mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

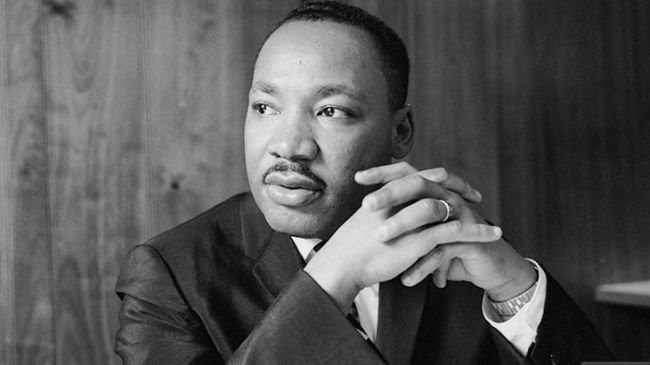

It's a long read, but Dr. Jared Clemons wrote something interesting using Dr. King and A. Phillip Randolph's own words, and how it parallels today:

www.cambridge.org

www.cambridge.org

...

Theoretically, the first objectives of the civil rights movement proper could be achieved without Federal action, if the hearts and minds of 200 million Americans were fully attuned to these objectives. But even if everyone wanted to get rid of unemployment and poverty—and practically everyone does—the specific actions toward these ends cannot be formulated, nor fully executed, by 200 million Americans in their separate and individual capacities. This is what our national union and our Federal Government are for, and we must act accordingly.

—A. Philip Randolph, Freedom Budget for All Americans

Within the white majority there exists a substantial group who cherish democratic principles above privilege and who have demonstrated a will to fight side by side with the Negroes against injustice. Another and more substantial group is composed of those having common needs with the Negro and who will benefit equally with him in the achievement of social progress.

—Martin Luther King, Jr. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

...

Taken together, I argue that through a close reading of King’s and Randolph’s written works and speeches—particularly after the passage of the Voting Rights Act—it is clear that both men understood the limitations of white sympathy, particularly among those who identify as liberal and who might now be aptly described as comprising the professional-managerial class (PMC) (Ehrenreich Reference Ehrenreich1989). Specifically, they lamented that a large segment of white America would not engage in antiracist behavior beyond symbolic gestures to exhibit their sympathy. This acknowledgment was an enormous impetus behind King’s visionary, though marginalized, Poor People’s Campaign. This interracial, grassroots campaign prioritized solidarity with the white poor and working-class rather than the moral resolve of white professionals. Furthermore, Randolph’s Freedom Budget for All Americans was a comprehensive document and clarion call to the Federal government to eradicate Black poverty and, by extension, white poverty.

Building upon King and Randolph’s insights that recognition of shared class interests was a precondition for whites’ participation in substantive antiracist politics—a process that Randolph believe relied upon a strong alliance with organized labor—I consider the ways in which changes in the capitalist order since the time of their writing have constrained white individuals’ political behavior or, more precisely, their antiracist behaviors. More specifically, I evaluate white antiracism under neoliberal capitalism. While Keynesian capitalism—or, more fittingly, the New Deal order—operated under the assumption that the government played a role in providing labor (workers) with a safety net to protect from the market’s excesses, neoliberal capitalism holds that the state has no such obligation; instead, individuals can, through the development of their human capital, become their own safety net (Brown Reference Brown2015). Unsurprisingly, political elites, increasingly committed to the ideological thrust of a percolating neoliberal order, have, for the most part, dismissed the radical demands outlined in Randolph’s Freedom Budget for All Americans and Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign (Le Blanc and Yates Reference Le Blanc and Yates2013). How, then, might the radical demands of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) fare, given that neoliberal capitalism remains hegemonic?Footnote 4

This paper proceeds as follows. First, I provide a brief survey of existing social science research that theorizes the principle-policy gap. The basis of this literature begins with the assumption that whites’ racial attitudes should be predictive of their political behavior. When it is not, this principle-policy gap is often attributed to psychological or sociological forces. I argue, however, that any account of antiracist behavior is incomplete without an analysis of the political-economic circumstances under which individuals operate. Accordingly, I introduce my theory of white antiracism: The privatization of racial responsibility. My theoretical framework considers the conditions under which white individuals’ beliefs in racial egalitarianism—namely white liberals, given that they are likely to harbor such beliefs (as compared to white conservatives)—are likely to predict antiracist behavior, as well as the form this behavior might take.Footnote 5 Given that much of the principle-policy gap research attempts to explain the persistence of racial inequality, particularly in housing and public education, I orient my analysis accordingly. More specifically, given the relentless commodification of both housing and education over the past half-century—coupled with the winnowing of the welfare state and a general undermining of the public good by political elites—education and housing are now viewed as private goods which must be acquired or developed to survive within the neoliberal capitalist order (Brown Reference Brown2015; Eichner Reference Eichner2020). Nevertheless, antiracist concerns have not fallen off the agenda; instead, individuals who express antiracist ideals have been required to consider forms of antiracism that do not inhibit their ability to attain these private goods. As such, I argue that white individuals who harbor antiracist principles will likely engage in antiracist behavior to the extent that it does not impinge upon the attainment of those forms of capital—monetary, human, social, or otherwise—that they perceive as being necessary for survival.

