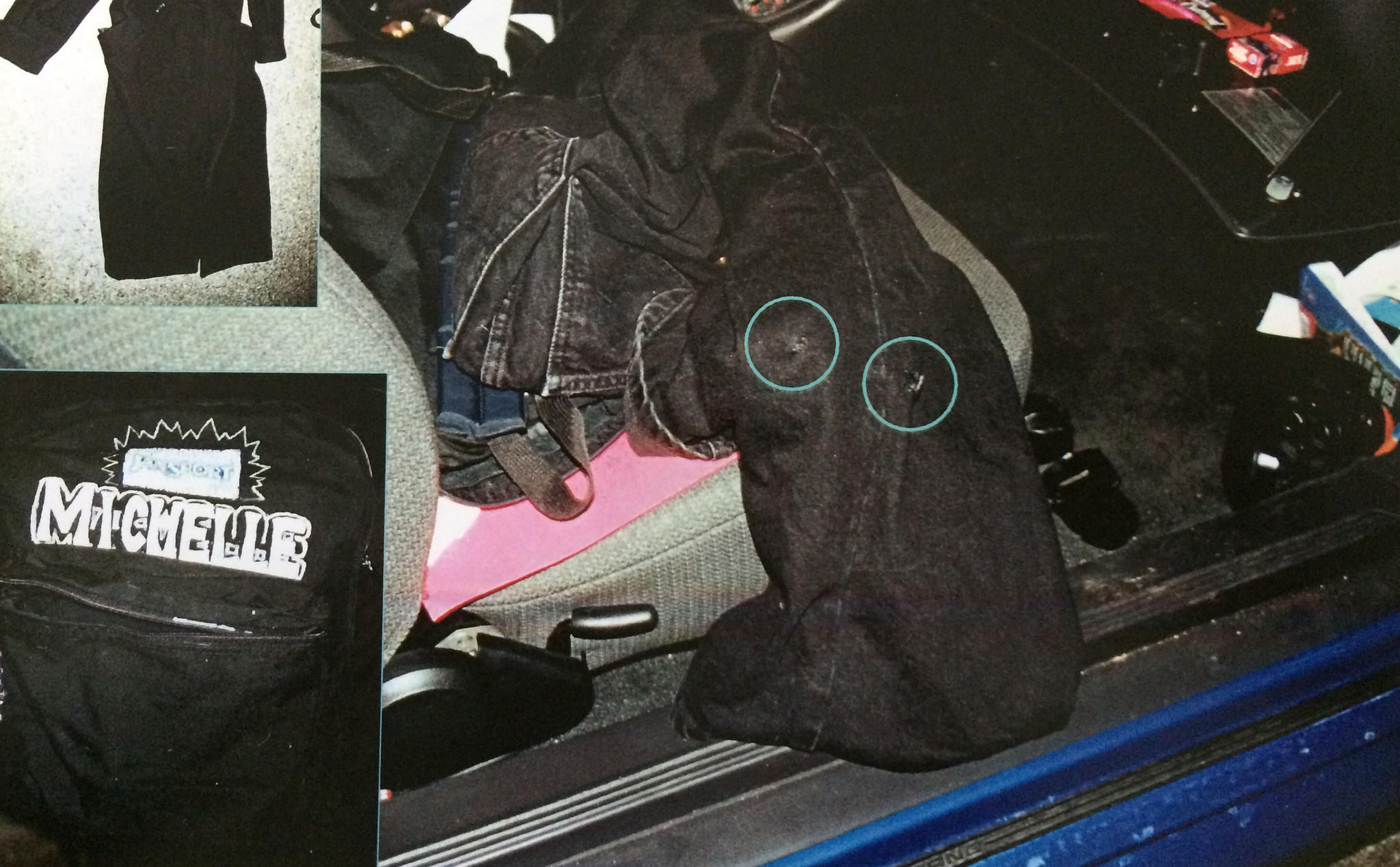

Clockwise from top left: Photo of Jennings' security guard uniform presented as evidence in court, which showed no blood or gun powder residue. Evidence photo of blood spatter that investigators found inside Michelle O’Keefe’s blue Mustang. Photo presented as evidence in court of items found inside her car, and a crime scene photo of the Mustang. (Los Angeles Superior Court)

The murder

It was 2006 and Safarik would soon retire from the FBI, but not before looking into the 6-year-old murder case of O’Keefe. The college student died after bullets tore through her head and neck as she sat in her blue Mustang in a desolate park-and-ride lot patrolled by a security guard.

