Obviously I haven't put forth the energy to make a historical beefs post in a long time, but various ideas kept passing through my mind of ones I wanted to do. So I'm just going post a lot of half-assed ones here as I get the time, and anyone interested can take advantage.

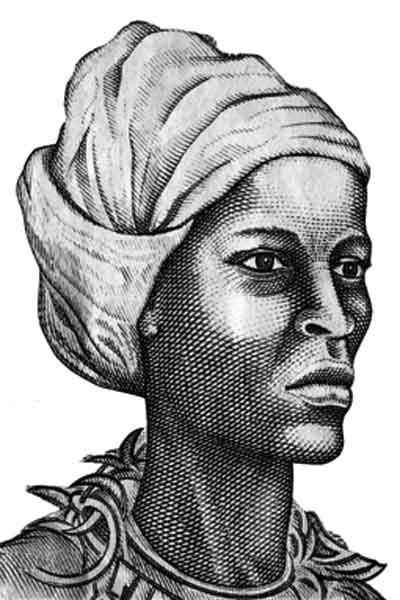

Queen Nanny was a Jamaican slave who escaped her British masters, fled to the mountains, and became a powerful rebel leader.

Or she never was a slave because she jumped from the slave ship before it reached dock and swam to join the free Maroons.

Or she boarded the ship in Africa on her own, a free woman of royal blood, and came of her own volition to marry a freeman farmer.

Truth is there's a lot of shyt we don't know about Queen Nanny, aka Granny Nanny, aka Nanny of the Maroons. She was born in the 1670s or 1680s, was shot to death in 1733 or stabbed in her tent in 1734 or killed by a cannonball in 1738 or died peacefully 10 years after the war in 1750 or of old age in the 1760s, was either a brilliant, practical military strategist or a full-on obeah woman whose victories came from mystical powers which included the ability to catch cannonballs with her ass and fire them back on British troops.

Wait wah?

There are a few things we DO know about Queen Nanny. She was almost certainly not born in Jamaica but was an Ashanti, of the Akan, what today would be situated in Ghana. One way or another, a ship brought her to the island, and one way or another she joined up with the Maroons living in the most difficult mountain terrain. She claimed royal blood, rose to head of the free peoples of Jamaica, and scared the living daylights out of those British.

Back up just a moment and let's set this stage.

From the earliest times of slavery in 1500s Jamaica, Black slaves were able to escape and flee to the hills, where they found a welcoming jungle terrain whose inhospitality made it difficult for the Spanish to get them back. For over a century their numbers grew, they formed their own communities and civilization, trading with and even intermarrying with the local Taino / Arawak people. When the British defeated the Spanish in 1655 and took the island, many Spanish freed their slaves and the ranks of the Maroons grew. Over the course of British occupation more slaves continued to escape and join the Maroons, sometimes in revolts 300 or 400 strong, to the point where they had 5 full-fledged towns in the jungles on both ends of Jamaica. The eastern and western ends were governed separately, and by the early 1700s, Granny Nanny had risen to the head and unified the eastward group.

Queen Nanny's rule terrified the British. She raided their settlments at will, but going into Maroon territory could get a soldier killed by all sorts of traps. Nanny is credited with teaching the Maroons to use cow horns with holes to communicate over long distances, enabling them to coordinate both attack and defense. Her spy networks covered the island and there were even plantation slaves loyal to Nanny who fed her information on British plans. She employed cameoflage masterfully, enabling her mud-and-stick covered raiders to get to the very edge of British towns undetected, where they would suddenly rush in with fire and take supplies or free more slaves.

Despite the fear with which the specter of Nanny inflicted on British soldiers, the best evidence is that she did not lead troops into battle herself, but instead operated as a political, spiritual, and strategic leader. Quao, the other major leader of the Eastward Maroons and sometimes rumored to be Nanny's brother, appears to have been their primary on-site military general.

In 1728 the British decided they had had enough and the King sent thousands of troops to Jamaica to stomp out Nanny and the Maroons. Overwhelming firepower changed the equation and made life difficult for the Maroons, with Nanny's own town being occupied several times. But her people were masters of guerrila warfare. When towns were overrun the population dissolved into the countryside and minimized casualties. Traps were constant, with the British frequently chasing small fleeing groups into narrow canyons only to find entire regiments waiting there to ambush them.