Upon laying out my framework, I also emphasize three conditions that King and Randolph believed were necessary for a successful antiracist project. First, though both men subscribed to the view that any successful movement had to include white Americans, their primary focus was on mobilizing and incorporating poor and working white Americans. For these were individuals with whom a majority of Black people shared a common plight. Neither man, however, downplayed the difficulty of cultivating such a coalition and the potential barrier of white racial prejudice (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010; Randolph, Kersten, and Lucander Reference Randolph, Kersten and Lucander2014). Nevertheless, neither man endorsed the view that white racism was a primordial force, nor did they believe it was immutable. Instead, it was a condition that only political struggle could overcome.

Second, both men had a keen awareness of how "race relations" were, in many ways, a product of the political-economic order and elite governance. In other words, white racism and antiracism alike were products of the material world and the beliefs that individuals hold about the society in which they find themselves. Thus, they believed it was impossible to engage questions of racism or antiracism without grappling with questions of political economy.

Third, and finally, King and Randolph were clear that only the state had the resources and capacity to address the complex problems wrought by capitalism, inter alia joblessness, poverty, access to quality education and housing, segregation, and so forth.Footnote 6 Thus, any successful movement would require getting individuals to recognize their common plight and then directing their needs and concerns upwards at the federal government.

With the framework of the privatization of racial responsibility laid out, I then consider King and Randolph’s insights within the context of our current political moment. In doing so, I argue that elite-driven changes to the political-economic order have made conditions they laid out—solidaristic, interracial politics rooted in material interests and the implementation of state programs to address structural inequalities—difficult to satisfy. Put differently, my theory, the privatization of responsibility, predicts the types of antiracism that white Americans (or, more specifically, white liberal Americans) might engage in, given that King and Randolph’s recommendations have largely gone unheeded.

I conclude by discussing the importance of interracial, class-based politics while also acknowledging the limitations of white racial sympathy, a predominant form of antiracism. Finally, and most importantly, I contend that any successful movement must attack the ideological core of neoliberal capitalism. At the center of this ideological formulation is the notion that the state has no responsibility for securing economic justice—a core demand of the Black Freedom Struggle, past and current—for poor and working people, both Black and others alike.

From “Freedom Now!” to “Black Lives Matter”: Retrieving King and Randolph to Theorize Contemporary White Antiracism | Perspectives on Politics | Cambridge Core

From “Freedom Now!” to “Black Lives Matter”: Retrieving King and Randolph to Theorize Contemporary White Antiracism - Volume 20 Issue 4

Abstract

Many were taken aback by the initial spike in support for Black Lives Matter among white Americans during the summer of 2020. But will these antiracist attitudes translate into antiracist behavior? Accordingly, I ask under what conditions do white Americans engage in antiracist behavior? To answer this question, I build upon the insights of Martin Luther King, Jr., and A. Philip Randolph to theorize contemporary white antiracism. I argue that, under neoliberal capitalism, the conditions they laid out as necessary for the cultivation of productive antiracist politics have been difficult to satisfy. In lieu of that, in many instances, has been the privatization of racial responsibility, which I coin to describe a form of antiracist politics that relies upon white individuals’ sympathetic (and often symbolic) gestures rather than the implementation of more state programs to address structural racial injustices. I discuss what this development might mean for the Black Lives Matter movement—and the Black Freedom Struggle writ large—moving forward....

Theoretically, the first objectives of the civil rights movement proper could be achieved without Federal action, if the hearts and minds of 200 million Americans were fully attuned to these objectives. But even if everyone wanted to get rid of unemployment and poverty—and practically everyone does—the specific actions toward these ends cannot be formulated, nor fully executed, by 200 million Americans in their separate and individual capacities. This is what our national union and our Federal Government are for, and we must act accordingly.

—A. Philip Randolph, Freedom Budget for All Americans

Within the white majority there exists a substantial group who cherish democratic principles above privilege and who have demonstrated a will to fight side by side with the Negroes against injustice. Another and more substantial group is composed of those having common needs with the Negro and who will benefit equally with him in the achievement of social progress.

—Martin Luther King, Jr. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

...

Taken together, I argue that through a close reading of King’s and Randolph’s written works and speeches—particularly after the passage of the Voting Rights Act—it is clear that both men understood the limitations of white sympathy, particularly among those who identify as liberal and who might now be aptly described as comprising the professional-managerial class (PMC) (Ehrenreich Reference Ehrenreich1989). Specifically, they lamented that a large segment of white America would not engage in antiracist behavior beyond symbolic gestures to exhibit their sympathy. This acknowledgment was an enormous impetus behind King’s visionary, though marginalized, Poor People’s Campaign. This interracial, grassroots campaign prioritized solidarity with the white poor and working-class rather than the moral resolve of white professionals. Furthermore, Randolph’s Freedom Budget for All Americans was a comprehensive document and clarion call to the Federal government to eradicate Black poverty and, by extension, white poverty.

