UncleTomFord15

Veteran

There isn’t much known about Allen Brooks, the 65-year-old black man lynched in broad daylight in downtown Dallas on March 3, 1910. But what we do know is that 5,000 people gathered to watch him die.

And it’s likely we’ll never learn much more about Brooks: His life was cut short before he had an opportunity to receive due process under the law, to give his side of the story. Newspaper accounts of his torture and death — and decades later, projects to acknowledge Brooks’s humanity — have shed some light on both the circumstances of his death and the climate of early 20th-century Dallas, then a fast developing city with a population that had swelled to 92,000.

It all began on Feb. 27, 1910 when Brooks was found in the loft of his white employer’s barn with the family’s two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Mary Ethel Beuvens. She’d been missing for nearly four hours. After a doctor examined both Brooks and the girl, he was charged with attempted rape.

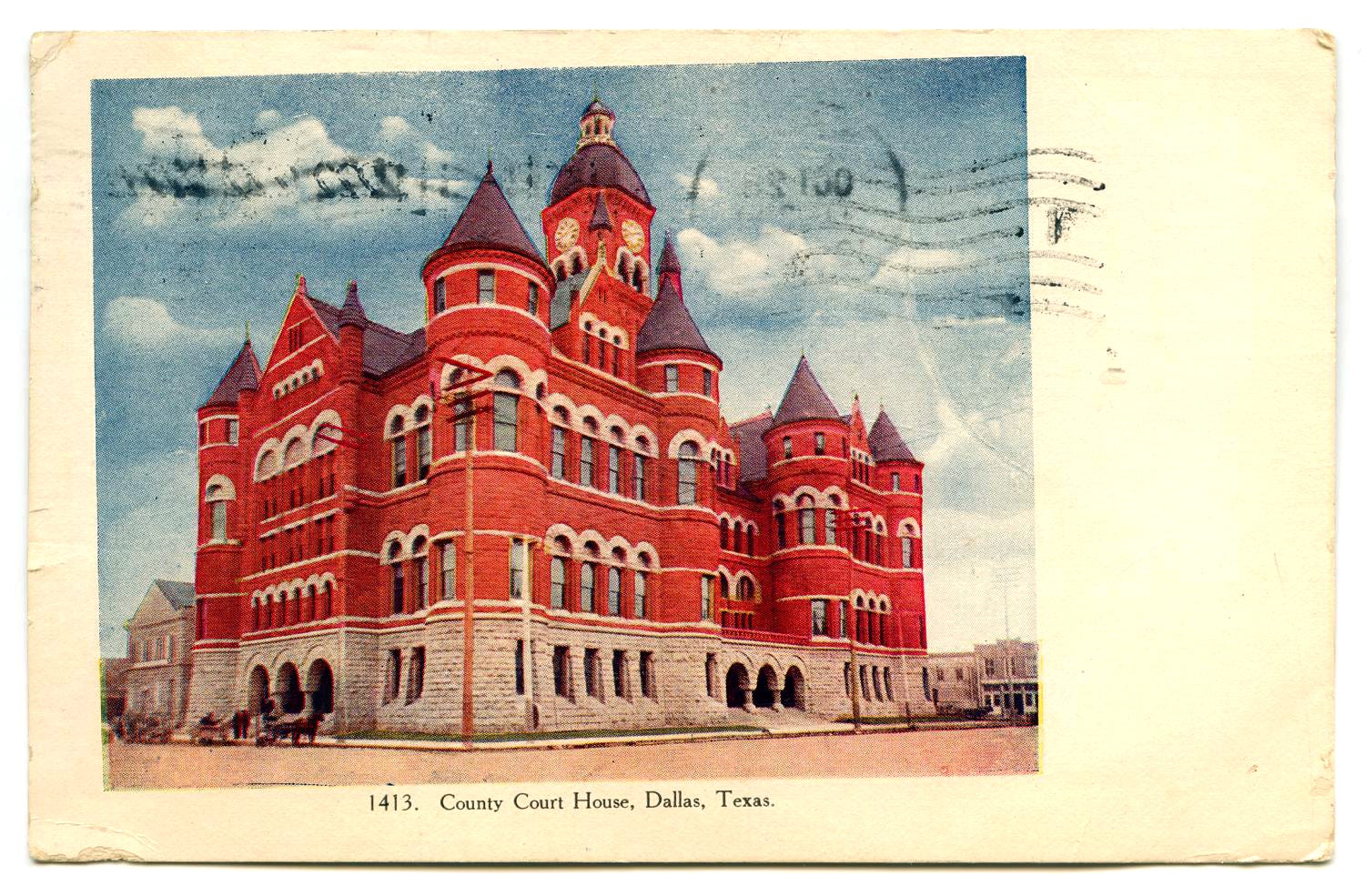

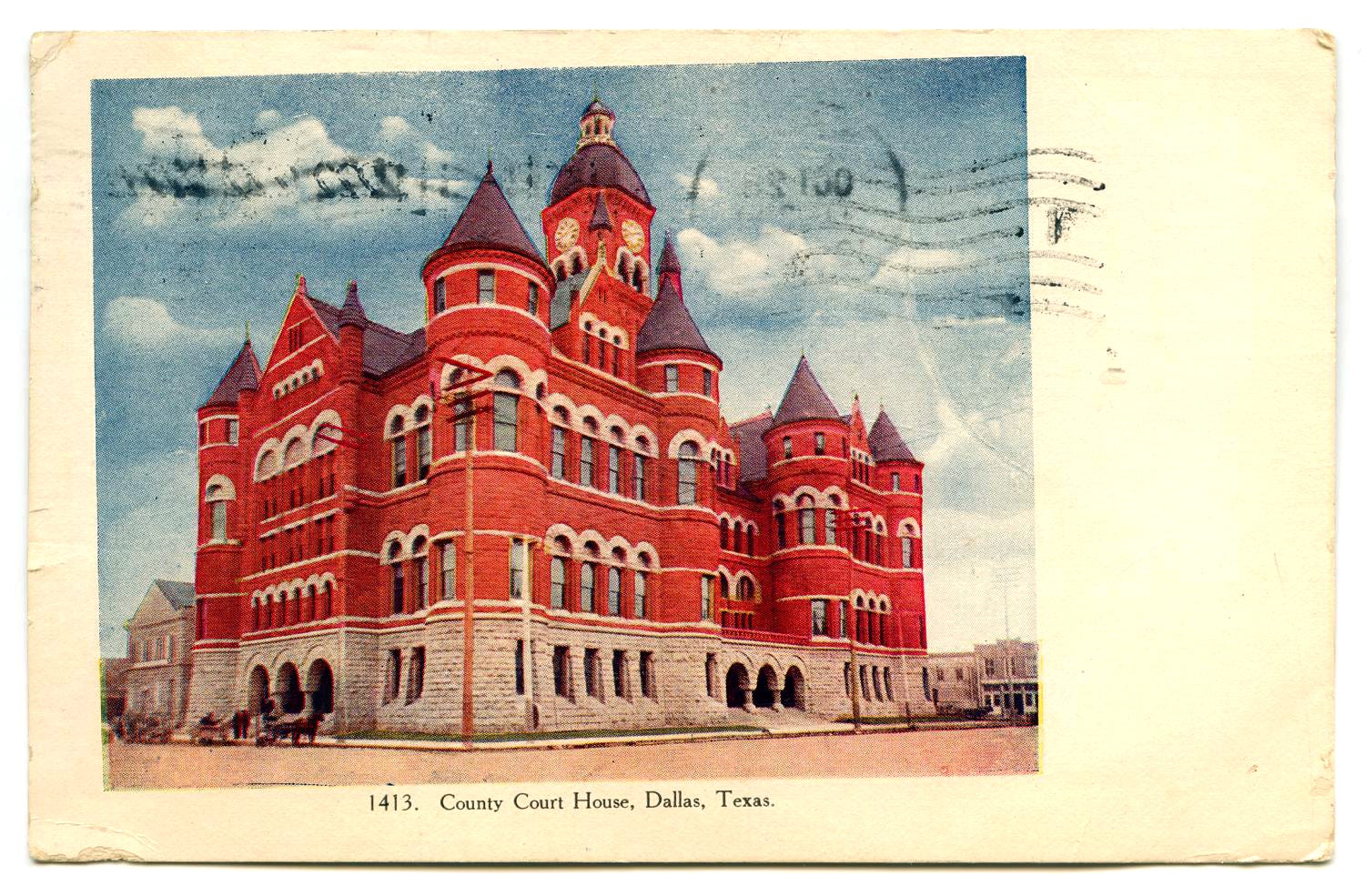

Over the next few days, Sheriff A.L. Ledbetter hid Brooks in area jails to protect him from vigilante violence, but that safety ended abruptly on the morning of his arraignment at the Dallas County Courthouse (which is now site of the Old Red Museum of Dallas County History and Culture). Hundreds of white men had been gathering outside seething for the chance to handle Brooks.

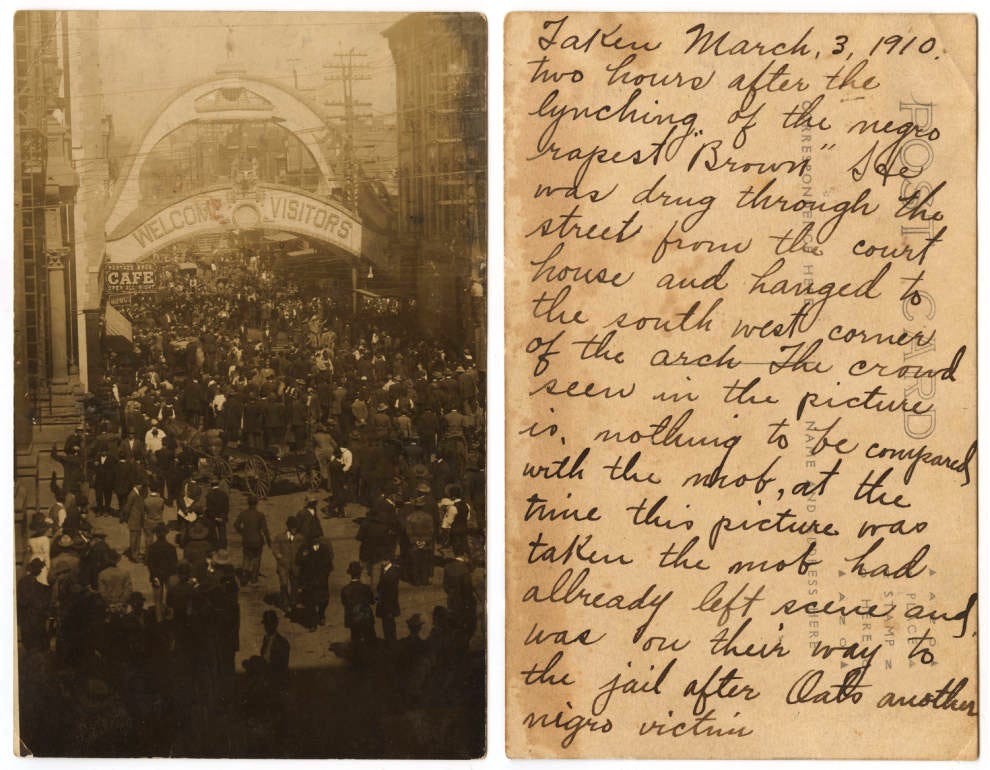

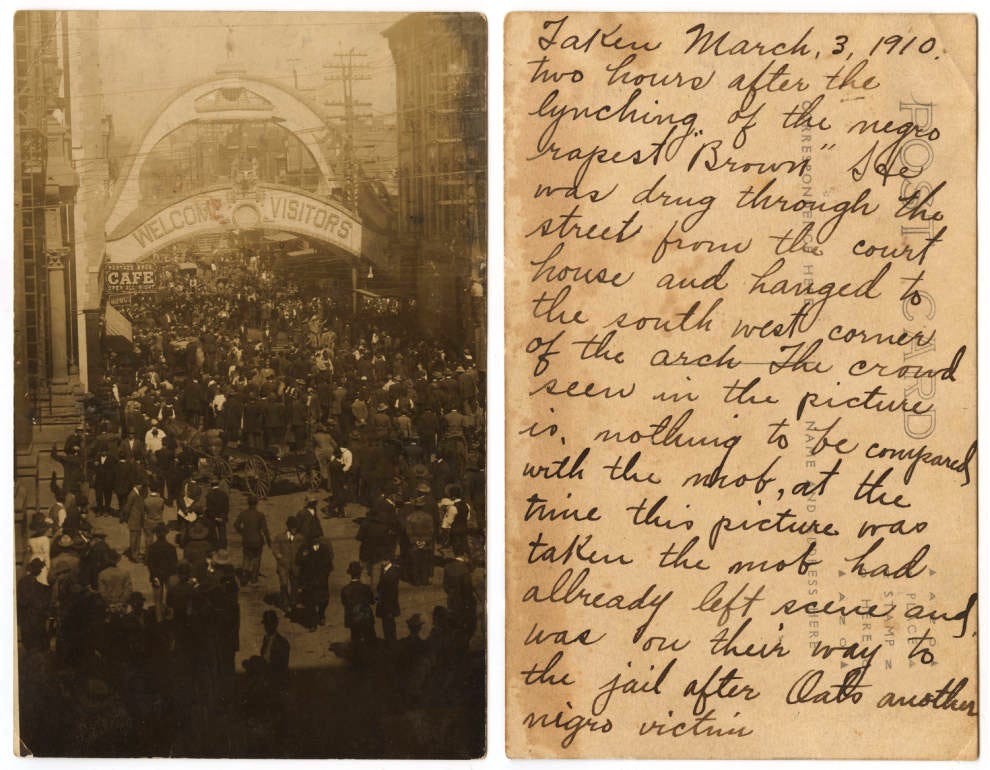

Another postcard shows crowds lingering in downtown Dallas, at the corner of Main and Akard, two hours after the lynching of Allen Brooks on March 3, 1910. (George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection via Southern Methodist University)

In that era of racial terror, too many black people accused of crimes were dealt with almost immediately by angry mobs.

Despite the pressure, that morning, Brooks’s attorneys asked for more time to gather witnesses. Judge Robert Seay granted just an hour. As the clock ticked, the crowd outside continued to grow in the thousands to witness Brooks’s fate as if it were a sporting event.

Suddenly, a mob burst into the courtroom, bulldozing the sheriff and his deputies. They grabbed Brooks from the jury room and pushed him headfirst out of a second-story window. Some believed he died then, but regardless, that didn’t stop the mob from defiling Brooks’s body. He was stabbed, beaten, and stomped in the head.

As a court document put it, “While the attorneys were preparing the motion, a mob entered the courtroom and killed the defendant. Cause dismissed.”

With a rope tied around his neck, Brooks was dragged down the street about half a mile until the crowd reached a telephone pole under the Elks Arch — a gaudy three-story structure at the corner of Main and Akard Streets that welcomed visitors to Dallas with light bulbs, antlers, and a statue of an elk on top.

The lurid story was enough to make newspapers across the country, and ultimately the world. Several weeks after the lynching, the mob scene at the courthouse was described in the New Zealand paper Marlborough Express “Blood streamed from the faces of the policemen and deputies,” the account read. “Some of them were slightly crippled, their arms hanging to their sides, useless. It was soon apparent that the mob would win. Enraged men stood on each other’s shoulders and scaled the railing. Walking to the second floor, they waited until others from below joined them. Then, as if by magic, from single individuals whose only purpose seemed to be to look on, they formed into a one wedged mass like a flying football wedge.”

