Gene therapy restores hearing to children with inherited deafness

The first clinical trial to administer gene therapy to both ears in one person has restored hearing function to 5 children born with a form of inherited

Gene therapy restores hearing to children with inherited deafness

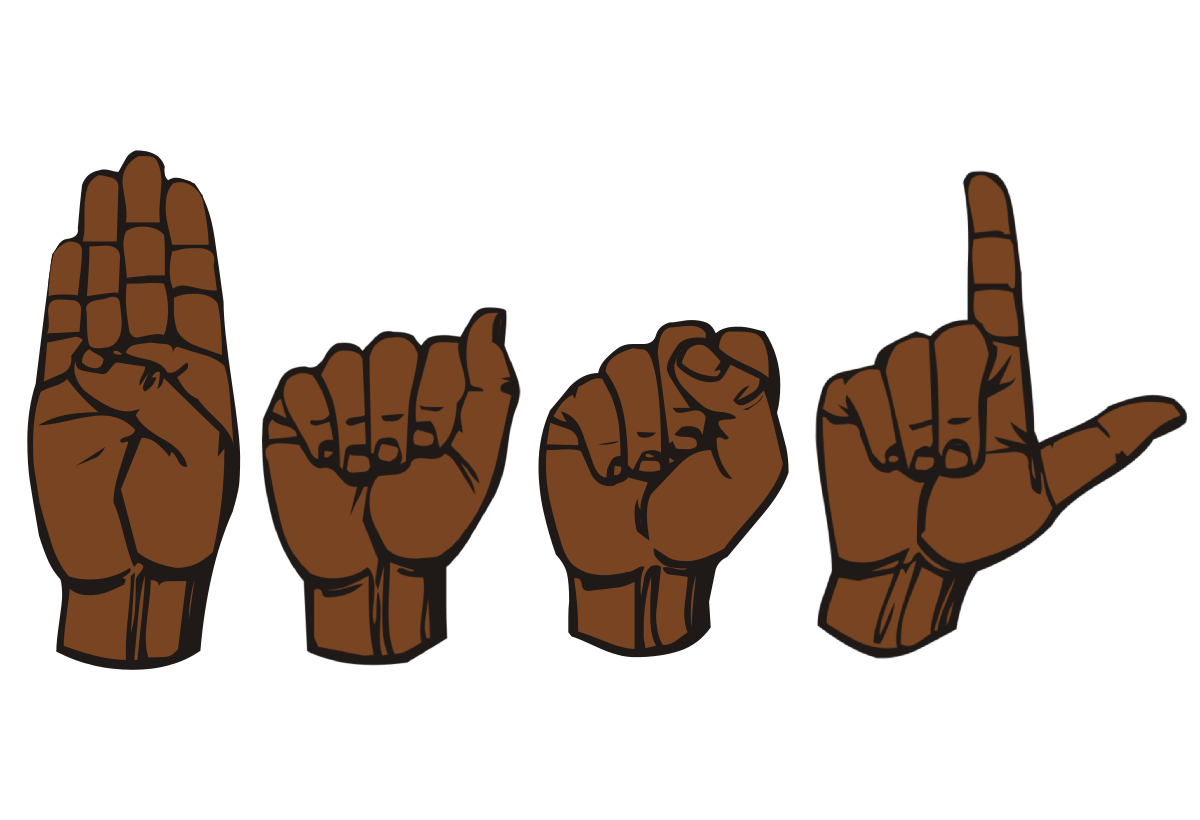

Credit: Nick Dolding/Getty Images

June 7, 2024

The first clinical trial to administer gene therapy to both ears in one person has restored hearing function to 5 children born with a form of inherited deafness, astounding the research team..

Two of the children even gained an ability to appreciate music.

The success of the new approach is detailed in a new study published in Nature Medicine. The work builds on the first phase of the trial, published earlier this year, in which children were treated in a single ear.

“The results from these studies are astounding,” says study co-senior author Zheng-Yi Chen, an associate scientist in the Eaton-Peabody Laboratories at Massachusetts Eye and Ear in the US.

“We continue to see the hearing ability of treated children dramatically progress and the new study shows added benefits of the gene therapy when administrated to both ears, including the ability for sound source localisation and improvements in speech recognition in noisy environments.”

Lead author Yilai Shu, an attending doctor in otolaryngology and an investigator at Eye and Ear, Nose, Throat hospital of Fudan University, China, says: “restoring hearing in both ears of children who are born deaf can maximise the benefits of hearing recovery.

“These new results show this approach holds great promise and warrants larger international trials.”

The children involved in the study were born with DFNB9, which accounts for between 2 and 8% of hereditary deafness. It is caused by mutations in the OTOF gene which prevent the production of functioning otoferlin protein, which can significantly reduce sound transmission from the inner ear hair cells to hearing nerves.

Through minimally invasive surgery, Shu injected adeno-associated virus (AAV) engineered to carry and deliver functioning copies of the human OTOF transgene, into the children’s inner ears.

All 5 children were observed over a 13 or 26-week period and showed hearing recovery in both ears, with “dramatic” improvements in speech perception and sound localisation.

During follow-up, 36 adverse events were observed, the most common being increased white blood cell counts and increased cholesterol levels. However, there were no dose-limiting toxicity or serious adverse events.

The trial is continuing, and participant are stillbeing monitored.

The authors say their results show that the gene therapy is “feasible, safe, and efficacious”.

"

"