MischievousMonkey

Gor bu dëgër

I've wanted to read it for a long time, and finally received it.

Aside note: I'm thinking on doing, in the Root section, some review threads on different pieces that are not often discussed like that on the internet mainly because of accessibility (for example, most of the historical resources on West Africa being available only in French, such as:

Nigritia Relations, Including an exact description of its kingdoms and its governments, the religion, the mores, customs & rarities of this country. With the discovery of the Senega river, of which a particular map was made - Jean Baptiste Gaby, 1689

(Nigritia meaning literally "The country of Negroes")

Or

About the cult of fetish gods, or, parallel of the ancient religion of Egypt with the actual religion of Nigritia - Charles de Brosses, 1760

(Nigritia meaning literally "The country of Negroes")

Or

About the cult of fetish gods, or, parallel of the ancient religion of Egypt with the actual religion of Nigritia - Charles de Brosses, 1760

--x--

Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies

First words of the book's introduction

Between the early 1500s and the late 1860s, an estimated twelve million African men, women, and children were forcibly transported across the Atlantic Ocean.1 About seven million were displaced through the Sahara desert and the Indian Ocean, in a movement that started in the seventh century and lasted until the twentieth.2 If the idea that the deported Africans walked quietly into servitude has lost ground in some intellectual circles, it is still going strong in popular culture; as are the supposed passivity or complicity of the rest of their compatriots and their lack of remorse for having allowed or participated in this massive displacement. In recent years, a few works have investigated the feeling of guilt apparent in some tales and practices linked to the Atlantic slave trade, but the Africans’ actions during these times, except in their dimension of collaboration, have hardly been explored (Iroko 1988; Austen 1993; Shaw 2002).

This collection of essays seeks to offer a more balanced perspective by exploring the various strategies devised by the African populations against the slave trade. It is centered on the Atlantic trade, but some chapters cover strategies against the trans-Saharan and domestic displacement of captives, and these analyses suggest that strategies against the slave trade were similar, irrespective of the slaves’ destination.3 The book focuses on a single area, West Africa, in order to provide a sense of the range of strategies devised by the people to attack, defend, and protect themselves from the slave trade. This evidences the fact that they used various defensive, offensive, and protective mechanisms cumulatively. It also highlights how the contradictions between the interest of individuals, families, social orders, and communities played a part in feeding the trade, even as people fought against it. Therefore, this book is not specifically about resistance, which is arguably the most understudied area of slave trade studies—with only a few articles devoted to the topic (see Wax 1966; Rathbone 1986; McGowan 1990; Inikori 1996). Resistance to capture and deportation was an integral part of the Africans’ actions, but their strategies against the slave trade did not necessarily translate into acts of resistance. Indeed, some mechanisms were grounded in the manipulation of the trade for the protection of oneself or one’s group. The exchange of two captives for the freedom of one or the sale of people to acquire weapons were strategies intended to protect specific individuals, groups, and states from the slave trade. They were not an attack against it; still, they were directed against its very effects. Some strategies may thus appear more accommodation than resistance. Yet they should be envisioned in a larger context. Strategic accommodation does not mean that people who had redeemed a relative by giving two slaves in exchange were not at some other point involved in burning down a factory; or that the guns acquired through the sale of abductees were not turned directly against the trade. Resistance, accommodation, participation in the trade and attacks against it were often intimately linked.

But what precisely did people do to prevent themselves and their communities from being swept away to distant lands? What mechanisms did they adopt to limit the impact of the slave-dealing activities of traders, soldiers, and kidnappers? What environmental, physical, cultural, and spiritual weapons did they use? What short- and long-term strategies did they put in place? How did their actions and reactions shape their present and future? What political and social systems did they design to counteract the devastation brought about by the slave trade?

