You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Facebook bans news posting in Australia (Update: FB falls back)

- Thread starter FAH1223

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?*doesn't use facebook or any social media* what did facebook do wrong? they didn't cut a deal with rupert so they said fukk all media links? is cutting a deal with rupert ever a good thing?

*doesn't use facebook or any social media* what did facebook do wrong? they didn't cut a deal with rupert so they said fukk all media links? is cutting a deal with rupert ever a good thing?

pay for linking? are they using the word linking in a different sense than hyperlinking and instead mean posting their articles on your platform (basically stealing someone's content)? if it's just hyperlinking facebook should tell them to fukk off. they are sending you traffic. if you can't monetize that traffic then don't make your site accessible via 3rd party links.

Wonder if their will be the straw that leads to regulation.

Facebook is 'schoolyard bully' in Australia news row, says UK media boss

Facebook’s move to block all media content in Australia shows why countries need robust regulation to stop tech firms behaving like a “schoolyard bully”, the head of the UK’s news media trade group has said.

Henry Faure Walker, the chair of the News Media Association, said Facebook’s ban during a pandemic was “a classic example of a monopoly power being the schoolyard bully, trying to protect its dominant position with scant regard for the citizens and customers it supposedly serves”.

Australians have been blocked from viewing or sharing news on the social network in an escalation of a row over whether Facebook should have to pay media companies for displaying their content.

Facebook is opposed to the federal government’s news media code, which will require it and Google to reach commercial deals with news outlets whose links drive traffic to their platforms, or be subjected to forced arbitration to agree a price. Google and Facebook have said the code unfairly penalises their platforms.

The legislation, which the government says is aimed at “levelling the playing field” between the tech firms and struggling publishers, is expected to be passed by the Australian parliament within days, prompting Google to agree preemptive deals with several outlets in recent days.

Overnight on Wednesday Facebook – which is used by 18 million Australians – prevented the sharing of news and wiped clean the pages of media companies, including the public broadcaster’s television, radio and non-news pages. Government pages – including on bushfires, mental health, emergency services and even meteorology – were also blocked, as were community, women’s health and domestic violence support pages.

Faure Walker said: “Facebook’s actions in Australia demonstrate precisely why we need jurisdictions across the globe, including the UK, to coordinate to deliver robust regulation to create a truly level playing between the tech giants and news publishers.”

Julian Knight, the chair of the British parliament’s digital, culture, media and sport committee, echoed Faure Walker when he told Reuters: “This action – this bullyboy action – that they’ve undertaken in Australia will I think ignite a desire to go further amongst legislators around the world.

“We represent people and I’m sorry but you can’t run bulldozer over that – and if Facebook thinks it’ll do that it will face the same long-term ire as the likes of big oil and tobacco.”

Guardian Media Group, which owns the Guardian and the Observer, said Facebook’s action cleared the way for the spread of misinformation at a time when facts and clarity are sorely needed.

“We believe that public interest journalism should be as widely available as possible in order to have a healthy functioning democracy,” a spokesman said. “We have consistently argued that governments must play a role when it comes to establishing fair and transparent regulation of online platforms.”

Hours before Facebook’s move, Google and Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp signed a multi-year partnership that will lead to the search engine paying for journalism from news sites around the world including the Wall Street Journal, the Times and the Australian.

Australia’s prime minister, Scott Morrison, said on Thursday that Facebook’s show of strength would “confirm the concerns that an increasing number of countries are expressing about the behaviour of big tech companies who think they are bigger than governments and that the rules should not apply to them”.

He wrote on Facebook:“Facebook’s actions to unfriend Australia today, cutting off essential information services on health and emergency services, were as arrogant as they were disappointing. They may be changing the world, but that doesn’t mean they run it.”

The federal treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, said the ban confirmed the “immense market power of these media digital giants. These digital giants loom very, very large in our economy and on the digital landscape. The Morrison government remains absolutely committed to legislating and implementing the code.”

Tim O’Connor from Amnesty International Australia said it was “extremely concerning” that a private company was willing to control access to information on which people rely. “Facebook’s action starkly demonstrates why allowing one company to exert such dominant power over our information ecosystem threatens human rights,” O’Connor said.

Elaine Pearson, the Australia director at Human Rights Watch Australia, said it was a “dangerous turn of events. Cutting off access to vital information to an entire country in the dead of the night is unconscionable.”

Facebook blamed the Australian government’s definition of news content in the media bargaining code for the “inadvertent” blanket ban on government pages – an interpretation the government rejects.

“Government pages should not be impacted by today’s announcement,” a Facebook spokesperson said. The company said it would reverse the ban on those pages, and by midday on Thursday some pages had been restored, including those run by the Bureau of Meteorology and the state health departments.

Facebook argues that the British media market is different, after it launched Facebook News through partnerships with publishers such as the Daily Mail group, the Financial Times, the Guardian and the Telegraph.

EU countries do not face the same situation as Australia because of new copyright rules that protect publishers in Europe, the bloc’s executive has said.

Unfriend whole countries brehs.

AnonymityX1000

Veteran

MIKE SPLEAN

Superstar

Eh

88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

need to read more about the law kinda mixed views on the tweets

Obviously I think citizens need more rights and protections, that platforms need to be regulated further and or broken up and bots and fake news need to be addressed...

Obviously I think citizens need more rights and protections, that platforms need to be regulated further and or broken up and bots and fake news need to be addressed...

I can understand data sharing, but the whole "pay per link" thing is BS, and FB should push back. Murdoch is trying to use government to shake down FB. fukk that.

I can understand data sharing, but the whole "pay per link" thing is BS, and FB should push back. Murdoch is trying to use government to shake down FB. fukk that.

Did you read this part?

An Unstoppable Force Meets an Australian Object

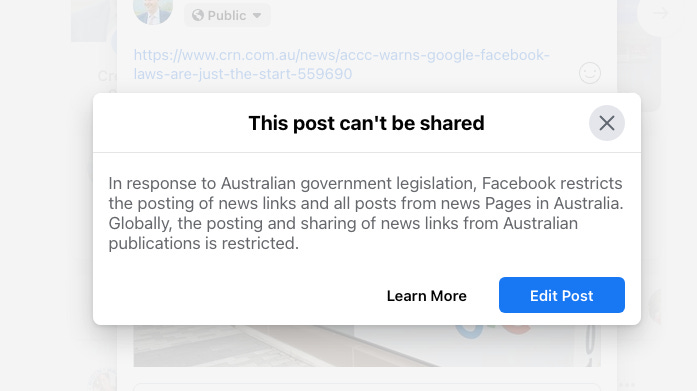

Facebook stopped allowing the sharing of news in Australia, after the government put forward a law requiring the firm to negotiate with news publishers over the terms of content distribution. The firm also stopped letting Australian publishers be shared anywhere in the world on Facebook. Facebook also did their usual ‘move fast and break things,’ accidentally censoring much of the South Pacific, but the result is that when you try to post Australian news, this is the message you get.

There’s a lot of noise about this law, as one might expect. Pro-Facebook libertarians are saying it’s a “link tax” written by Luddites, and some prominent fancy people are even saying it will break the internet, while news publishers are saying it’s about time for this kind of law. This law does matters, because unlike Europe’s constant noisy pretend attempts to address big tech, this is the first time we’re really seeing a nation actually attempt to force the platforms do something they don’t want to do. And fortunately, we don’t have to trust any of these people in the debate, and we can read the law itself, or read the explanatory document the Australian legislature provides to explain it.

As longtime readers know, I’ve been paying close attention to Australia’s antitrust policies for years, because the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission head Rod Sims has been on the leading edge of investigating the privacy, data practices, and market power of big tech platforms. This law comes out of the Digital Markets Inquiry launched in 2017; it is one of the first recommendations by the ACCC on addressing big tech, but it certainly isn’t the last one. (Here, for instance, is the ACCC’s groundbreaking report on the complex adtech supply chain released late last month, which built on the Texas AG antitrust case against Google. We can expect Australia to lead in this realm as well.)

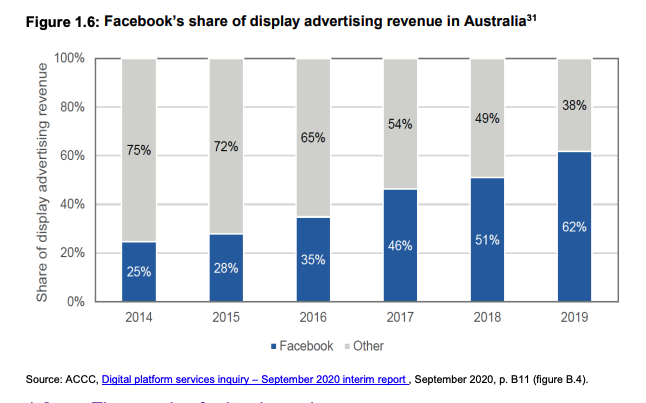

The law is designed to target a specific problem, which is the death of newspapers resulting from the monopolization of the Australian advertising market. Australia has lost 15% of its newspapers since 2008, and dozens of small cities now have no newspaper coverage. This graph from the ACCC digital platform inquiry shows part of the monopoly problem driving the collapse.