Building upon King and Randolph’s insights that recognition of shared class interests was a precondition for whites’ participation in substantive antiracist politics—a process that Randolph believe relied upon a strong alliance with organized labor—I consider the ways in which changes in the capitalist order since the time of their writing have constrained white individuals’ political behavior or, more precisely, their antiracist behaviors. More specifically, I evaluate white antiracism under neoliberal capitalism. While Keynesian capitalism—or, more fittingly, the New Deal order—operated under the assumption that the government played a role in providing labor (workers) with a safety net to protect from the market’s excesses, neoliberal capitalism holds that the state has no such obligation; instead, individuals can, through the development of their human capital, become their own safety net (Brown Reference Brown2015). Unsurprisingly, political elites, increasingly committed to the ideological thrust of a percolating neoliberal order, have, for the most part, dismissed the radical demands outlined in Randolph’s Freedom Budget for All Americans and Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign (Le Blanc and Yates Reference Le Blanc and Yates2013). How, then, might the radical demands of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) fare, given that neoliberal capitalism remains hegemonic?Footnote 4

This paper proceeds as follows. First, I provide a brief survey of existing social science research that theorizes the principle-policy gap. The basis of this literature begins with the assumption that whites’ racial attitudes should be predictive of their political behavior. When it is not, this principle-policy gap is often attributed to psychological or sociological forces. I argue, however, that any account of antiracist behavior is incomplete without an analysis of the political-economic circumstances under which individuals operate. Accordingly, I introduce my theory of white antiracism: The privatization of racial responsibility. My theoretical framework considers the conditions under which white individuals’ beliefs in racial egalitarianism—namely white liberals, given that they are likely to harbor such beliefs (as compared to white conservatives)—are likely to predict antiracist behavior, as well as the form this behavior might take.Footnote 5 Given that much of the principle-policy gap research attempts to explain the persistence of racial inequality, particularly in housing and public education, I orient my analysis accordingly. More specifically, given the relentless commodification of both housing and education over the past half-century—coupled with the winnowing of the welfare state and a general undermining of the public good by political elites—education and housing are now viewed as private goods which must be acquired or developed to survive within the neoliberal capitalist order (Brown Reference Brown2015; Eichner Reference Eichner2020). Nevertheless, antiracist concerns have not fallen off the agenda; instead, individuals who express antiracist ideals have been required to consider forms of antiracism that do not inhibit their ability to attain these private goods. As such, I argue that white individuals who harbor antiracist principles will likely engage in antiracist behavior to the extent that it does not impinge upon the attainment of those forms of capital—monetary, human, social, or otherwise—that they perceive as being necessary for survival.

Upon laying out my framework, I also emphasize three conditions that King and Randolph believed were necessary for a successful antiracist project. First, though both men subscribed to the view that any successful movement had to include white Americans, their primary focus was on mobilizing and incorporating poor and working white Americans. For these were individuals with whom a majority of Black people shared a common plight. Neither man, however, downplayed the difficulty of cultivating such a coalition and the potential barrier of white racial prejudice (King, King, and Harding Reference King, King and Harding2010; Randolph, Kersten, and Lucander Reference Randolph, Kersten and Lucander2014). Nevertheless, neither man endorsed the view that white racism was a primordial force, nor did they believe it was immutable. Instead, it was a condition that only political struggle could overcome.

Second, both men had a keen awareness of how "race relations" were, in many ways, a product of the political-economic order and elite governance. In other words, white racism and antiracism alike were products of the material world and the beliefs that individuals hold about the society in which they find themselves. Thus, they believed it was impossible to engage questions of racism or antiracism without grappling with questions of political economy.

Third, and finally, King and Randolph were clear that only the state had the resources and capacity to address the complex problems wrought by capitalism, inter alia joblessness, poverty, access to quality education and housing, segregation, and so forth.Footnote 6 Thus, any successful movement would require getting individuals to recognize their common plight and then directing their needs and concerns upwards at the federal government.

With the framework of the privatization of racial responsibility laid out, I then consider King and Randolph’s insights within the context of our current political moment. In doing so, I argue that elite-driven changes to the political-economic order have made conditions they laid out—solidaristic, interracial politics rooted in material interests and the implementation of state programs to address structural inequalities—difficult to satisfy. Put differently, my theory, the privatization of responsibility, predicts the types of antiracism that white Americans (or, more specifically, white liberal Americans) might engage in, given that King and Randolph’s recommendations have largely gone unheeded.

I conclude by discussing the importance of interracial, class-based politics while also acknowledging the limitations of white racial sympathy, a predominant form of antiracism. Finally, and most importantly, I contend that any successful movement must attack the ideological core of neoliberal capitalism. At the center of this ideological formulation is the notion that the state has no responsibility for securing economic justice—a core demand of the Black Freedom Struggle, past and current—for poor and working people, both Black and others alike.

Last edited: