get these nets

Veteran

Global Boston is a digital project chronicling the history of immigration to greater Boston since the early nineteenth century. Examining different time periods and ethnic groups, the site features capsule histories, photographs, maps, documents, and oral histories documenting the history of a city where immigrants have long been a vital force in shaping economic, social and political.

Boston University 2016

==============================

Cape Verdeans

Cape Verdean Student Association of Boston College celebrating publication of a new Cape Verdean Kreyol-English dictionary, 2016. Courtesy of Daija Carvalho/Mili-Mila.com.

Cape Verdeans

Settled by Portuguese in the mid-fifteenth century, the Cape Verde archipelago consists of ten arid islands off the coast of Senegal in West Africa. As the Portuguese imported slave labor from the mainland, the islands soon became a center of the slave trade and a provisioning point for ships traveling along the African coast. In the mid-nineteenth century, severe drought conditions and poverty drove many former slaves and mixed-race Cape Verdeans to seek work on whaling ships plying the Atlantic. Some later settled in the whaling port of New Bedford, setting in motion a migrant stream to southeastern Massachusetts that peaked between 1890 and 1921. Coming mainly from the islands of Brava and Fogo, the early migrants were disproportionately male, often migrating seasonally on packet ships run by Cape Verdean companies.

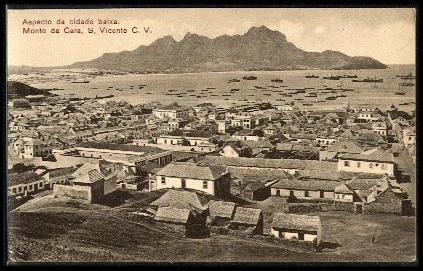

Postcard showing the Cape Verdean island of Saõ Vincente, early 20th century.

Migration declined dramatically in the early 1920s under US immigration restriction and tight Portuguese controls on Cape Verdean emigration. Even after passage of the 1965 Immigration Act, emigration rates remained low; it was not until the Republic of Cape Verde won its independence in 1975 that foreign visas became more widely accessible. By the 1980s, Cape Verdeans would be migrating across Europe, Brazil, and the US, but particularly to New England, which was well known because of its historic connections to the islands.

The new immigrants differed in many ways from the old. Their island origins have been more diverse—they come not only from Brava and Fogo but also from Saõ Tiago, Saõ Vicente, and Saõ Nicolau. The gender ratio of the new wave has been much more balanced, and the newcomers also include the more prosperous and educated as well as the poor.