Michelle O'Keefe.

Safarik spent more than a decade in Quantico, Va., studying crime scene evidence and writing offender profiles in serial killings, sexual assaults and stalking cases. In the O’Keefe investigation, Los Angeles prosecutors wanted two things from him: An assessment of crime scene evidence from the Feb. 22, 2000, shooting and an opinion on the killer’s motive.

Jennings was arrested in 2005, but the case against him was thin, based only on circumstantial evidence. No blood or gunpowder was found on his security guard uniform, and male DNA under the victim’s fingernails didn’t match his.

In a report written shortly after his retirement in 2007, Safarik stopped short of identifying Jennings as the killer but noted some of the same inconsistent statements by the security guard that had initially raised the suspicion of detectives.

Jennings, for instance, initially denied seeing any cars leave the lot after the shooting. Later, he admitted he’d spoken to a female driver who had stopped to ask him what happened as she drove away. The security guard also told investigators he saw O’Keefe’s body “twitching” when he arrived at her car several minutes after the shooting — something a forensic pathologist said was “beyond the limits of credibility.”

A prosecutor argued at trial that Jennings had lied to cover up his involvement in the crime. Two separate juries in downtown L.A. deadlocked before the case was moved to the Antelope Valley for a third and last trial.

Safarik, who testified in all three, was the prosecution’s final witness in the third. He told jurors he’d assessed or reviewed at least 4,000 crime scenes — many of them complex homicide cases — and had written numerous articles and book chapters.

“When you start to look at that many cases,” he told jurors, “you start to see patterns in behavior.”

Safarik explained to jurors how he'd eliminated several possible motives for O’Keefe’s murder.

(Los Angeles County Superior Court)

He stressed there was no history of gang crime in the lot and said it didn’t appear to be a targeted personal attack, noting that O’Keefe didn't have a boyfriend or a criminal record. Robbery didn't make sense, he said, noting that O’Keefe’s wallet containing more than $100 was left in her car, and that her blue Mustang wasn’t taken. And, the parking lot was lighted and patrolled by a guard.

The blood spatter at the scene, he told jurors, showed that the killer had first confronted O’Keefe as she stood outside her car. Her tube top was pulled down, he noted, partially exposing her breasts.

“I believe that the motive for this crime was sexual assault,” Safarik said. “It went bad quickly and it escalated into a homicide.”

The prosecutor argued that Safarik’s testimony explained a clear motive for Jennings to kill O’Keefe: He panicked after attempting to sexually assault her.

During deliberations, jurors asked to be read back Safarik’s testimony. After more than three weeks, the jury convicted Jennings of second-degree murder.

At his sentencing hearing in 2010, Jennings — who always maintained his innocence — was given 40 years to life in prison.

“This is one sin,” he told the court, “that I will not be judged for.”

Raymond Lee Jennings, right, attends a hearing in Los Angeles. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Inside the mind of a killer

The idea of trying to get inside a killer’s mind stretches back centuries, but the modern popularity of profiling began in the 1970s with the creation of an FBI team now known as the Behavioral Analysis Unit.

The unit’s agents — officially called behavioral analysts — are trained to predict the personality traits and actions of an offender during an investigation by drawing on research of past cases and interviews with violent criminals.

There is very little scientific research testing the reliability of profiling, and the few existing studies have led to sharp disagreements over whether profilers can better predict the characteristics of criminals than nonprofilers.

Still, the public holds an outsized view of what profilers can do, said David Wilson, a professor of criminology at Birmingham City University in England who has written critically about profiling. Due in large part to shows such as “CSI” and “Criminal Minds,” as well as the film “Silence of the Lambs,” the public often views profilers as omniscient Sherlock Holmes-esque experts who can quickly identify a killer and decipher the motive, he said.

“We want to believe in that Holmesian figure that can turn up and magically solve the crime,” Wilson said.

California’s courts generally don’t allow testimony comparing a defendant to the characteristics of a “typical” criminal out of fear that such a profile could easily include innocent people. Judges do, however, often allow profilers to testify about crime scene evidence and what it reveals about possible motives, modus operandi or links to similar crimes by a common perpetrator.