What Does This Australian Law Do?

The law says that if you are a dominant digital platform, then you have an obligation to engage in good faith bargaining with news outlets whose content you distribute over the terms of that distribution. The law only applies if there is a bargaining imbalance with media outlets. So this isn’t a tax, it is an anti-monopoly law.

Much of the bill has to do with designating who gets to be a news publisher. The bill says pure opinion stuff doesn't count, and neither does pure sports and entertainment. Media outlets have to register with the government to get bargaining rights. The bill mandates that digital platforms tell media outlets in advance what data they collect and when they are going to change important algorithms on which those outlets rely, like if they are going to change referral traffic in a way that would eliminate more than 20% of the audience and revenue. That’s totally reasonable, basically saying Facebook has to give you two weeks notice if it is going to destroy your business.

The law also has non-discrimination and anti-retaliation provisions, to make sure that dominant digital platforms don’t use fear to bully publishers. Platforms have to treat non-news entities like news entities in how they distribute content, and they can’t retaliate if a news entity chooses to register and demand bargaining rights.

Once you are a news outlet, you get certain rights. Platforms have to tell news outlets about the data they collect - they don't have to share the data, but they have to explain what they are collecting. And during bargaining, parties have to give information to one another showing how they make money, so there’s no opaque hiding of how one uses data to profit. This is a transparency measure to force big tech to show how they price and allocate advertising (which is something Facebook constantly seems to be using to defraud advertisers.)

News outlets and platforms can negotiate however they want, for a short period of time. The platform can pay based on traffic or simply cover a percentage of news gathering costs. But only, and this is the key point, if there is a bargaining imbalance, aka if the platform is taking all the ad revenue. If a digital platform doesn’t have bargaining power against media outlets, aka it’s not dominant, then there is no requirement for any sort of negotiations.

What happens if negotiations fail? If a dominant digital platform and media outlet can't reach a deal, then an arbitrator steps in. The arbitrator must consider the the value that both the platform and news outlet provide, as well as the bargaining imbalance between them, meaning that if, as Facebook claims, media outlets offer zero value to platforms, then it can simply prove this in arbitration and pay nothing. The arbitrator doesn’t micro-manage the process, but does ‘baseball style’ arbitration, meaning both sides give an offer, and the arbitrator picks one of them. This kind of arbitration is both faster and less intrusive that standard government regulation, and creates the incentive for both sides to offer non-extreme proposals they can live with, for fear the arbitrator will simply pick the other side if they suggest something outlandish.

The idea behind the law is to mimic a healthy market, where there is transparency of data and a robust set of buyers and sellers instead of a few dominant platforms. As the legislature notes, "This allows the panel, in making their determination, to consider the outcome of a hypothetical scenario where commercial negotiations take place in the absence of the bargaining power imbalance." A better solution would be to create a real market, to break up these firms, like Newscorp recommended and the ACCC rejected (so much for Murdoch bogeyman). But Australia rejected that approach, probably because it’s a small country without the leverage to force a break-up.

This law wouldn’t work as written in America, because we wouldn’t want publishers to register with the government, but it’s a fairly reasonable conceptualization of how to organize an anti-monopoly provision in a small country without the ability to break up the foreign tech behemoths its citizens use.

In other words, despite what Facebook’s PR armies are saying, it isn’t a link tax, it is an anti-monopoly law that Facebook is opposing because the law will undermine the firm’s ability to monopolize the ad market and force transparency in how the firm gathers and manages its vast data horde. In some ways, it is an existential threat to the company (which I think might be hiding some things about its business model, considering its revenue is growing at 20-30% a year even though its user base in the U.S. and Europe where it makes most of its money is flat).

Facebook’s response to this law was to flex some serious muscles, and block the sharing of news in Australia on its platform. Doing so was a disaster, at least PR-wise, because it revealed how much power Facebook really has. The social media monopolist lost credibility globally, with Canadian and UK politicians attacking the firm as a bad faith actor. Facebook even lost American support; as late as last month, the United States Trade Representative was supporting the company against Australia’s law, but the American government seems to have switched course, and is now neutral. It’s now only a matter of time before Facebook is broken up and regulated.

The details of this law are interesting, but the real point of what Australia is doing is to that it is asserting the rule of law against a monopolist. In response, Facebook is saying, we are more powerful than your democratic officials.