These are questions the literature has not adequately addressed. A large part of the studies on the Atlantic slave trade have focused instead on its economics: volume, prices, supply, cargo, expenses, profitability, gains, losses, competition, and partnerships. Because the records of shippers, merchants, banks, and insurance companies provide the most extensive evidence, economic and statistical studies are disproportionately represented in slave trade studies. But a great number, if not most, envision the Africans almost exclusively as trading partners on the one hand and cargo on the other. Viewed from another perspective, research based entirely or primarily on slavers’ log books and companies’ records are almost akin to studying the Holocaust in terms of expenses incurred during the transportation of the “cargo,” pro¤ts generated by free labor, quantity and cost of gas for the death chambers, size and efficiency of the crematoria, and overall operating costs of the death camps. In the difference in historical treatment between the Holocaust and the slave trade, words may play a larger role than readily perceived.

If the word Holocaust is a fitting and immediately understood description of the crime against humanity that it was, the expression slave trade, by contrast, tends to let the collective consciousness equate this crime with a business venture. Naturally, genocide and other crimes against humankind are not commercial enterprises but, one may argue, the slave trade was only partially so. The demand for free labor in the Americas resulted in the purchase, kidnapping, and shipment of Africans by Westerners who entered into commercial relations with African traders and rulers. The violent seizure of people, however, did not entail any transaction; the affected African communities were not involved in business deals. Although important to our understanding of the events, the literature that focuses on the commercial part of the process does not capture the experience of the vast majority of the affected Africans. It is no stretch to assume that the tens of millions who suffered, directly and indirectly, from this immense disaster were primarily concerned with elaborating strategies to counter its consequences on themselves, their loved ones, and their communities.

Violence was an intrinsic—but not exclusive—component of these strategies, whether on the part of the direct victims or of the larger population. If nothing else, the need for shackles, guns, ropes, chains, iron balls, whips, and cannons—that sustained a veritable European Union of slave trade–related jobs—eloquently tells a story of opposition from the hinterland to the high seas. As explained by a slave trader, “For the security and safekeeping of the slaves on board or on shore in the African barrac00ns, chains, leg irons, handcuffs, and strong houses are used. I would remark that this also is one of the forcible necessities resorted to for the preservation of the order, and as recourse against the dangerous consequences of this traffic” (Conneau 1976). Western slavers were indeed cautious when taking people by force out of Africa. Wherever possible, as in Saint-Louis and Gorée (Senegal), James (Gambia), and Bance (Sierra Leone), slave factories were located on islands to render escapes and attacks difficult. In some areas, such as Guinea-Bissau, the level of distrust and hostility was so high that as soon as people approached the boats “the crew is ordered to take up arms, the cannons are aimed, and the fuses are lighted. . . . One must, without any hesitation, shoot at them and not spare them. The loss of the vessel and the life of the crew are at stake” (Durand 1805, 1:191).4 Violence was particularly evident throughout the eighteenth century—the height of the slave trade—when numerous revolts directly linked to it broke out in Senegambia.5 Fort SaintJoseph, on the Senegal River, was attacked and all commerce was interrupted for xii Introduction six years (Durand 1805, 2:273). Several conspiracies and actual revolts by captives erupted on Gorée Island and resulted in the death of the governor and several soldiers. In addition, the crews of several slave ships were “cut off” (killed) in the Gambia River (Pruneau de Pommegorge 1789, 102–3; Hall 1992, 90– 93; Guèye 1997, 32–35; Thilmans 1997, 110–19; Eltis 2000, 147). In Sierra Leone people sacked the captives’ quarters of the infamous trader John Ormond (Durand 1807, 1:262).6 The level of fortification of the forts and barrac00ns attests to the Europeans’ distrust and apprehension. They had to protect themselves, as Jean-Baptiste Durand of the Compagnie du Sénégal explained, “from the foreign vessels and from the Negroes living in the country” (263). Written records of the attack of sixty-one ships by land-based Africans—as opposed to the captives on board—have already been found for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Eltis 2000, 171).

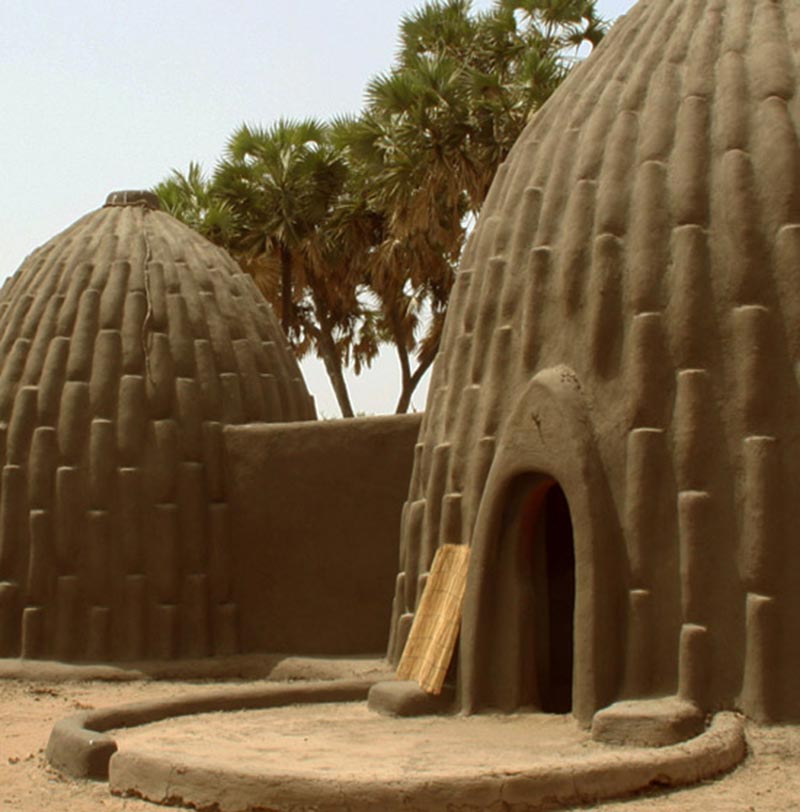

The acts—or fear—of armed struggle may have seemed the most dreadful to the Europeans, but the Africans’ struggle encompassed more than a physical fight. It was based on strategies in which not only men who could bear arms, but women, children, the elderly, entire families, and communities had a role. As exemplified in the following chapters, to protect and defend themselves and their communities and to cripple the international slave trade that threatened their lives, people devised long-term mechanisms, such as resettling to hard-to-find places, building fortresses, evolving new—often more rigid—styles of leadership, and transforming the habitat and the manner in which they occupied the land. As a more immediate response, secret societies, women’s organizations, and young men’s militia redirected their activities toward the protection and defense of their communities. Children turned into sentinels, venomous plants and insects were transformed into allies, and those who possessed the knowledge created spiritual protections for individuals and communities. In the short term, resources were pooled to redeem those who had been captured and were held in factories along the coast. At the same time, in a vicious circle, raiding and kidnapping became more prevalent as some communities, individuals, and states traded people to access guns and iron to forge better weapons to protect themselves, or in order to obtain in exchange the freedom of their loved ones. As an immediate as well as a long-term strategy, some free people attacked slave ships and burned down factories. And when everything else had failed, a number of men and women revolted in the barrac00ns and aboard the ships that transported them to the Americas, while others jumped overboard or let themselves starve to death.

People adopted the defensive, protective, and offensive strategies that Introduction xiii worked for them, depending on a variety of factors and the knowledge they possessed. Although a culture of “virile violence” tends to place armed struggle at the top of the pyramid, it is rather futile to rate those strategies. They worked or not, depending on the circumstances, not on intrinsic merit, and they each responded to specific needs. Some people may have elected to attack the slave ships first and then resettle in hard-to-find places as circumstances changed. Others may have relocated as a first option. And, naturally, because the conditions could not have existed at the time, Africans did not use other mechanisms that contemporary hindsight believes would have been more efficient.

[...]

[WORK IN PROGRESS]

.

.