mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

This is a long but super informative read about how fukked Hollywood currently is. Read if you want, or ignore, but this is impacting you all:

harpers.org

harpers.org

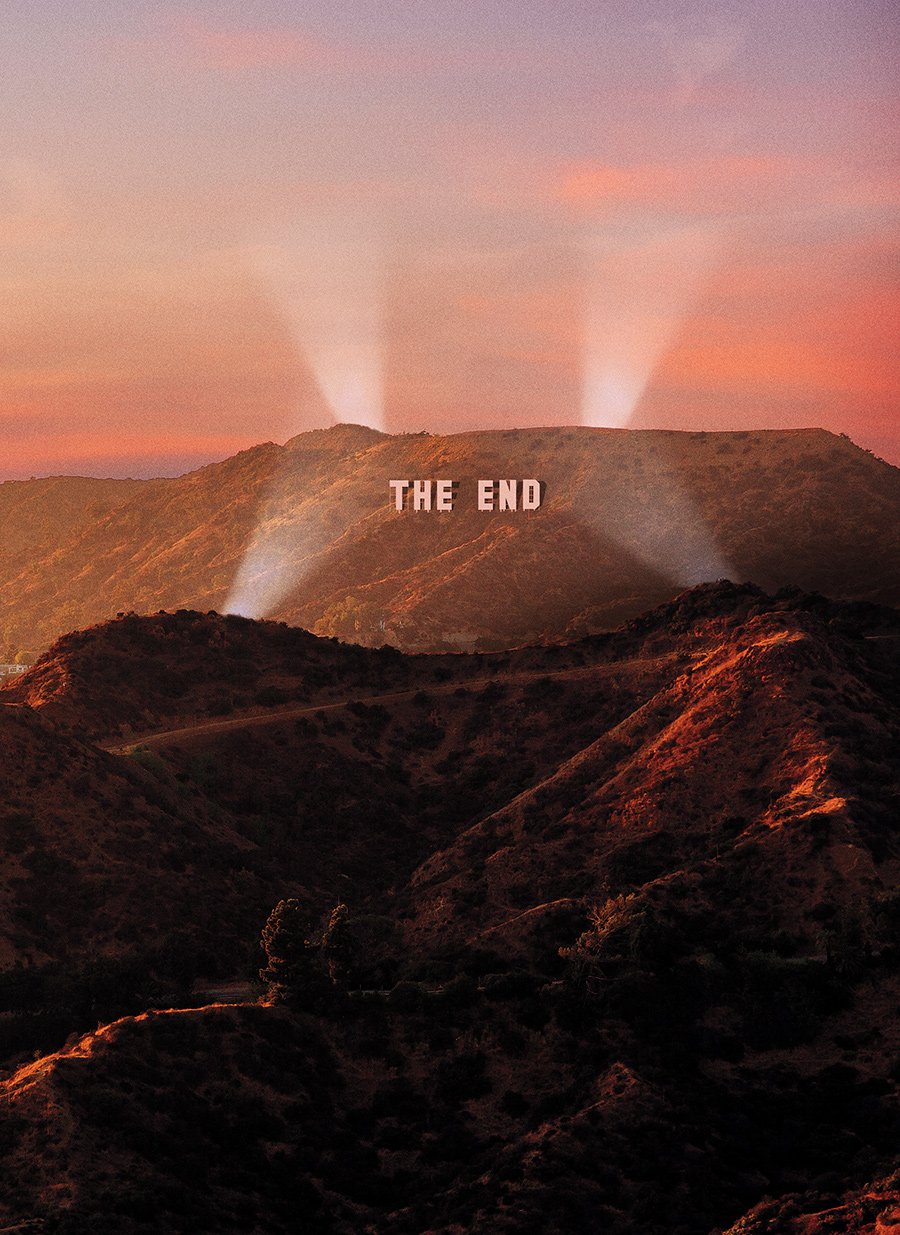

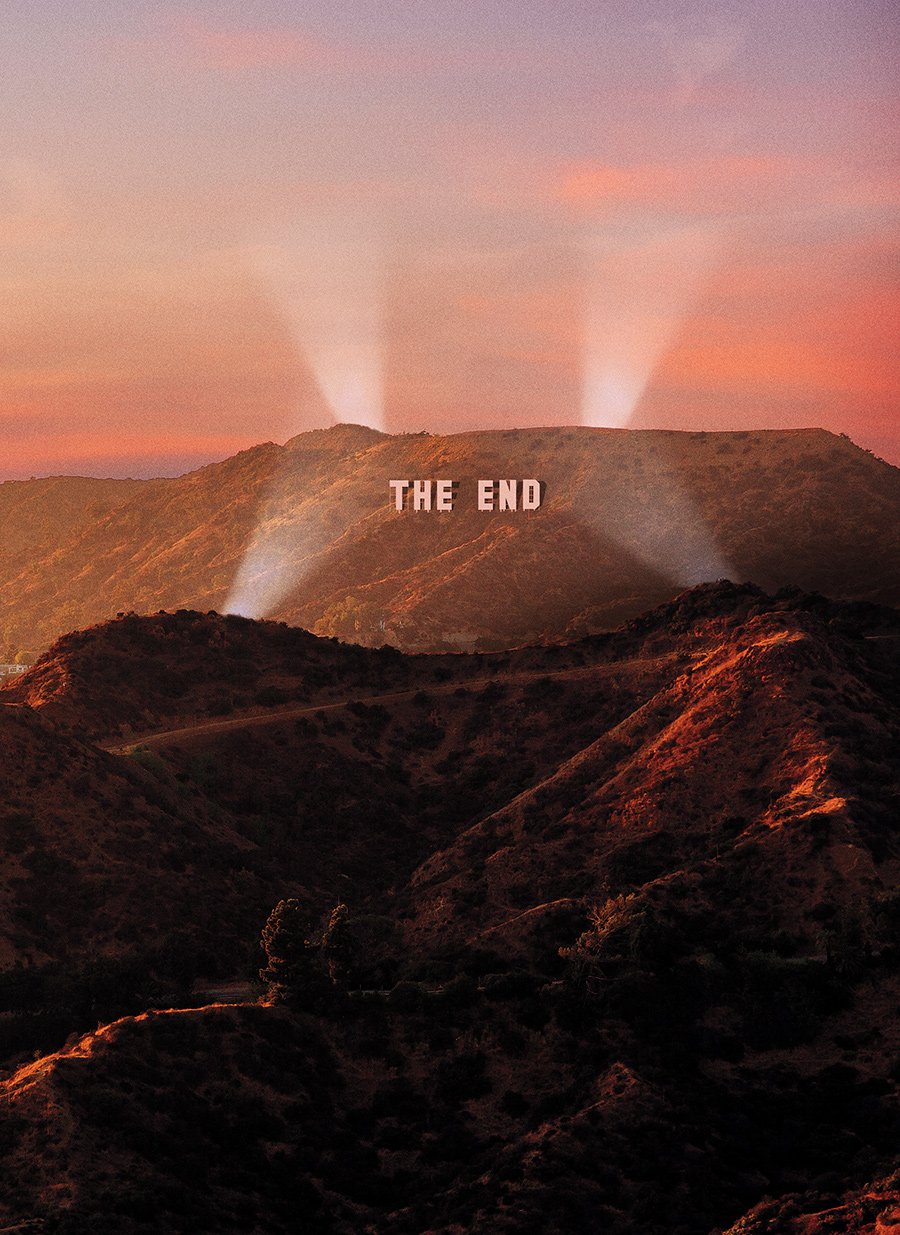

The Life and Death of Hollywood, by Daniel Bessner

Film and television writers face an existential threat

...In 2012, at the age of thirty-two, the writer Alena Smith went West to Hollywood, like many before her. She arrived to a small apartment in Silver Lake, one block from the Vista Theatre—a single-screen Spanish Colonial Revival building that had opened in 1923, four years before the advent of sound in film.

Smith was looking for a job in television. She had an MFA from the Yale School of Drama, and had lived and worked as a playwright in New York City for years—two of her productions garnered positive reviews in the Times. But playwriting had begun to feel like a vanity project: to pay rent, she’d worked as a nanny, a transcriptionist, an administrative assistant, and more. There seemed to be no viable financial future in theater, nor in academia, the other world where she supposed she could make inroads.

For several years, her friends and colleagues had been absconding for Los Angeles, and were finding success. This was the second decade of prestige television: the era of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Homeland, Girls. TV had become a place for sharp wit, singular voices, people with vision—and they were getting paid. It took a year and a half, but Smith eventually landed a spot as a staff writer on HBO’s The Newsroom, and then as a story editor on Showtime’s The Affair in 2015.

I first spoke with Smith in August of last year, four months into the strike called by the Writers Guild of America against the members of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), the biggest Hollywood studios. In 2013, she’d begun to develop the idea for what would become dikkinson, a gothic, at times surreal comedy based on the life of the poet, Emily. “I realized you could do one of those visceral, sexy, dangerous half hours but make it a period piece,” she said. “I was never trying to write some middle-of-the-road thing.” She sold the pilot and a plan for at least three seasons to Apple in 2017; she would be the showrunner, and the series had the potential to become one of the flagship offerings of the company’s streaming service, which had not yet launched.

Looking back, Smith sometimes marvels that dikkinson was made at all. “It centers an unapologetic, queer female lead,” she said. “It’s about a poet and features her poetry in every episode—hard-to-understand poetry. It has a high barrier of entry.” But that was the time. Apple, like other streamers, was looking to make a splash. “I mean, they made a show out of I Love dikk,” Smith said, referring to the small-press cult classic by Chris Kraus, adapted into a 2016 series for Amazon Prime Video. “That doesn’t happen because people are using profit as their bottom line.”

In fact, they weren’t. The streaming model was based on bringing in subscribers—grabbing as much of the market as possible—rather than on earning revenue from individual shows. And big swings brought in new viewers. “It’s like a whole world of intellectuals and artists got a multibillion-dollar grant from the tech world,” Smith said. “But we mistook that, and were frankly actively gaslit into thinking that that was because they cared about art.”

Making a show for Apple was not what she’d hoped it would be. What the company wanted from her and the series never felt clear—there was a “radical information asymmetry,” she said, regarding management’s priorities and metrics. After she and her colleagues completed the first season of dikkinson, they waited for the streamer to launch and the show to air. Their requests for a firm timeline and premiere date were ignored. Smith started to worry that Apple might scrap the idea for the streaming platform altogether, in which case the show might never be seen, or might even disappear—she didn’t have a copy of the finished product. It belonged to Apple and lived on the company’s servers.

“It was communicated to me,” Smith said, “that my only choice to keep the show alive was to begin all over again and write a whole new season without a green-light guarantee. So I was expected to take on that risk, when the entities that stood to profit the most from the success of my creative labor, the platform and studio, would not risk a dime.” “It was also on me,” she went on, “to kind of fluff everybody involved in the entire making of the show, from the stars to the line producer to the costume designer, etcetera, to make them believe that we’d be coming back again and prevent them, sometimes unsuccessfully, from taking other jobs.”

Finally, in late 2019, when Smith and her colleagues were two months into production on Season 2, the show premiered as one of the streamer’s four original series. It was an immediate critical success and a sensation on social media. “In Apple TV+’s initial smattering of shows,” wrote the Washington Post, “only ‘dikkinson’ is a delicious surprise.” It received a 2019 Peabody Award; in 2021 it made the New York Times’ list of best programs of the year and won a Rotten Tomatoes prize for Fan Favorite TV Series.

But Smith was losing steam. “I was only allowed to make the show to the extent that I was willing to take on unbelievable amounts of risk and labor on my own body perpetually, without ceasing, for years,” she said. “And I knew that if I ever stopped, the show would die.” It had seemed to her that Apple didn’t value the series, and she felt at a loss. Smith now knows that dikkinson was the company’s most-watched show in its second and third seasons. But at the time, she had no access to concrete information about its performance. As was the habit among streamers, Apple didn’t share viewership data with its writers. And without that data, Smith had no leverage. In 2020, after three seasons, she told Apple that she was done. “I said, I can’t do it anymore. And Apple said, Okay.”

“Passion can only get you so far,” she told me. But she’d stayed in Hollywood. “I’m an artist,” she said, “and I’m never going to stop creating.” The industry was still the only place one could make a real living as a writer. “When people say, Why stay in TV?” she said, “The answer is, There is nothing else. What do you mean?”

...Financial institutions could snatch up or take over large portions of companies in any area of the business; they could even acquire or substantially invest in groups in competition with one another—and they did, creating types of soft monopoly. Bets were even placed against the traditional industry as a whole, in the form of investments in Netflix, which promised to disrupt and dominate at-home viewing. Today the Big Three asset-management firms hold the largest stakes in most rival companies in media and entertainment. As of the end of last year, Vanguard, for example, owned the largest stake in Disney, Netflix, Comcast, Apple, and Warner Bros. Discovery. It holds a substantial share of Amazon and Paramount Global. By 2010, private-equity companies had acquired MGM, Miramax, and AMC Theatres, and had scooped up portions of Hulu and DreamWorks. Private equity now has its hands in Univision, Lionsgate, Skydance, and more.

In the years following the recession, there was, as Howard Rodman put it, “a slow erosion” in feature-film writers’ ability to earn a living. To the new bosses, the quantity of money that studios had been spending on developing screenplays—many of which would never be made—was obvious fat to be cut, and in the late Aughts, executives increasingly began offering one-step deals, guaranteeing only one round of pay for one round of work. Writers, hoping to make it past Go, began doing much more labor—multiple steps of development—for what was ostensibly one step of the process. In separate interviews, Dana Stevens, writer of The Woman King, and Robin Swicord described the change using exactly the same words: “Free work was encoded.” So was safe material. In an effort to anticipate what a studio would green-light, writers incorporated feedback from producers and junior executives, constructing what became known as producer’s drafts. As Rodman explained it: “Your producer says to you, ‘I love your script. It’s a great first draft. But I know what the studio wants. This isn’t it. So I need you to just make this protagonist more likable, and blah, blah, blah.’ And you do it.”

damn breh that a deep question but I think the ones that are going to answer it will be the younger millennials and zoomers the older Generation like the boomer and Gen x are too bake in on how things use to work when it come to film and tv.

damn breh that a deep question but I think the ones that are going to answer it will be the younger millennials and zoomers the older Generation like the boomer and Gen x are too bake in on how things use to work when it come to film and tv.