Houston’s zoning has left them defenseless.

Those kinds of blindsiding evictions are a rootshock that many renter families in New Orleans know too well, as the same happened for Hurricane Katrina. Plenty of New Orleanians didn’t even get a notice—instead they found out via TV that they would not be able to return to their homes. This certainly was true for tenants of the city’s “Big Four” public housing projects, which were closed for good during Katrina even though many of them collected no floodwaters.

This is the kind of displacement that Kelley fights to help families avoid, through his nonprofit Community In-Power and Development Association(CIDA), which advocates on behalf of families living under the constant threat of environmental disasters.

That doesn’t just mean flooding and hurricanes. Port Arthur is saturated with oil refineries and petrochemical plants, many of them located within yards of homes, schools, and playgrounds. The Carver Terrace public housing projects in Port Arthur were completely surrounded by these poisonous industries before they were torn down just last year, which Kelley had been petitioning the federal government to do for years. All of Carver Terrace’s tenants were relocated, to finally remove them from the clouds of air pollution molesting their lungs and nostrils every day.

That kind of displacement was necessary—requested, even, from the tenants themselves. The involuntary kind of displacement, however, that’s becoming a more frequent event in Port Arthur due to heavier and harsher storms, is getting harder for Kelley to weather. He contemplated for a moment not returning to his home and restaurant that he runs after his most recent evacuation from Harvey. He changed his mind only after considering what he’d lose and how difficult it would be starting over in another city.

“There are sharks out there waiting for us to let loose what we have here and swoop in as we migrate out,” says Kelley. “Industries will just engulf this land and then we’ve lost what we’ve owned. I own property here. When I leave here, I don’t own anything in Dallas, or Colorado, or New York. And I can’t imagine trying to buy a restaurant or a home there in this present situation.”

Displacement like this is increasingly becoming inevitable for people of color, not just because of climate change and extreme weather events, but because of discriminatory policies that push them into unlivable conditions. It’s a reality that is rarely confronted when it comes time to map out where people can and can’t rebuild. But ignoring it likely means that policies for rebuilding will suffer from the same disparities that have predated recent storm recoveries by several decades.

The problem of displacement is even more pronounced for Latinos. At the same time that Harvey was devastating the land, Trump decided to recall DACA, which put thousands of immigrant children at even greater risk. If Congress approves Trump’s request, then those children will face the kind of relocation that doesn’t just send them to another city, but rather, to a detention center, and then to another country that they, in many cases, have no real connection to, if they grew up in the U.S.

Bryan Parras, an organizer with Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (t.e.j.a.s), is working a lot these days with Latino families who are bracing for recovery from both Harvey and Trump’s restrictive immigration policies. Displacement is a threat that always lurks around Latino communities, and their options for sanctuary are growing more limited, especially as new storms keep gathering in the Gulf.

“That’s what disaster does—it really destroys the fabric of a community and that’s even deeper destruction, because it’s psychological, it’s spiritual, it’s cultural,” says Parras. “Even if they stay, that place is different. It’s been traumatized, so staying doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be able to maintain those cultural ties to your neighbors.”