When they were done with Brooks, the mob was thirsty for more violence. According to other newspaper reports, they called for the lynching of two other black inmates Burrell Oates and Bubber Robinson. The two men were both charged with murder. But this time, officials were able to hide the men in a nearby town.

Men, women, and children routinely witnessed such executions and often took something from the victim’s body as a memento. And in fact, spectators took pieces of clothing and bits of the rope from Brooks’s body.

His lynching lives also on in a postcard, which is now a part of the project and book Without Sanctuary, by James Allen. On the back of the postcard, a witness wrote, “Well John — This is a token of a great day in Dallas, March 3, a Negro was hung for an assault of a three year old girl. I saw this on my noon hour. I was very much in the bunch. You can see the Negro hanging on the telephone pole.”

By 1908, sending these postcards through the mail was illegal but it didn’t stop an underground market for the souvenirs.

Brooks was on trial at the Dallas County Courthouse when he was abducted by a lynch mob and thrown from a second floor window. (Private Collection of Margay Welch via University of North Texas Libraries)

Although Judge Robert Seay, the sheriff, his deputies, and the attorneys involved didn’t condone vigilante justice, neither did they have any sympathy for Brooks.

A court-appointed lawyer representing Brooks lamented, “I regret very much that Judge Seay appointed me. No one in Dallas condemns the crime of the Negro who committed it any more than I do. If I am forced to represent this Negro in court I will do so under protest, and I will see the law is complied within so far as I am capable, and that is as far as I will go.”

Four days after the lynching, Judge Seay insisted Brooks “was guilty and deserved death.”

Brooks was buried in Freedmen’s Cemetery, located in the Freedmen’s Town area of North Dallas, an enclave established by freed slaves. But even in death, Brooks’s existence — along with those of thousands of others buried there — was at risk of being erased.

Black residents in North Dallas were pushed south over the next few decades as the city looked to move out devalued homes to make way for highways and re-develop the area. There was also an increase in Ku Klux Klan activity. Work on Central Expressway was completed in 1949, creating a wedge in the community’s commercial district. The graves at Freedmen’s Cemetery would be discovered during this process. By the 1990s, descendants of those buried there and other citizens rallied to ensure the city would excavate the graves and honor the dead with a memorial park.

While there is a display about the lynching at the Old Red Museum of Dallas County History and Culture, there is no marker recognizing the lynching at the intersection of Main and Akard, now the site of Pegasus Plaza Park.

The intersection of Main and Akard in downtown Dallas, c. 1908 (left) and present day (right). The former site of the Elks Arch still bears no marker recognizing the lynching of Allen Brooks. (Southern Methodist University and Google)

Christopher Dowdy, and administrator at Dallas’ Paul Quinn College, spent five years delving into Brooks’s death, while creating the website Dallas Untold. There, he describes how the horrid history attached to the Elks Arch conveniently disappeared over time. It was dismantled within a year of Brooks’s death, and according to Dowdy, not because of the lynching. He found that the City Plan and Improvement League thought the arch was simply ugly, and that work crews wanted to make way for a sewer system project. The structure’s steel frame was eventually re-erected at the city’s fairgrounds.

“Its removal is exactly consistent with a theme of white racism: the disposability of black men and women; their memories, their neighborhoods, their very bodies,” Dowdy writes. “When we connect the assembled archival evidence with the built environment, the injuries and erasures of this structural racist violence become legible in the Dallas landscape.”

Brooks’ death has been gaining attention in recent years, as it was included in a 2015 lynching report released by the Equal Justice Initiative. The infamous postcard of his lynching is also included in an exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

The Dallas-based Sankofa Coalition — a group looking to recognize and seek atonement for past injustices — has also shared the story and organized a silent march on the anniversary of Brooks’s death.

In downtown Dallas, a crowd of 5,000 watched this black man get lynched—and they took souvenirs

And it’s likely we’ll never learn much more about Brooks: His life was cut short before he had an opportunity to receive due process under the law, to give his side of the story. Newspaper accounts of his torture and death — and decades later, projects to acknowledge Brooks’s humanity — have shed some light on both the circumstances of his death and the climate of early 20th-century Dallas, then a fast developing city with a population that had swelled to 92,000.

It all began on Feb. 27, 1910 when Brooks was found in the loft of his white employer’s barn with the family’s two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Mary Ethel Beuvens. She’d been missing for nearly four hours. After a doctor examined both Brooks and the girl, he was charged with attempted rape.

Over the next few days, Sheriff A.L. Ledbetter hid Brooks in area jails to protect him from vigilante violence, but that safety ended abruptly on the morning of his arraignment at the Dallas County Courthouse (which is now site of the Old Red Museum of Dallas County History and Culture). Hundreds of white men had been gathering outside seething for the chance to handle Brooks.

Another postcard shows crowds lingering in downtown Dallas, at the corner of Main and Akard, two hours after the lynching of Allen Brooks on March 3, 1910. (George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection via Southern Methodist University)

In that era of racial terror, too many black people accused of crimes were dealt with almost immediately by angry mobs.

Despite the pressure, that morning, Brooks’s attorneys asked for more time to gather witnesses. Judge Robert Seay granted just an hour. As the clock ticked, the crowd outside continued to grow in the thousands to witness Brooks’s fate as if it were a sporting event.

Suddenly, a mob burst into the courtroom, bulldozing the sheriff and his deputies. They grabbed Brooks from the jury room and pushed him headfirst out of a second-story window. Some believed he died then, but regardless, that didn’t stop the mob from defiling Brooks’s body. He was stabbed, beaten, and stomped in the head.

As a court document put it, “While the attorneys were preparing the motion, a mob entered the courtroom and killed the defendant. Cause dismissed.”

With a rope tied around his neck, Brooks was dragged down the street about half a mile until the crowd reached a telephone pole under the Elks Arch — a gaudy three-story structure at the corner of Main and Akard Streets that welcomed visitors to Dallas with light bulbs, antlers, and a statue of an elk on top.

The lurid story was enough to make newspapers across the country, and ultimately the world. Several weeks after the lynching, the mob scene at the courthouse was described in the New Zealand paper Marlborough Express “Blood streamed from the faces of the policemen and deputies,” the account read. “Some of them were slightly crippled, their arms hanging to their sides, useless. It was soon apparent that the mob would win. Enraged men stood on each other’s shoulders and scaled the railing. Walking to the second floor, they waited until others from below joined them. Then, as if by magic, from single individuals whose only purpose seemed to be to look on, they formed into a one wedged mass like a flying football wedge.”

When they were done with Brooks, the mob was thirsty for more violence. According to other newspaper reports, they called for the lynching of two other black inmates Burrell Oates and Bubber Robinson. The two men were both charged with murder. But this time, officials were able to hide the men in a nearby town.

Men, women, and children routinely witnessed such executions and often took something from the victim’s body as a memento. And in fact, spectators took pieces of clothing and bits of the rope from Brooks’s body.

His lynching lives also on in a postcard, which is now a part of the project and book Without Sanctuary, by James Allen. On the back of the postcard, a witness wrote, “Well John — This is a token of a great day in Dallas, March 3, a Negro was hung for an assault of a three year old girl. I saw this on my noon hour. I was very much in the bunch. You can see the Negro hanging on the telephone pole.”

By 1908, sending these postcards through the mail was illegal but it didn’t stop an underground market for the souvenirs.

Brooks was on trial at the Dallas County Courthouse when he was abducted by a lynch mob and thrown from a second floor window. (Private Collection of Margay Welch via University of North Texas Libraries)

Although Judge Robert Seay, the sheriff, his deputies, and the attorneys involved didn’t condone vigilante justice, neither did they have any sympathy for Brooks.

A court-appointed lawyer representing Brooks lamented, “I regret very much that Judge Seay appointed me. No one in Dallas condemns the crime of the Negro who committed it any more than I do. If I am forced to represent this Negro in court I will do so under protest, and I will see the law is complied within so far as I am capable, and that is as far as I will go.”

Four days after the lynching, Judge Seay insisted Brooks “was guilty and deserved death.”

Brooks was buried in Freedmen’s Cemetery, located in the Freedmen’s Town area of North Dallas, an enclave established by freed slaves. But even in death, Brooks’s existence — along with those of thousands of others buried there — was at risk of being erased.

Black residents in North Dallas were pushed south over the next few decades as the city looked to move out devalued homes to make way for highways and re-develop the area. There was also an increase in Ku Klux Klan activity. Work on Central Expressway was completed in 1949, creating a wedge in the community’s commercial district. The graves at Freedmen’s Cemetery would be discovered during this process. By the 1990s, descendants of those buried there and other citizens rallied to ensure the city would excavate the graves and honor the dead with a memorial park.

While there is a display about the lynching at the Old Red Museum of Dallas County History and Culture, there is no marker recognizing the lynching at the intersection of Main and Akard, now the site of Pegasus Plaza Park.

The intersection of Main and Akard in downtown Dallas, c. 1908 (left) and present day (right). The former site of the Elks Arch still bears no marker recognizing the lynching of Allen Brooks. (Southern Methodist University and Google)

Christopher Dowdy, and administrator at Dallas’ Paul Quinn College, spent five years delving into Brooks’s death, while creating the website Dallas Untold. There, he describes how the horrid history attached to the Elks Arch conveniently disappeared over time. It was dismantled within a year of Brooks’s death, and according to Dowdy, not because of the lynching. He found that the City Plan and Improvement League thought the arch was simply ugly, and that work crews wanted to make way for a sewer system project. The structure’s steel frame was eventually re-erected at the city’s fairgrounds.

“Its removal is exactly consistent with a theme of white racism: the disposability of black men and women; their memories, their neighborhoods, their very bodies,” Dowdy writes. “When we connect the assembled archival evidence with the built environment, the injuries and erasures of this structural racist violence become legible in the Dallas landscape.”

Brooks’ death has been gaining attention in recent years, as it was included in a 2015 lynching report released by the Equal Justice Initiative. The infamous postcard of his lynching is also included in an exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

The Dallas-based Sankofa Coalition — a group looking to recognize and seek atonement for past injustices — has also shared the story and organized a silent march on the anniversary of Brooks’s death.

In downtown Dallas, a crowd of 5,000 watched this black man get lynched—and they took souvenirs