In 1734 the British burned down Nanny Town and declared that they had defeated the dreaded obeah woman, but in fact her forces appear to have simply melted back into the hills, and in short order came back even stronger. At their height Nanny is said to have been commanding 3,000 Maroon soldiers, though they were too strategic to ever engage the British in open warfare, sticking to guerrilla tactics where they maintained the advantage. Throughout 1735-1737 the Maroon counterattacks on British settlements became constant, and the colonizers began to realize that they were stuck in an unwinnable war. Edward Trelawny reached Jamaica as the colonial governor in 1738 and immediately began working towards peace negotiations. In 1739 and 1740, treaties were signed and the Maroons were granted land on both sides of the island. After 85 years of constant conflict and 12 years of all-out war, they no longer had to fight - they were free.

50 years before the American colonists did it, a relatively small band of free Black Jamaicans had defeated the most powerful military force on the planet.

Before the war ended the British claimed to have killed Nanny multiple times, and yet they have a record of signing a land deal with her in 1741 (the last official record mentioning her by name). The Maroons did not keep their own written records, and the oral tradition is confusing to say the least. No stories of her post-war activities survive, though there are conflicting accounts of the year she may have died. Some writers even theorize that there was more than one "Nanny" leading the Maroons during that First Maroon War, with the original female leader who had terrorized the British with raids for decades perhaps being killed in the early 1730s, only to have others rise up in her place. None of the Maroons' own stories support this possibility.

Over the next 150 years the actions of the Maroons left them a complex legacy. But for Black peoples in the Carribean, their success in taking their place as a free community was an inspiring legacy. Fifty years after the Maroons won their land, Toussaint Louverture looked at what they had done and said, "If they could do it, we can too."

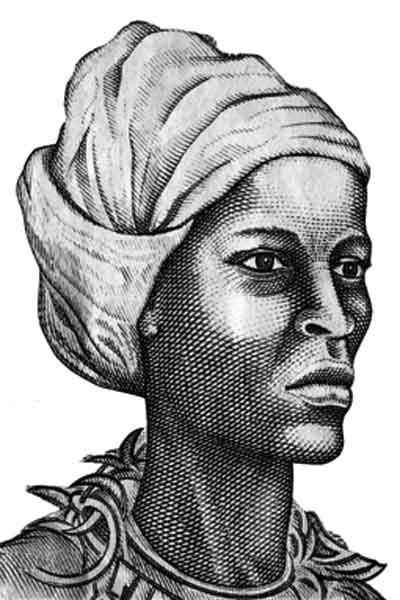

Queen Nanny was a Jamaican slave who escaped her British masters, fled to the mountains, and became a powerful rebel leader.

Or she never was a slave because she jumped from the slave ship before it reached dock and swam to join the free Maroons.

Or she boarded the ship in Africa on her own, a free woman of royal blood, and came of her own volition to marry a freeman farmer.

Truth is there's a lot of shyt we don't know about Queen Nanny, aka Granny Nanny, aka Nanny of the Maroons. She was born in the 1670s or 1680s, was shot to death in 1733 or stabbed in her tent in 1734 or killed by a cannonball in 1738 or died peacefully 10 years after the war in 1750 or of old age in the 1760s, was either a brilliant, practical military strategist or a full-on obeah woman whose victories came from mystical powers which included the ability to catch cannonballs with her ass and fire them back on British troops.

Wait wah?

There are a few things we DO know about Queen Nanny. She was almost certainly not born in Jamaica but was an Ashanti, of the Akan, what today would be situated in Ghana. One way or another, a ship brought her to the island, and one way or another she joined up with the Maroons living in the most difficult mountain terrain. She claimed royal blood, rose to head of the free peoples of Jamaica, and scared the living daylights out of those British.

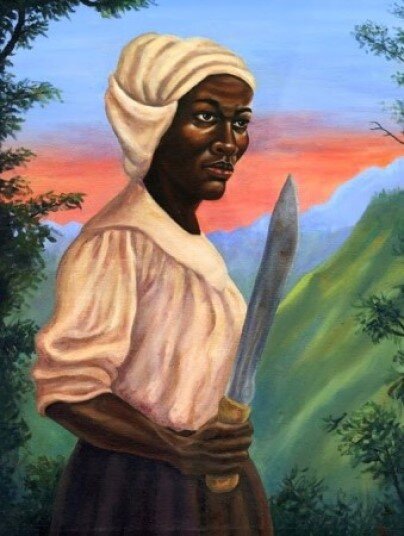

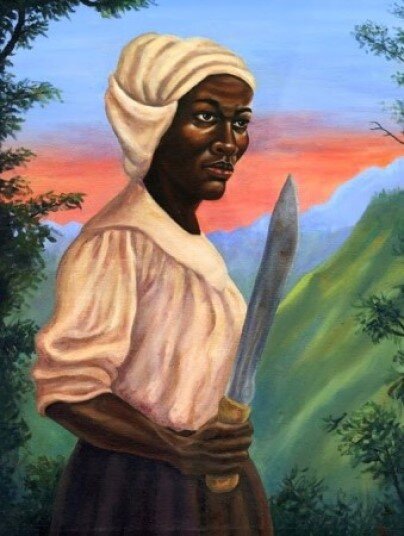

"A girdle around her waist with nine or ten knives hanging in it, many of which no doubt have been plunged into human flesh and blood." - Captain Philip Thicknesse

Back up just a moment and let's set this stage.

From the earliest times of slavery in 1500s Jamaica, Black slaves were able to escape and flee to the hills, where they found a welcoming jungle terrain whose inhospitality made it difficult for the Spanish to get them back. For over a century their numbers grew, they formed their own communities and civilization, trading with and even intermarrying with the local Taino / Arawak people. When the British defeated the Spanish in 1655 and took the island, many Spanish freed their slaves and the ranks of the Maroons grew. Over the course of British occupation more slaves continued to escape and join the Maroons, sometimes in revolts 300 or 400 strong, to the point where they had 5 full-fledged towns in the jungles on both ends of Jamaica. The eastern and western ends were governed separately, and by the early 1700s, Granny Nanny had risen to the head and unified the eastward group.

Queen Nanny's rule terrified the British. She raided their settlments at will, but going into Maroon territory could get a soldier killed by all sorts of traps. Nanny is credited with teaching the Maroons to use cow horns with holes to communicate over long distances, enabling them to coordinate both attack and defense. Her spy networks covered the island and there were even plantation slaves loyal to Nanny who fed her information on British plans. She employed cameoflage masterfully, enabling her mud-and-stick covered raiders to get to the very edge of British towns undetected, where they would suddenly rush in with fire and take supplies or free more slaves.

Despite the fear with which the specter of Nanny inflicted on British soldiers, the best evidence is that she did not lead troops into battle herself, but instead operated as a political, spiritual, and strategic leader. Quao, the other major leader of the Eastward Maroons and sometimes rumored to be Nanny's brother, appears to have been their primary on-site military general.

In 1728 the British decided they had had enough and the King sent thousands of troops to Jamaica to stomp out Nanny and the Maroons. Overwhelming firepower changed the equation and made life difficult for the Maroons, with Nanny's own town being occupied several times. But her people were masters of guerrila warfare. When towns were overrun the population dissolved into the countryside and minimized casualties. Traps were constant, with the British frequently chasing small fleeing groups into narrow canyons only to find entire regiments waiting there to ambush them.

In 1734 the British burned down Nanny Town and declared that they had defeated the dreaded obeah woman, but in fact her forces appear to have simply melted back into the hills, and in short order came back even stronger. At their height Nanny is said to have been commanding 3,000 Maroon soldiers, though they were too strategic to ever engage the British in open warfare, sticking to guerrilla tactics where they maintained the advantage. Throughout 1735-1737 the Maroon counterattacks on British settlements became constant, and the colonizers began to realize that they were stuck in an unwinnable war. Edward Trelawny reached Jamaica as the colonial governor in 1738 and immediately began working towards peace negotiations. In 1739 and 1740, treaties were signed and the Maroons were granted land on both sides of the island. After 85 years of constant conflict and 12 years of all-out war, they no longer had to fight - they were free.

50 years before the American colonists did it, a relatively small band of free Black Jamaicans had defeated the most powerful military force on the planet.

Before the war ended the British claimed to have killed Nanny multiple times, and yet they have a record of signing a land deal with her in 1741 (the last official record mentioning her by name). The Maroons did not keep their own written records, and the oral tradition is confusing to say the least. No stories of her post-war activities survive, though there are conflicting accounts of the year she may have died. Some writers even theorize that there was more than one "Nanny" leading the Maroons during that First Maroon War, with the original female leader who had terrorized the British with raids for decades perhaps being killed in the early 1730s, only to have others rise up in her place. None of the Maroons' own stories support this possibility.

Over the next 150 years the actions of the Maroons left them a complex legacy. But for Black peoples in the Carribean, their success in taking their place as a free community was an inspiring legacy. Fifty years after the Maroons won their land, Toussaint Louverture looked at what they had done and said, "If they could do it, we can too."