Settlement

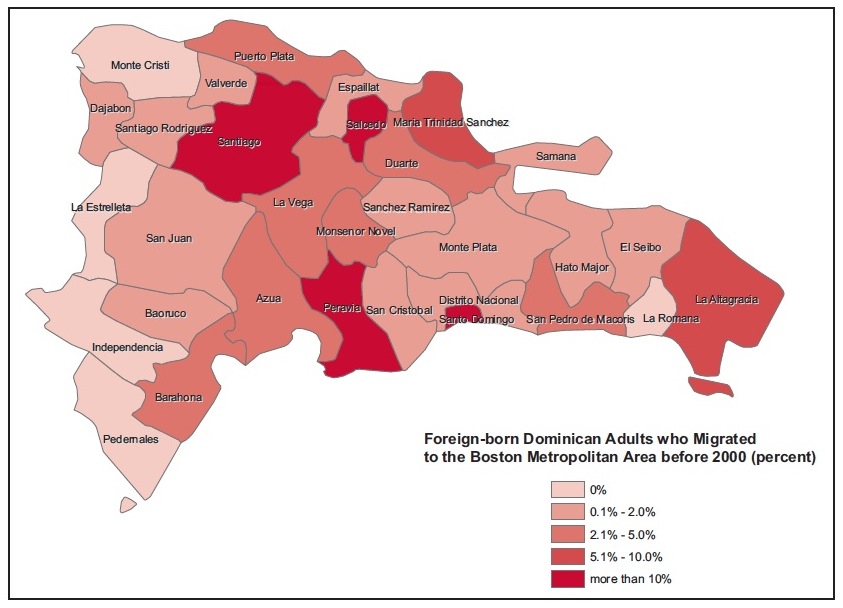

During the first wave of migration, most Cape Verdeans settled in New Bedford, as well as in adjacent areas of southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Over the course of the twentieth century, a small migrant community developed in Boston, but most of the city’s Cape Verdean population has arrived since 1975. Coming earlier than other African national groups (who mainly arrived after 1990), Cape Verdeans are the city’s largest African group and the sixth largest foreign-born group overall. Constrained by racial discrimination and segregation, Cape Verdeans have settled in predominantly black and Latino areas of Roxbury and Dorchester, especially in the area between Dudley Square and Upham’s Corner. The city of Brockton, an older industrial city located between Boston and New Bedford, has been another key settlement area, with Cape Verdeans making up roughly a third of the city’s foreign-born population in 2014.

Work

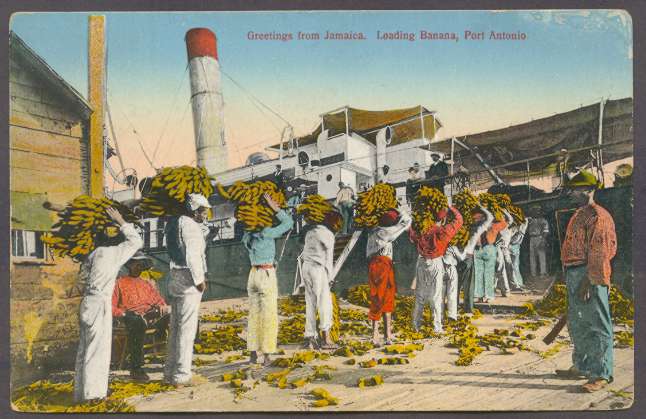

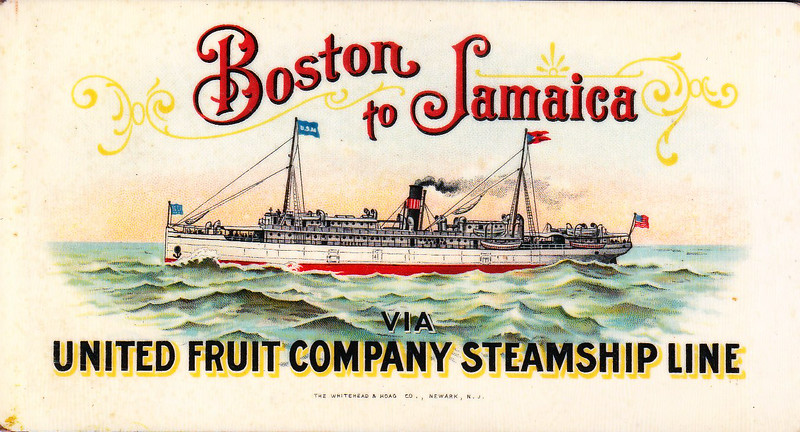

With the decline of whaling in the late nineteenth century, Cape Verdean immigrants moved into maritime jobs on the docks and on merchant ships, as well as doing seasonal agricultural work picking cranberries in southeastern Massachusetts. A smaller number found work in New Bedford’s textile mills, but usually in less desirable, lower-paying positions.

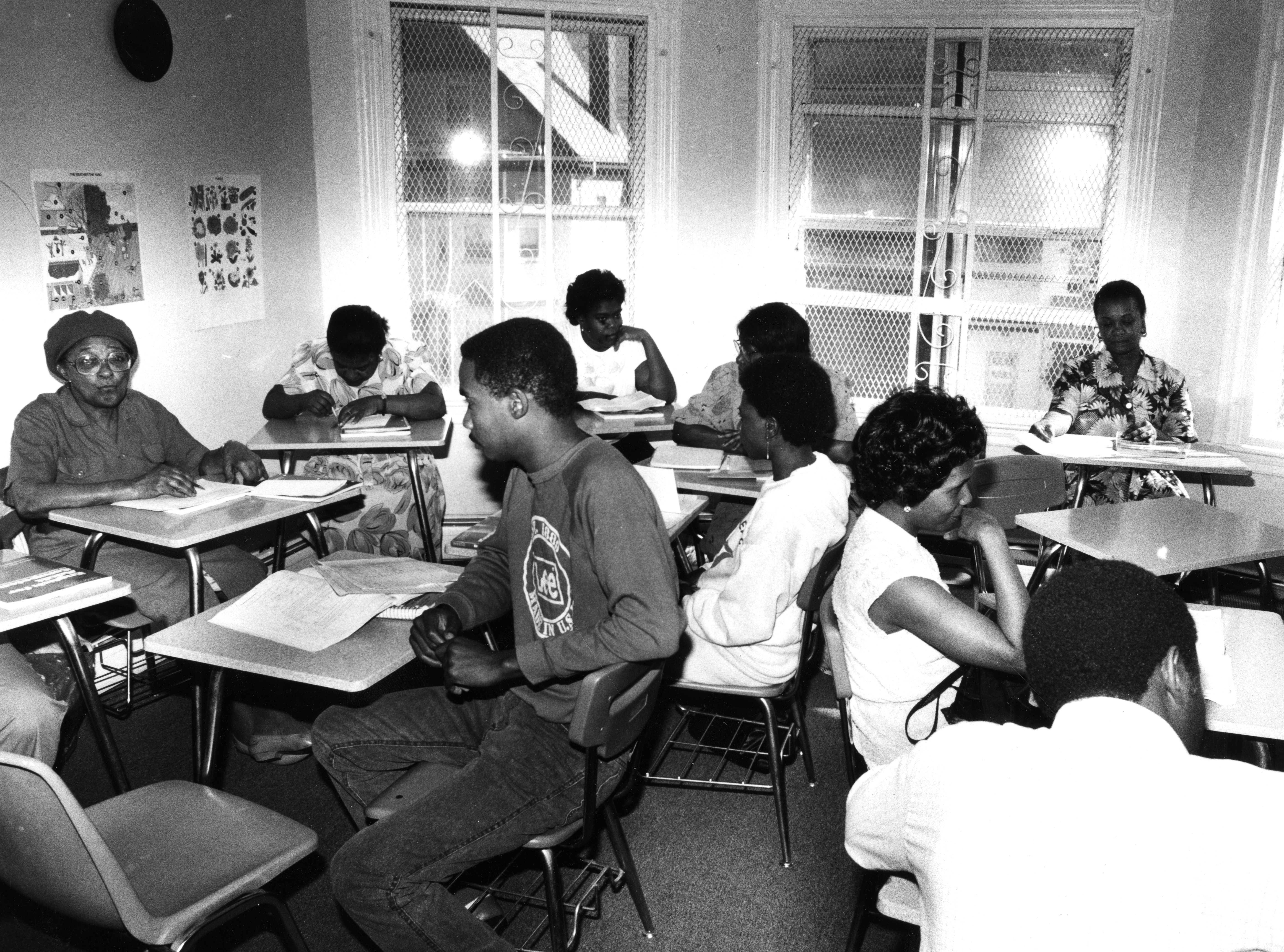

The second wave of Cape Verdean arrivals also initially found work in factories in the Boston and Brockton areas, but gradually moved into the service industries as manufacturing plants closed down. Although Cape Verdean immigrants have not been known for occupying particular employment niches, they have developed a vibrant small business sector of restaurants, groceries, real estate and insurance offices, and other enterprises. In recent years, the second generation has also been moving into professional, managerial, and civil service occupations.

Last edited: