Doobie Doo

Veteran

The Superman Crossover That Perfectly Explained White Privilege Decades Ago

Evan Narcisse

Yesterday 1:15pm

Filed to: ICON

72.0K

206108

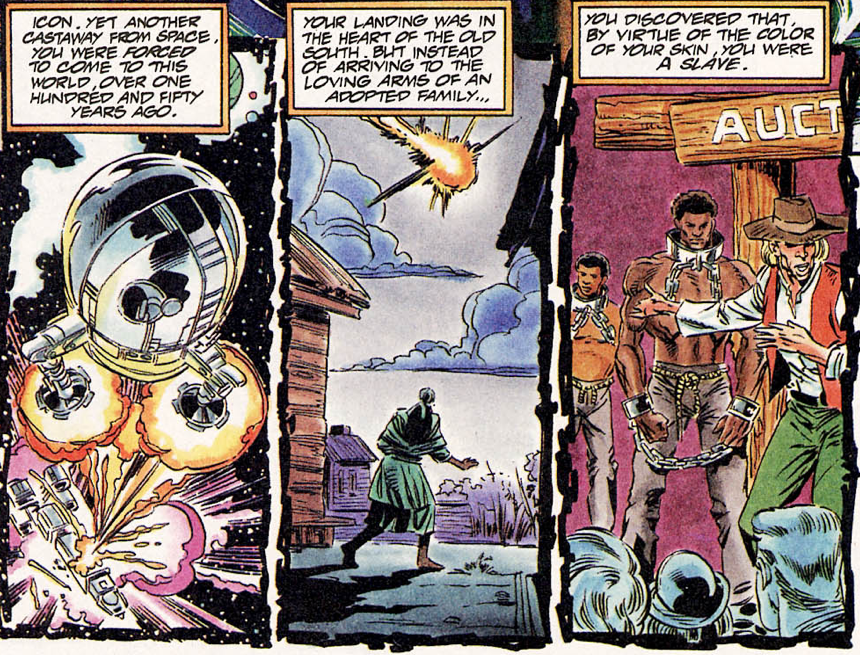

An alien ship lands on Earth. Its occupant gets raised as human, hiding special abilities for fear of reprisal. But when the superpowered extraterrestrial becomes an adult, Truth, Justice and the American Way mean something very different. Because this strange visitor from another planet is black.

In 1993, a company called Milestone Media released a slate of comic-book series set in a multicultural universe where most of the heroes were black. With the exception of magazine editor Derek T. Dingle, Milestone’s founders—Christopher Priest, Michael Davis, Denys Cowan and Dwayne McDuffie—were all comics industry veterans who’d worked at Marvel and DC. Their collective desire to broaden the horizons of the medium’s characters and readership led them to come together and form Milestone. In the work that followed—published and distributed by DC Comics—the good guys and bad guys who battled in the in a fictional midwestern city called Dakota came from a multitude of ethnicities and walks of life. Characters in titles like Blood Syndicate, Heroes, and Deathwish were trailblazing efforts to conceptualize superheroes who were vessels for gender fluidity, loving same-sex relationships and socioeconomic tension. The subtext was never so heavy-handed as to take away from the well-crafted superhero yarns.

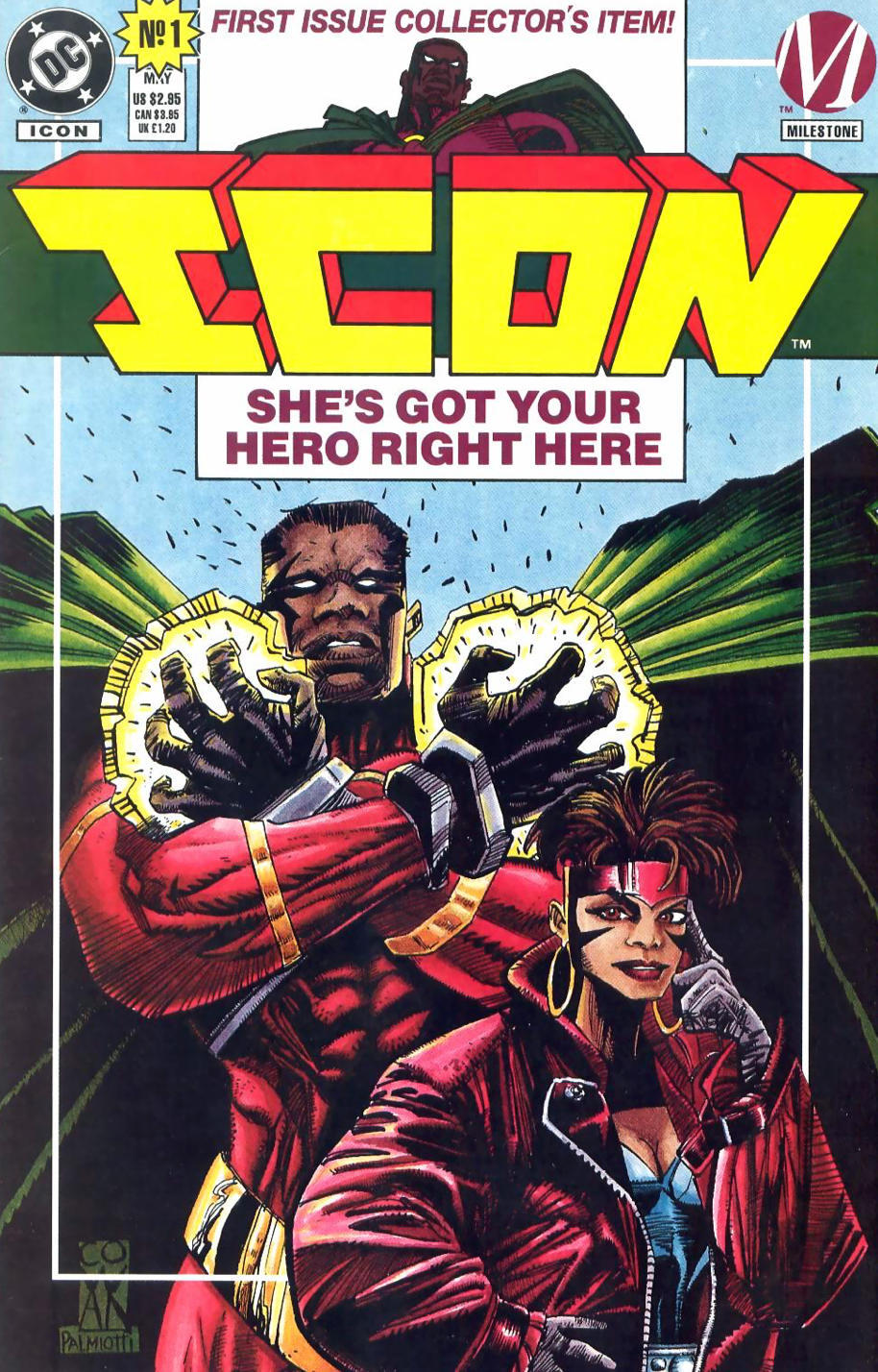

One of the first books that Milestone put out into the world was Icon, featuring a superstrong, cape-wearing flying hero with a young sidekick named Rocket. The series’ first issue introduces Icon’s secret identity of Augustus Freeman, a politically conservative African-American lawyer who’s been alive for more than 150 years.

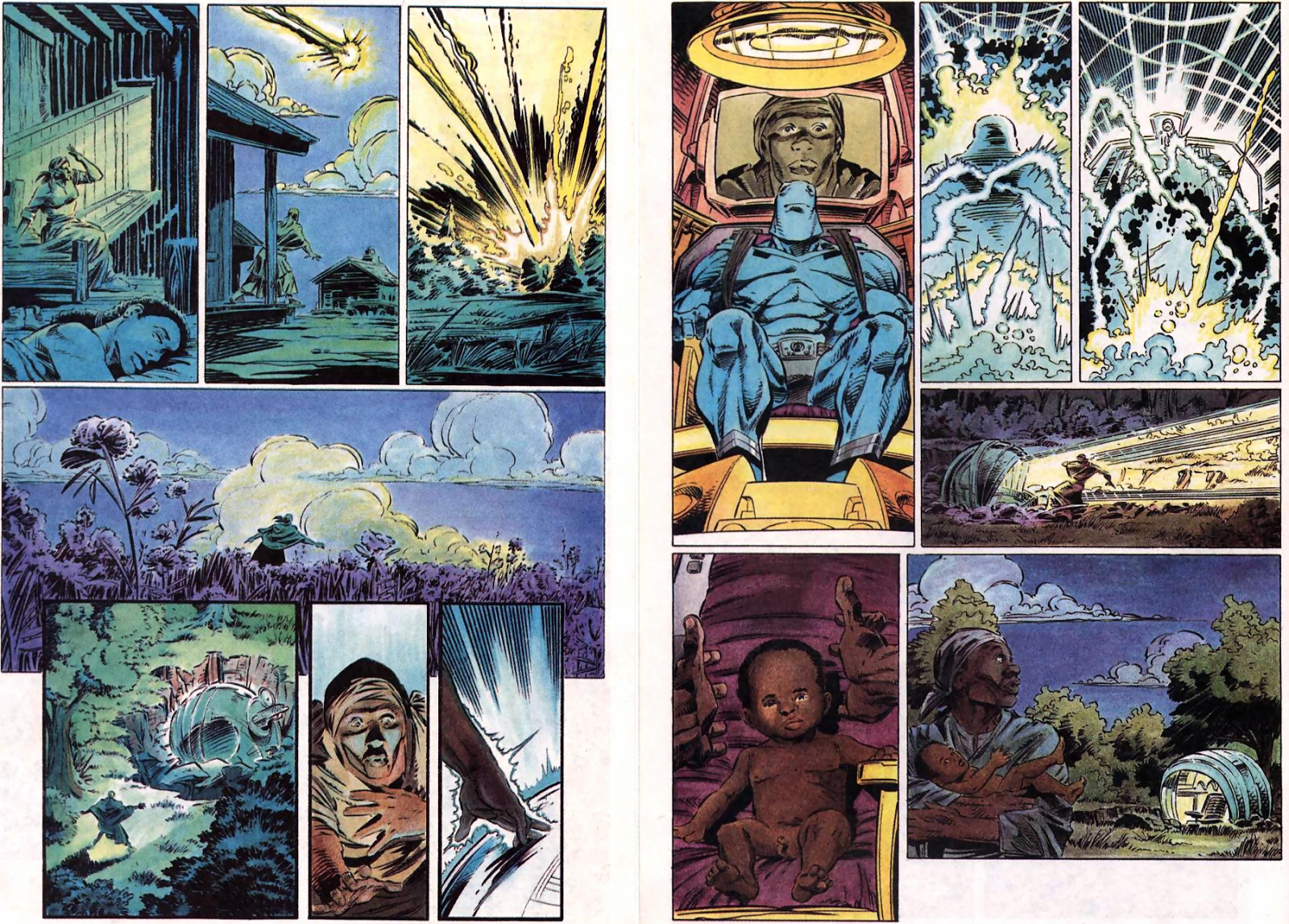

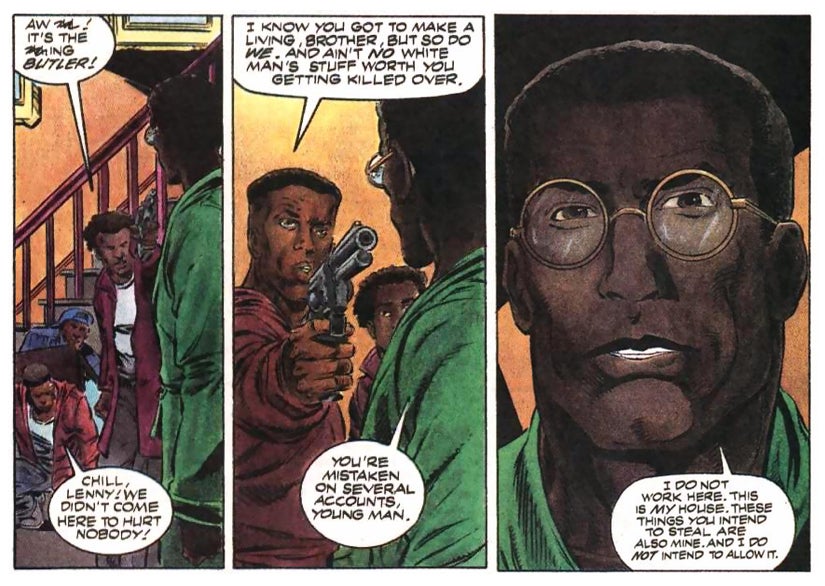

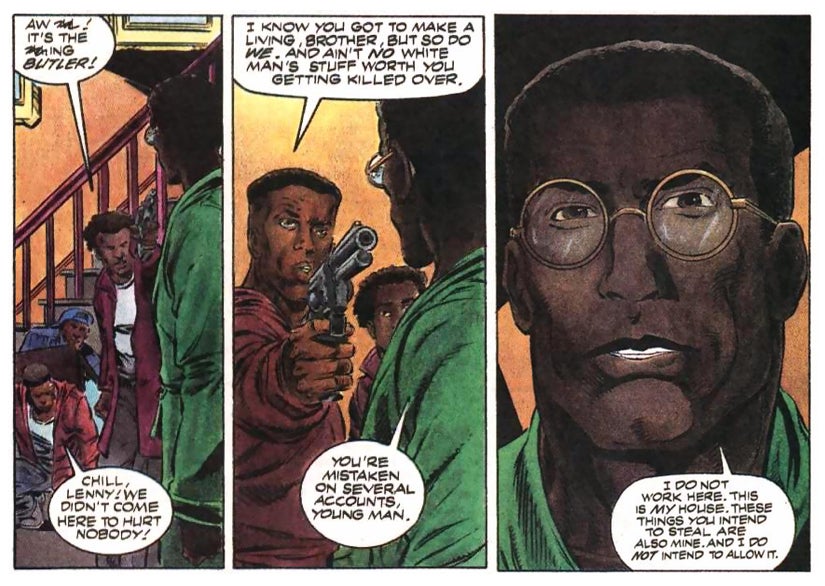

Freeman is really an alien; he assumed human traits because his alien escape pod landed in the Deep South in 1839 and imprinted on the DNA of the field slave who became his adopted mother. If you need a modern-day reference for Augustus’ politics, think of someone like Herman Cain or Ben Carson. His bubble of complacency gets burst by a home invasion robbery, which he uses superhuman abilities to stop.

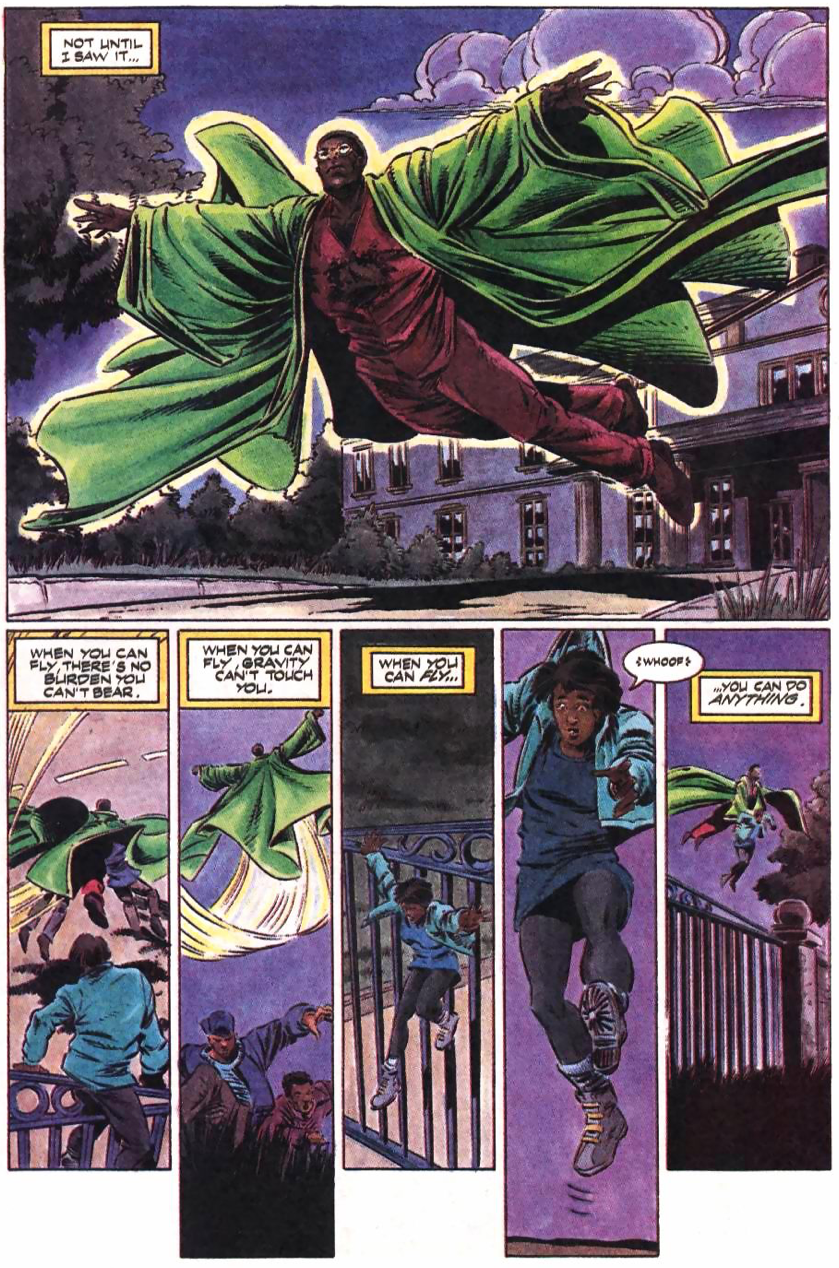

Raquel Ervin is one of the teens who tried to rob Freeman and, weeks after seeing him take to the sky, the Toni Morrison-wannabe decides that Augustus is going to be a superhero and she’s going to be his sidekick.

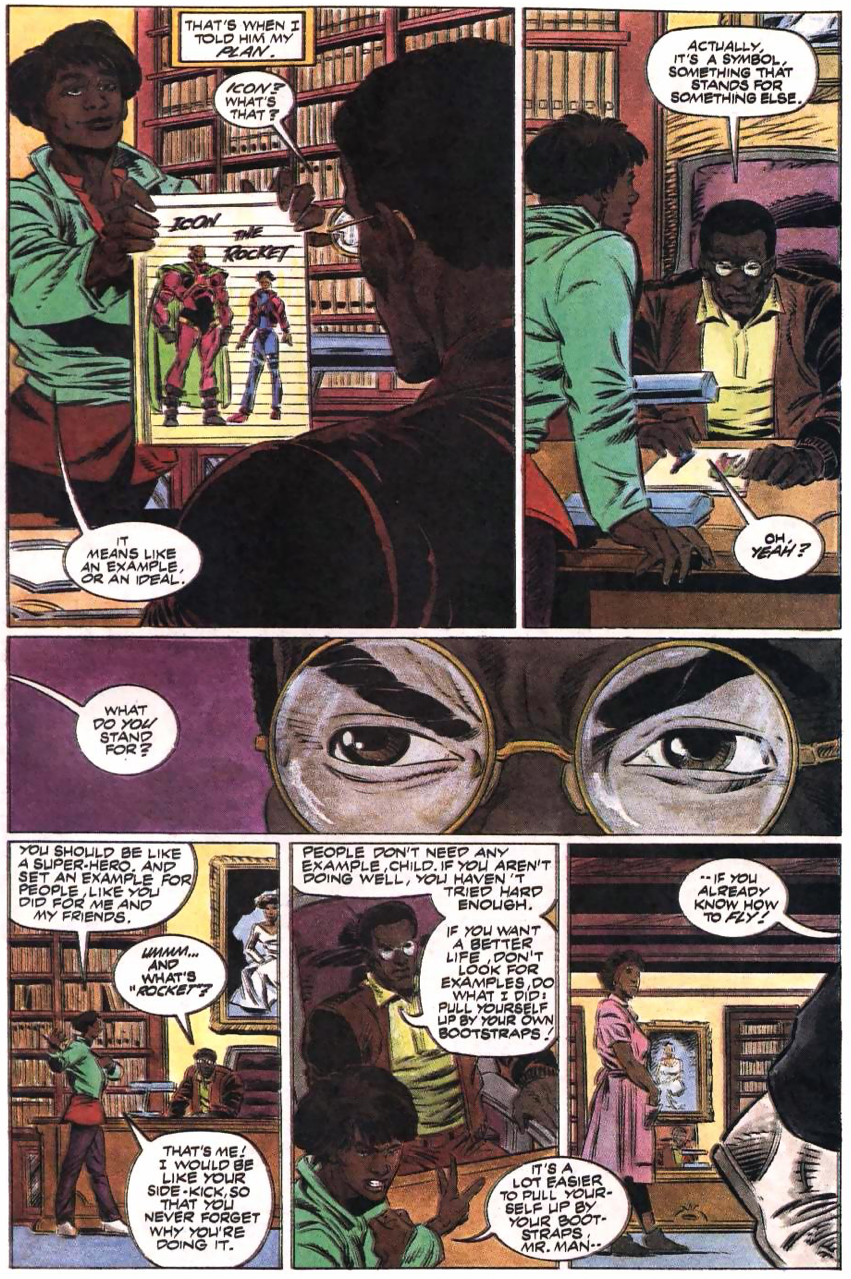

Co-created and written by McDuffie with art by M.D. “Doc” Bright, Iconrepresented an intentional shift from how the black heroes of previous decades were presented. Augustus Freeman wasn’t “street” and didn’t traffic in the jivey slang that characterized Luke Cage and other inner-city crimefighters.Icon #1 established one of the ongoing themes that series would touch, an exploration of what individuals and society owe each other. Raquel’s low-income realities don’t afford her the resources to make her dreams of becoming a writer come true while Augustus realizes that his upper-class elitism has cut him off from the world around him. He’s so out of touch that he thinks he can just fly down and offer his help to the cops dealing with a hostage situation.

He is, of course, very wrong.

I was in college when the Milestone line debuted, gobsmacked by the idea that there was going to be a whole universe of non-white superheroes. My excitement led me to do a project on the imprint for a cultural journalism class taught by the late, trailblazing pop music critic Ellen Willis. I remember a dismissive classmate sniffing at Icon, saying “So, he’s basically like a black Superman, then?” I didn’t always speak up a lot in college, the confidence that I have now in my faculties was still a long time coming. (I’m forever haunted by an a$$hole TA in a PoliSci class who ranted that “crack was a black drug” because it was years before I realized I could’ve retorted by asking him how crack got to the inner cities.) But when that classmate made his shallow remark about Icon, I said “No, he’s not a black Superman. And the book is about exactly why he can’t be.” I didn’t know I could say something like that until I actually said it. Something was waking up in me.

The late, legendary Dwayne McDuffie knew the possibilities of superhero comics. At their best, they can portray humanity in all its messy fullness, so that when our loftiest ideals win out over our worst aspects we’d feel that much closer to the heroes we read about. Augustus is uptight and judgmental, sheltered by his success. His turn towards understanding the generations that came after him is a journey back to empathy and community. He’s a Superman analog who isn’t already perfect; he’s perfecting himself.

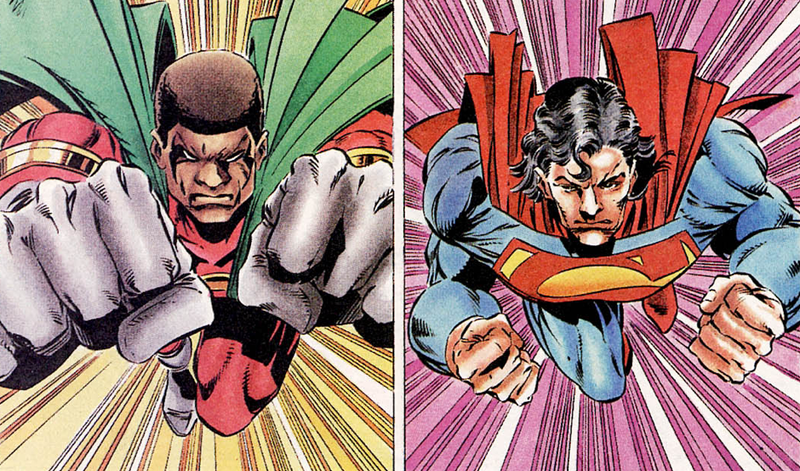

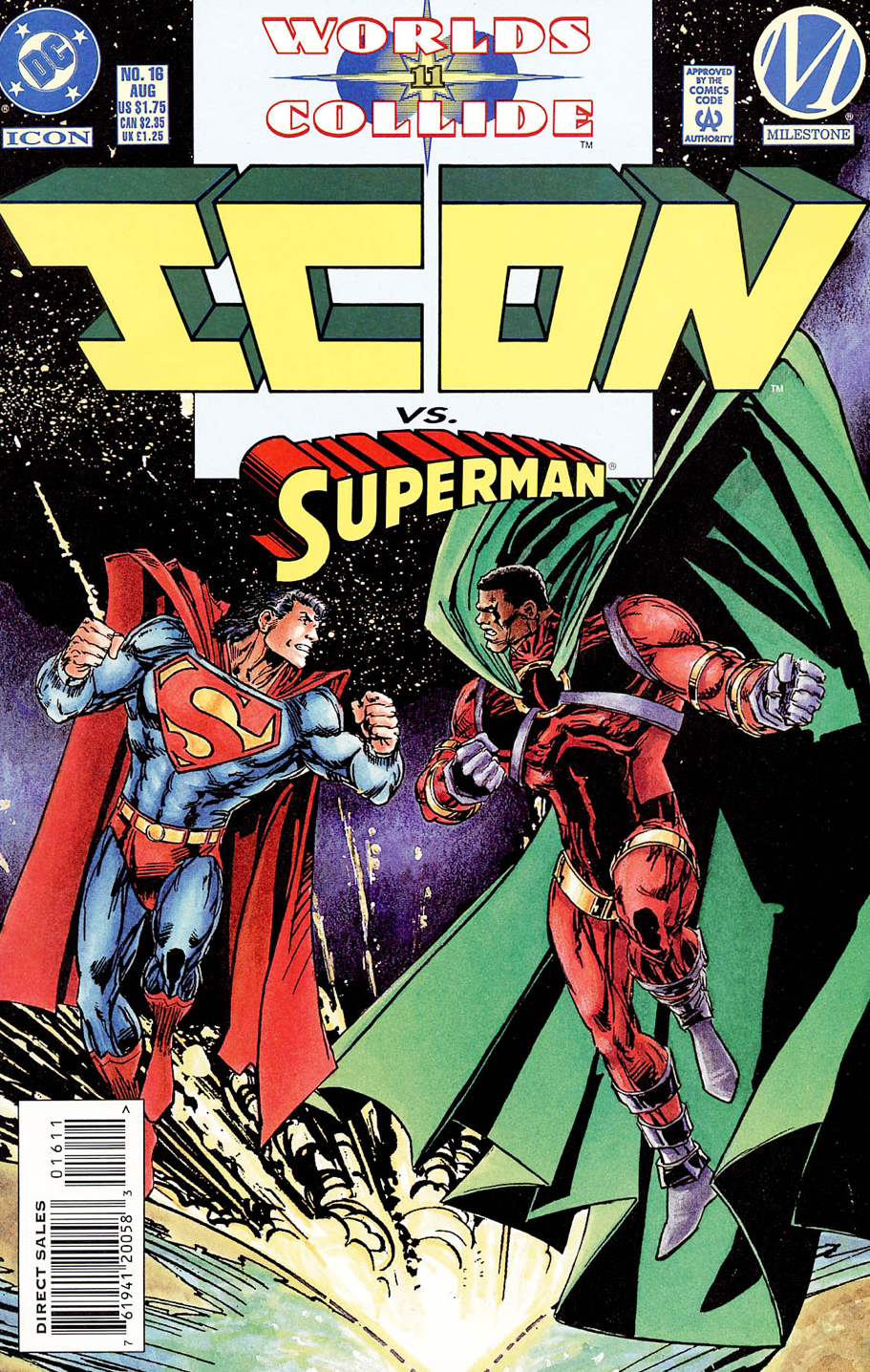

Great as that debut issue is, it’s Icon #16 that gave me life. It pit the title character against Superman, in a fight that the most powerful character in the Milestone universe couldn’t let the first superhero ever win. Underneath all the “good guys meet then throw down” pyrotechnics was a powerful meditation on how both marginalizers and the marginalized lose in American society.

The issue was part of the Worlds Collide crossover, which had characters from Milestone’s parallel universe meet various members of the Superman family of comics. The event revolved around a being named Rift, the cosmically empowered gestalt of a man who existed in both realities.

Rift decides that only one universe can survive and, in Icon #16, he makes the Man of Steel and the Hero of Dakota battle on behalf of the cities they protect. McDuffie writes Rift as a deluded creation deity, musing over the origins of Superman...

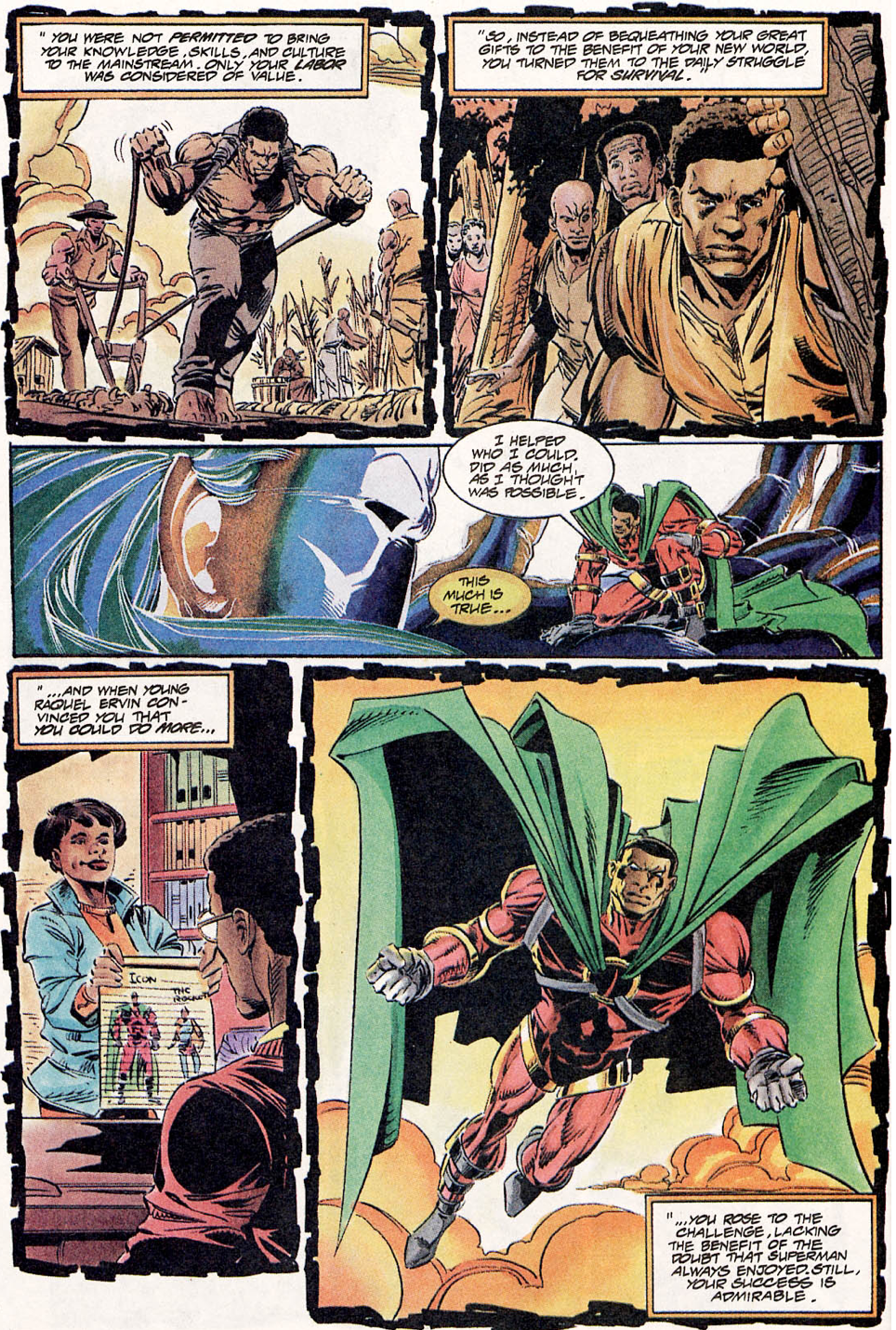

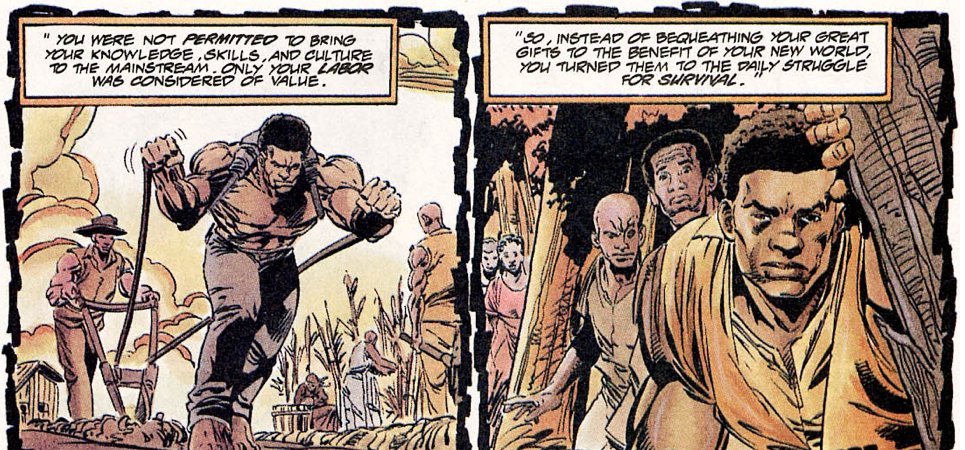

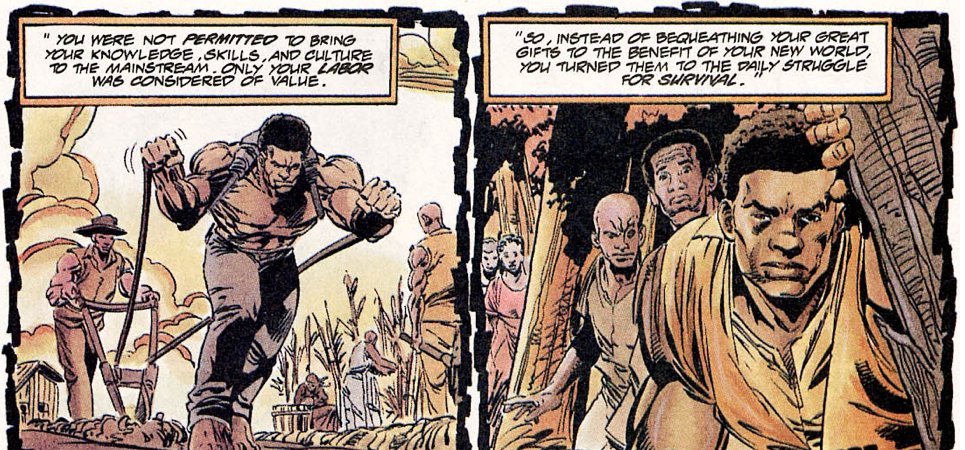

and Icon.

I’ve never forgotten the two sequences where Rift talks about how each hero was and wasn’t able to participate in society at large. The term “white privilege” wasn’t in popular usage, yet McDuffie uses the characters as metaphors for practices that have been around for centuries.

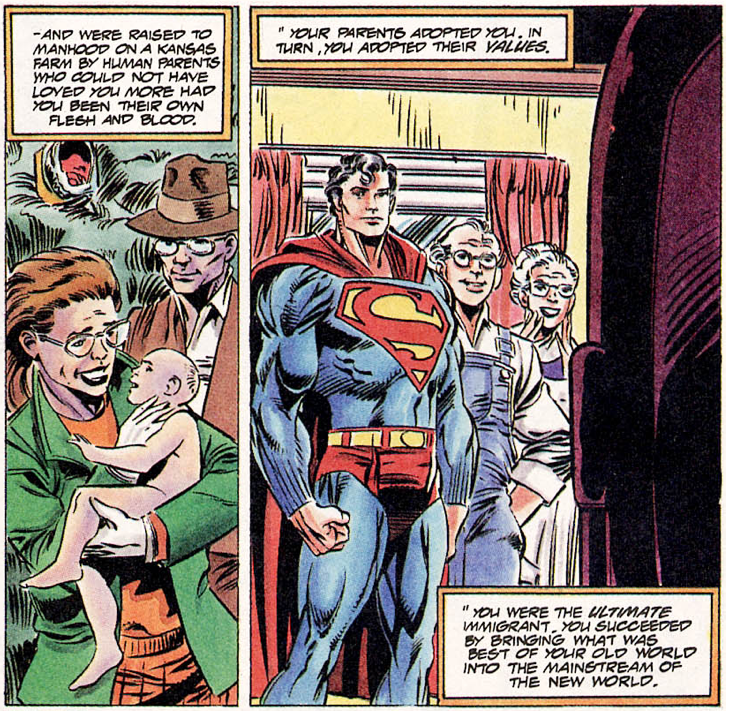

Superman is as alien as Icon. In fact, if you factor in the fact that Icon’s lived on Earth and in America for 150 years compared to Superman’s 30-something age, you could argue that Augustus Freeman is even more American than Clark Kent. But Kal-El enjoys a privilege that Icon doesn’t. The privilege is in being able to be thought of as fully human, to have your mind, body, wants, and needs be deemed of equal worth to those of the folks in power. The privilege is being able to be something more than three-fifths of a man, more than a tool, a foil or a means to an end.

When I interviewed McDuffie years ago, it was clear that he wanted readers to think about these themes:

“...I’m conscious of race whenever I’m writing, just as I’m conscious of class, religion, human psychology, politics—everything that makes up the human experience. I don’t think I can do a good job if I’m not paying attention to what’s meaningful to people, and in American culture, there isn’t anything that informs human interaction more than the idea of race.”

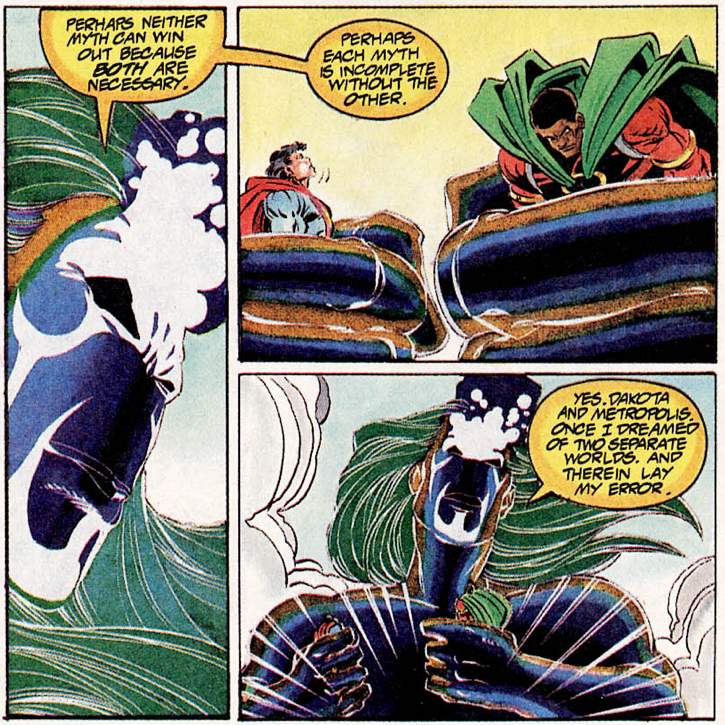

The end of Icon #16 has Rift realizing that there is essentially a stalemate between the two heroes because they’re connected symbiotically.

Icon #16 still stands out all these years later because it’s a work that does more than just comment on the need for black representation in mainstream superhero comics. It told America about itself via one of its biggest pop culture icons, hopefully making it consider all the black supermen and superwomen who were icons in lives that they may never have known about.

You’ve just read an entry in The Comics That Gave Me Life, an irregular series on the comics experiences that helped form my identity as a black nerd. There’s going to be more of these.

http://io9.gizmodo.com/the-superman-crossover-that-perfectly-explained-white-p-1785744977

Evan Narcisse

Yesterday 1:15pm

Filed to: ICON

72.0K

206108

An alien ship lands on Earth. Its occupant gets raised as human, hiding special abilities for fear of reprisal. But when the superpowered extraterrestrial becomes an adult, Truth, Justice and the American Way mean something very different. Because this strange visitor from another planet is black.

In 1993, a company called Milestone Media released a slate of comic-book series set in a multicultural universe where most of the heroes were black. With the exception of magazine editor Derek T. Dingle, Milestone’s founders—Christopher Priest, Michael Davis, Denys Cowan and Dwayne McDuffie—were all comics industry veterans who’d worked at Marvel and DC. Their collective desire to broaden the horizons of the medium’s characters and readership led them to come together and form Milestone. In the work that followed—published and distributed by DC Comics—the good guys and bad guys who battled in the in a fictional midwestern city called Dakota came from a multitude of ethnicities and walks of life. Characters in titles like Blood Syndicate, Heroes, and Deathwish were trailblazing efforts to conceptualize superheroes who were vessels for gender fluidity, loving same-sex relationships and socioeconomic tension. The subtext was never so heavy-handed as to take away from the well-crafted superhero yarns.

One of the first books that Milestone put out into the world was Icon, featuring a superstrong, cape-wearing flying hero with a young sidekick named Rocket. The series’ first issue introduces Icon’s secret identity of Augustus Freeman, a politically conservative African-American lawyer who’s been alive for more than 150 years.

Freeman is really an alien; he assumed human traits because his alien escape pod landed in the Deep South in 1839 and imprinted on the DNA of the field slave who became his adopted mother. If you need a modern-day reference for Augustus’ politics, think of someone like Herman Cain or Ben Carson. His bubble of complacency gets burst by a home invasion robbery, which he uses superhuman abilities to stop.

Raquel Ervin is one of the teens who tried to rob Freeman and, weeks after seeing him take to the sky, the Toni Morrison-wannabe decides that Augustus is going to be a superhero and she’s going to be his sidekick.

Co-created and written by McDuffie with art by M.D. “Doc” Bright, Iconrepresented an intentional shift from how the black heroes of previous decades were presented. Augustus Freeman wasn’t “street” and didn’t traffic in the jivey slang that characterized Luke Cage and other inner-city crimefighters.Icon #1 established one of the ongoing themes that series would touch, an exploration of what individuals and society owe each other. Raquel’s low-income realities don’t afford her the resources to make her dreams of becoming a writer come true while Augustus realizes that his upper-class elitism has cut him off from the world around him. He’s so out of touch that he thinks he can just fly down and offer his help to the cops dealing with a hostage situation.

He is, of course, very wrong.

I was in college when the Milestone line debuted, gobsmacked by the idea that there was going to be a whole universe of non-white superheroes. My excitement led me to do a project on the imprint for a cultural journalism class taught by the late, trailblazing pop music critic Ellen Willis. I remember a dismissive classmate sniffing at Icon, saying “So, he’s basically like a black Superman, then?” I didn’t always speak up a lot in college, the confidence that I have now in my faculties was still a long time coming. (I’m forever haunted by an a$$hole TA in a PoliSci class who ranted that “crack was a black drug” because it was years before I realized I could’ve retorted by asking him how crack got to the inner cities.) But when that classmate made his shallow remark about Icon, I said “No, he’s not a black Superman. And the book is about exactly why he can’t be.” I didn’t know I could say something like that until I actually said it. Something was waking up in me.

The late, legendary Dwayne McDuffie knew the possibilities of superhero comics. At their best, they can portray humanity in all its messy fullness, so that when our loftiest ideals win out over our worst aspects we’d feel that much closer to the heroes we read about. Augustus is uptight and judgmental, sheltered by his success. His turn towards understanding the generations that came after him is a journey back to empathy and community. He’s a Superman analog who isn’t already perfect; he’s perfecting himself.

Great as that debut issue is, it’s Icon #16 that gave me life. It pit the title character against Superman, in a fight that the most powerful character in the Milestone universe couldn’t let the first superhero ever win. Underneath all the “good guys meet then throw down” pyrotechnics was a powerful meditation on how both marginalizers and the marginalized lose in American society.

The issue was part of the Worlds Collide crossover, which had characters from Milestone’s parallel universe meet various members of the Superman family of comics. The event revolved around a being named Rift, the cosmically empowered gestalt of a man who existed in both realities.

Rift decides that only one universe can survive and, in Icon #16, he makes the Man of Steel and the Hero of Dakota battle on behalf of the cities they protect. McDuffie writes Rift as a deluded creation deity, musing over the origins of Superman...

and Icon.

I’ve never forgotten the two sequences where Rift talks about how each hero was and wasn’t able to participate in society at large. The term “white privilege” wasn’t in popular usage, yet McDuffie uses the characters as metaphors for practices that have been around for centuries.

Superman is as alien as Icon. In fact, if you factor in the fact that Icon’s lived on Earth and in America for 150 years compared to Superman’s 30-something age, you could argue that Augustus Freeman is even more American than Clark Kent. But Kal-El enjoys a privilege that Icon doesn’t. The privilege is in being able to be thought of as fully human, to have your mind, body, wants, and needs be deemed of equal worth to those of the folks in power. The privilege is being able to be something more than three-fifths of a man, more than a tool, a foil or a means to an end.

When I interviewed McDuffie years ago, it was clear that he wanted readers to think about these themes:

“...I’m conscious of race whenever I’m writing, just as I’m conscious of class, religion, human psychology, politics—everything that makes up the human experience. I don’t think I can do a good job if I’m not paying attention to what’s meaningful to people, and in American culture, there isn’t anything that informs human interaction more than the idea of race.”

The end of Icon #16 has Rift realizing that there is essentially a stalemate between the two heroes because they’re connected symbiotically.

Icon #16 still stands out all these years later because it’s a work that does more than just comment on the need for black representation in mainstream superhero comics. It told America about itself via one of its biggest pop culture icons, hopefully making it consider all the black supermen and superwomen who were icons in lives that they may never have known about.

You’ve just read an entry in The Comics That Gave Me Life, an irregular series on the comics experiences that helped form my identity as a black nerd. There’s going to be more of these.

http://io9.gizmodo.com/the-superman-crossover-that-perfectly-explained-white-p-1785744977

This is ya'll hero. He sounds like Michael Jordan.

This is ya'll hero. He sounds like Michael Jordan. I am guessing you just looked at the pretty pictures as opposed to reading the article. It says he starts of flawed and gradually works his way to perfecting himself. You know something commonly done in literature called character development.

I am guessing you just looked at the pretty pictures as opposed to reading the article. It says he starts of flawed and gradually works his way to perfecting himself. You know something commonly done in literature called character development.