RESEARCH

Hollywood writers went on strike to protect their livelihoods from generative AI. Their remarkable victory matters for all workers.

Molly KinderApril 12, 2024

TV writer Jackie Penn | Photo credit: Phil Cheung

Growing up in a working-class immigrant family in Queens, N.Y., Danny Tolli dreamed of a career in television. “I was a storyteller straight out of the womb,” Tolli told me in November. After studying film and television at New York University, he worked his way up in Hollywood, starting out as an assistant a decade ago and rising to a TV writer and co-executive producer today.

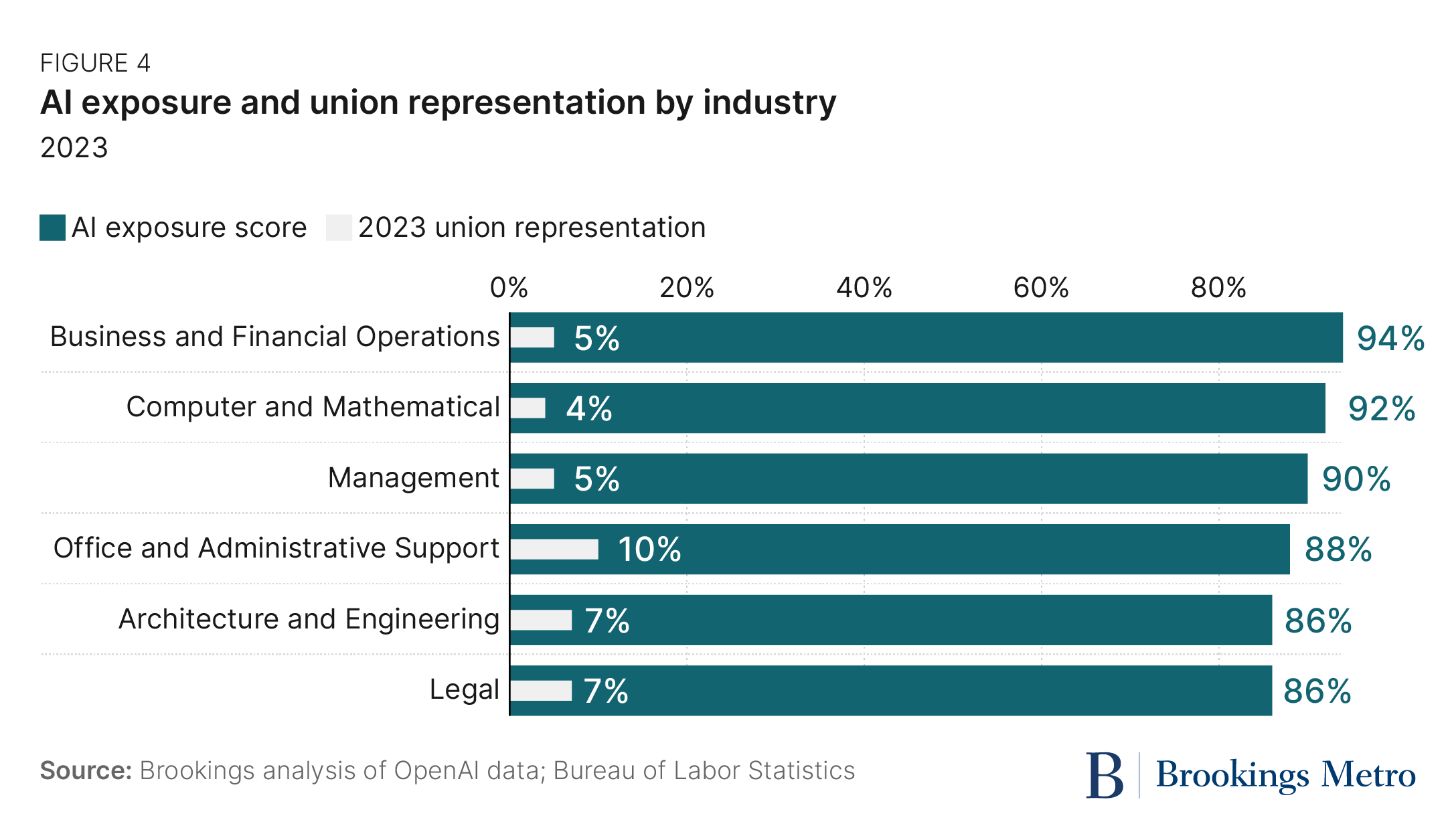

Until last year, Tolli—like most of us—never imagined that artificial intelligence might threaten his career. For decades, automation has concentrated in the kinds of routine, blue-collar jobs he grew up around. Highly creative and cognitive roles—like writing the stories that shape our culture—were considered to have a low risk of disruption.

OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT 3.5 at the end of 2022 turned that paradigm on its head. Seemingly overnight, the generative AI chatbot captured the public’s attention by excelling at precisely the kinds of non-routine skills that have long been considered quintessentially “human.”

“It’s scary…We were watching in real time how it was starting to generate ideas, storylines, and scenes,” said Tolli. He pointed to one of AI’s defining features: its rapid expected increase in capabilities. “It’s not doing a great job [now], but ChatGPT 6 might do an even better job,” he said.

Workers and AI: Voices from the front lines of disruption

In this ongoing series, Brookings Metro introduces you to workers in occupations that will likely face disruption from generative AI, including writers, legal assistants, illustrators, accountants, and customer service representatives.In their own words, these workers will share what they feel is at stake as well as the risks and opportunities AI presents. Their stories are accompanied by in-depth case studies exploring AI’s effect on these industries and what policymakers, employers, and each of us can do to enable workers to benefit from AI and avoid potential harm.

Hear from five Hollywood writers, in their own words »

Read about the project »

Meet the Hollywood writers: Danny Tolli, co-executive producer; Leah Folta, TV story editor; David Goodman, executive producer; Raphael Bob-Waksberg; Showrunner; Jackie Penn, TV writer | Photo credit: Phil Cheung and David Walter Banks

For the first time, Tolli worried that Hollywood studios would use the new technology to replace writers and destroy the ladder he had been climbing. A lot was suddenly at stake: a career he felt he was born to do, the economic security that eluded his parents, and the kind of American Dream that had long been possible for successful Hollywood writers. Also at stake was the greater diversity and inclusion reflected in the newest generation of Hollywood writers, and the kinds of stories they could tell.

As Tolli’s fears grew, his union, the Writers Guild of America West, was in the middle of negotiating a three-year contract with the biggest studios in Hollywood. In just a matter of months, AI’s potential threat shot from obscurity to rallying cry for Tolli and thousands of fellow writers who went on strike in spring 2023. Among their list of demands were protections from AI—protections they won after a grueling five-month strike.

The contract the Guild secured in September set a historic precedent: It is up to the writers whether and how they use generative AI as a tool to assist and complement—not replace—them. Ultimately, if generative AI is used, the contract stipulates that writers get full credit and compensation. The victory was important for Tolli, but its implications reverberate far beyond Hollywood.

Reflecting on the strike, Tolli said:

With AI a central issue in our contract negotiation, we felt very much like the canary in the coal mine. That we were announcing to all workers and union members across the country that if these studios are going to use automation to replace screenwriters, what’s stopping them from taking your jobs?

Over the past several months, I interviewed Tolli and other Hollywood writers to document their fears and aspirations surrounding generative AI’s impact on their careers, and capture their stories from the front lines of this issue. (You can read more of their stories here.)

Table of contents

Hollywood writing: A coveted career under strain from technology-driven shifts »Generative AI: What is at stake for Hollywood writers »

Generative AI: What is at stake for society »

The labor strike and groundbreaking contract: What was achieved—and how »

Lessons for other unions and workers in industries poised for AI disruption »

This report explores what is at stake for both writers and our society, what these writers were able to achieve in their contract negotiations, and what we can learn from this experience in terms of shaping the way AI is deployed in our economy. That Hollywood writers became the first and most visible face of resistance to generative AI speaks volumes about the nature of this new technology and the kinds of livelihoods that it will impact most. Their victory in securing first-of-their-kind protections offers important lessons for other unions and professional organizations, policymakers, and workers across a range of occupations who may face similar disruptions to their careers.