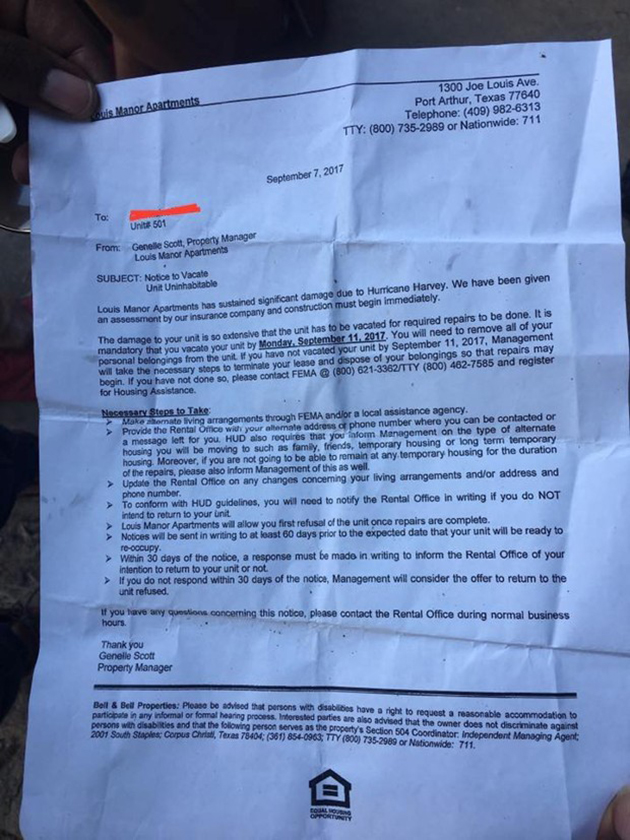

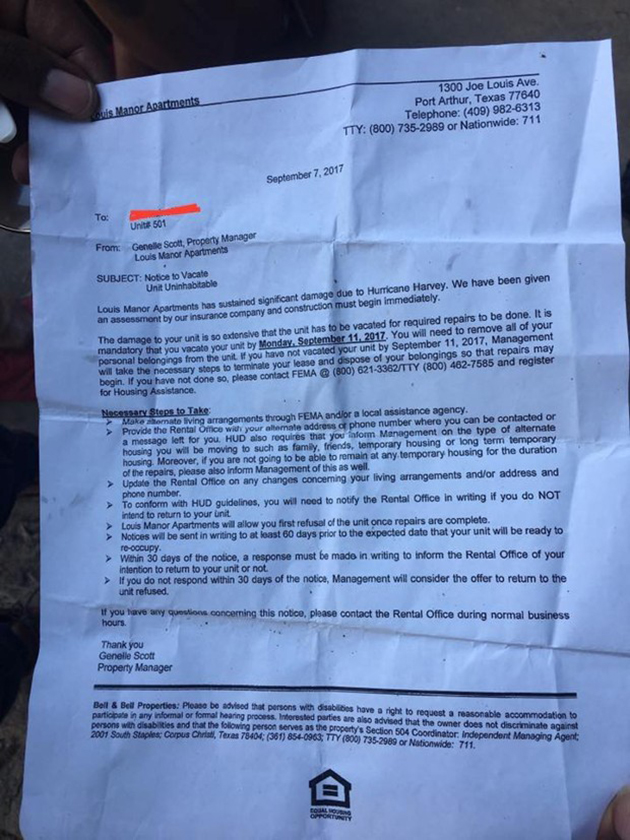

Hilton Kelley has been sounding off on Facebook Live the past few days about families who evacuated their homes to escape Hurricane Harvey and are now getting eviction notices. The families live in Port Arthur, Texas, the small Gulf Coast city about 90 miles east of Houston, but are currently scattered across Louisiana and Texas. Kelley himself had to evacuate—his fourth time doing so in the last 15 years due to hurricane flooding—but was able to make it back to his home last week. He’s now trying to locate as many dispersed families as possible via social media to find out who hasn’t come back and why. That’s when he found out about the eviction notices.

Those kinds of blindsiding evictions are a rootshock that many renter families in New Orleans know too well, as the same happened for Hurricane Katrina. Plenty of New Orleanians didn’t even get a notice—instead they found out via TV that they would not be able to return to their homes. This certainly was true for tenants of the city’s “Big Four” public housing projects, which were closed for good during Katrina even though many of them collected no floodwaters.

This is the kind of displacement that Kelley fights to help families avoid, through his nonprofit Community In-Power and Development Association(CIDA), which advocates on behalf of families living under the constant threat of environmental disasters.

That doesn’t just mean flooding and hurricanes. Port Arthur is saturated with oil refineries and petrochemical plants, many of them located within yards of homes, schools, and playgrounds. The Carver Terrace public housing projects in Port Arthur were completely surrounded by these poisonous industries before they were torn down just last year, which Kelley had been petitioning the federal government to do for years. All of Carver Terrace’s tenants were relocated, to finally remove them from the clouds of air pollution molesting their lungs and nostrils every day.

That kind of displacement was necessary—requested, even, from the tenants themselves. The involuntary kind of displacement, however, that’s becoming a more frequent event in Port Arthur due to heavier and harsher storms, is getting harder for Kelley to weather. He contemplated for a moment not returning to his home and restaurant that he runs after his most recent evacuation from Harvey. He changed his mind only after considering what he’d lose and how difficult it would be starting over in another city.

“There are sharks out there waiting for us to let loose what we have here and swoop in as we migrate out,” says Kelley. “Industries will just engulf this land and then we’ve lost what we’ve owned. I own property here. When I leave here, I don’t own anything in Dallas, or Colorado, or New York. And I can’t imagine trying to buy a restaurant or a home there in this present situation.”

Displacement like this is increasingly becoming inevitable for people of color, not just because of climate change and extreme weather events, but because of discriminatory policies that push them into unlivable conditions. It’s a reality that is rarely confronted when it comes time to map out where people can and can’t rebuild. But ignoring it likely means that policies for rebuilding will suffer from the same disparities that have predated recent storm recoveries by several decades.

The problem of displacement is even more pronounced for Latinos. At the same time that Harvey was devastating the land, Trump decided to recall DACA, which put thousands of immigrant children at even greater risk. If Congress approves Trump’s request, then those children will face the kind of relocation that doesn’t just send them to another city, but rather, to a detention center, and then to another country that they, in many cases, have no real connection to, if they grew up in the U.S.

Bryan Parras, an organizer with Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (t.e.j.a.s), is working a lot these days with Latino families who are bracing for recovery from both Harvey and Trump’s restrictive immigration policies. Displacement is a threat that always lurks around Latino communities, and their options for sanctuary are growing more limited, especially as new storms keep gathering in the Gulf.

“That’s what disaster does—it really destroys the fabric of a community and that’s even deeper destruction, because it’s psychological, it’s spiritual, it’s cultural,” says Parras. “Even if they stay, that place is different. It’s been traumatized, so staying doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be able to maintain those cultural ties to your neighbors.”