Danny Tolli, co-executive producer | Photo credit: Philip Cheung

Hollywood writing: A coveted career under strain from technology-driven shifts

A successful career writing in Hollywood has many hallmarks of a “dream” job: coveted, well paid, and exciting. Writing jobs in Hollywood are highly sought after and extremely competitive, if also unpredictable.Leah Folta, a TV writer and story editor, reflected on the personal significance of her craft:

I love writing. I love all of it: the producing, the collaborating in the room, the way you get to exercise the muscles that we have in production and making sure things are executed the way you want. It is such a huge gift and so much fun. I don’t have a backup career, because I never wanted any.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, writers and authors in the motion picture and video industry earned an average annual wage of $136,690 in 2022, compared to an average of $61,900 for all job occupations in our economy. But pay varies widely by seniority and role, and Hollywood writers operate like independent contractors, seeking TV employment seasonally and selling movie scripts in a freelance fashion. Writers contend with rejected scripts, canceled shows, and periods of unemployment.

Minimum pay for Hollywood writers is negotiated by the union: the East and West branches of the Writers Guild of America (WGA). The WGA represents approximately 11,500 TV and movie writers and bargains on the sector level—meaning with all the major studios as a group, not company by company—through the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). The AMPTP represents more than 350 film and television producers, including major studios such as Amazon, Apple, Discovery, Disney, NBCUniversal, Netflix, Paramount, Sony, and Warner Bros. Discovery. The WGA negotiates three-year contracts with the AMPTP that stipulate base compensation, staffing, residuals (when a show or film is reused), and other terms of employment for their members.

Here’s how it works, starting with feature films as an example. Feature film writers are compensated based on the product, type of writing, and budget of the film. The highest minimum pay of just over $160,000 is for an original screenplay for a high-budget film, and just over half this amount for a low-budget film. The lowest minimum payments are for “polishes” (which are less extensive than a full script rewrite) and for having a story (a summary of a film idea, but not a full script) included in a screenplay. Established screenwriters can command compensation that substantially exceeds these minimums rates.

Writing staff on TV shows are paid a weekly rate, by role, for a set number of weeks corresponding to a show’s season. The lowest-paid writer in the union—the staff writer—earns a minimum of $4,362 per week before fees and taxes. A writer-producer could earn about twice as much, and higher-ranked roles earn even more.

While early-career writers may struggle to make ends meet, traditionally, the most senior writers who have ascended the career ladder in film and television have been well compensated.

David A. Goodman, a TV writer with 35 years of experience and credits that include executive producer of “Family Guy,” underscored the arc of his good fortune when compared to that of the single parent who raised him on a modest income.

Certainly, when I entered the business [in 1988], if you could establish yourself as a writer in Hollywood, it led to a comfortable lifestyle. The pay was good. If you could continue to get work, you would get promotions and pay increases. It allowed me to have a life that was a much more comfortable one than I had a child. I was raised by a single mom who was a social worker in New York…There was a lot of financial anxiety in my family.

Goodman’s career allowed him to buy a home in Los Angeles, send his children to private school, take annual vacations, financially support struggling family members, and consistently pay his bills. He credited the WGA with enabling his longevity in the industry and providing stability during cyclical periods of financial difficulty.

In addition to union-provided health insurance and retirement benefits, Goodman cited the importance of residuals, which the union championed in successive contracts. Residuals are financial compensation paid out when a TV show or film is “reused,” such as through syndication, cable reruns, or licensing to a streaming platform. Goodman said that during periods of unemployment after a canceled shows or between seasons, residual checks would occasionally appear in the mail and help him keep his family afloat and continue to pay his bills until he was able to secure his next writing job.